We are now well past the corona crisis of 2020, and most of the restrictions around the world have been repealed or loosened. However, the long-term consequences of arbitrary and destructive corona policies are still with us—in fact, we are now in the middle of the inevitable economic crisis.

Proclaiming the great crash and economic crisis of 2022 is at this point not especially prescient or insightful, as commentators have been predicting it for months. The cause is still somewhat obscure, as financial and economic journalism still focuses on whatever the Federal Reserve announces. But the importance of the Fed’s moves is greatly exaggerated. The Fed cannot set interest rates at will; it cannot generate a boom or a recession at will. It can only print money and create the illusion of greater prosperity, but ultimately, reality reasserts itself.

The real driver of the present crisis is monetary inflation. Back in 2020, I (along with many others) pointed out the role of inflationary monetary policy in the corona crisis. While consumer price inflation is now the most apparent consequence, the real damage occurred in the capital structure of the economy. This is the cause of the present crisis.

A Business Cycle, of Sorts

While to most people the most obvious consequence of the corona inflation was the transfer payments they received from the government, the real action occurred in the business sector. Through various schemes, newly created money was channeled to the productive sector from the Fed via the Treasury. The result was a classic business cycle of unsustainable expansion ending in inevitable depression.

The immediate effect of the inflow of easy money was twofold. First, it hid some of the economic distortions that lockdowns and other restrictions caused. Since they received government funds to make up for lost revenue and to cover higher costs, businessmen maintained production lines that really should have been shut down or altered in some way due to lockdowns. Second, easy money induced capitalists to make new, unsound investments, as they thought the extra money meant greater capital availability.

These investments were unsound not because the government quickly turned off the money spigot again: they were unsound because the real resources were not there; people had not saved more to make them available. The supply of complementary factors of production had not increased, or not as much as suggested by the increase in money available for investment. As the businesses expanded and increased demand for these complementary factors, their prices therefore rose. To keep the boom going, businesses have started to borrow more money in the market, driving up interest rates. But there is no cheap credit to be had at this point, since there haven’t been additional infusions of cheap money since the initial inflation of 2020, so interest rates are quickly rising. This is the real explanation of the inversion of the yield curve: businesses are scrambling for funding as they find themselves in a liquidity shortage, since their input prices are rising above their revenues. It’s not the market front-running the Federal Reserve or any other fancy expectations-based cause: interest rates rise because businesses are short on capital.

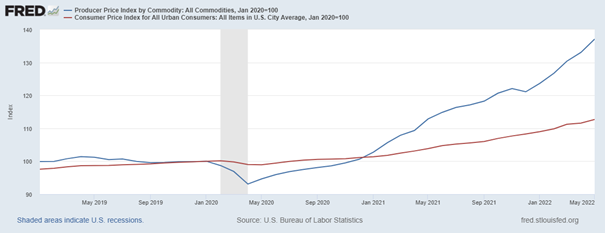

The following chart shows the increase in producer prices compared to consumer prices—an increase of almost 40 percent since the beginning of 2020 is clearly unsustainable. That consumer prices have not increased as much is a clear indication that we’re dealing with a business boom and that businesses can’t expect future revenues that will cover their elevated costs. Nor are we simply seeing oil price increases due to disruptions in supply. Oil and energy commodities complement virtually all production processes, so inflation-induced investment will lead to an early rise in oil and energy prices.

Figure 1: Producer and Consumer Price Indices, January 2019–May 2022

Eventually, interest rates will be bid too high, and businessmen will have to abandon their investments. Many will throw inventories on the market at almost any price to fund their liabilities, cut back their workforces, and likely go bankrupt. This appears to be happening already, as CNBC is reporting many layoffs in tech companies.

A likely consequence of this bust will be a banking crisis: as the share of nonperforming loans increases, bank revenues will dry up, and banks may find themselves unable to meet their own obligations. A crisis could develop, leading to what has been called “secondary deflation”: the contraction of the money supply as deposits in bankrupt banks simply evaporate. While that is a consummation devoutly to be wished, it is unlikely, to put it mildly, that the Federal Reserve will let things get to that point. This neatly brings us to a central question: What is the central bank doing right now?

The Contractionary Fed

Surprising as it sounds, the Fed really is pursuing a tightening policy. Not necessarily the one they officially announced—they are not, in fact, reducing their balance sheet, but an extremely tight policy nonetheless.

It is worth pointing out that the Fed is really a one-trick pony: all it can do is create money, either directly or indirectly by giving banks the reserves necessary for bank credit expansion. All the stuff about setting interest rates is secondary, if not irrelevant: the market always and everywhere sets interest rates. Central banks can only influence interest rates by, you guessed it, printing money.

Figure 2: M2 (billions of dollars), January 2019–April 2022

While the Fed was very inflationary back in 2020 as figures 2 and 3 show, it has since reversed course and become not only conservative, but outright contractionary. That is, not only has the growth rate slowed down, but there was a real, if small, fall in the quantity of money in early 2022.

Figure 3: M2 (percent change), January 2019–April 2022

This contraction is not immediately evident if we only look at the Fed’s overall balance sheet, because since March 2021, the Fed has aggressively increased the amount of reverse repurchase agreements (reverse repos) they hold (or owe, technically). In a reverse repo transaction, the Fed temporarily sells a bond to a bank (just as they temporarily buy a bond from a bank in a repo transaction). This sucks reserves from the system, just as repos add reserves to the system. From virtually zero in March 2021, the amount of reverse repos has increased to $2,421.6 billion as of June 15, reducing the amount of available reserves by the same amount. The Fed balance sheet has not shrunk due to simple accounting: the bond underlying the repo transaction is still recorded on the Fed balance sheet. Banks, meanwhile, benefit from this transaction even though their reserves are temporarily reduced, earning a practically risk-free 0.8 percent (the Fed increased the award rate on reverse repos to 1.55 percent on June 15 and will likely increase it in the near future as the market rate keeps rising).

Figure 4: Reverse Repurchase Agreements, March 2021–June 2022

Whatever this is, it’s not a policy that will feed inflation—in fact, inflation really will be transitory if the Fed continues its present policy. This is somewhat ironic, as the Fed has increased its holdings of inflation-indexed bonds, suggesting its economists themselves do not believe the transitory narrative. Of course, it’s possible that the Fed may simply be gearing up for the next round of inflationary policy.

What is certain is that the Fed is now neutralizing its previous inflation. The great 2020 inflation went first to the US Treasury account at the Fed and then to the government’s favored clients. As the government drew down its account, money went to the banks and was deposited at the Fed as reserves. At this point, the inflation could have accelerated. The banks were already flush with reserves and could have extended credit on top of the tidal wave of additional reserves flowing into them. This would likely have happened as the market rate of interest started rising, if not earlier, but by sucking banks’ reserves out the Fed is limiting banks’ inflationary potential. Credit expansion is still possible, as the banks maintain a historically elevated reserves-deposits ratio of around 20 percent and have since 2020 been liberated from any kind of legal reserve requirement. But by reducing the reserves in the system, the Fed is effectively preventing this development. After peaking at over 23 percent, the reserve ratio has steadily declined since September 2021, hitting 19 percent in April, as shown in figure 5. Since reverse repo transactions have continued in May and June, the monetary contraction seen in the first quarter is likely ongoing, although we will have to wait for more recent money supply figures to confirm this.

Figure 5: Banks’ Reserve Ratio, May 2020–April 2022

What Happens Now?

Whatever happens next, one thing is clear: the crisis is already upon us. Stock market declines and financial market chaos are really epiphenomena, headline capturing though they may be. The damage has already been done. And while I’ve here focused on the covid era, we were already heading for crisis in 2019—the coronavirus just provided an excuse for one last gigantic inflationary binge.

This means that it’s not simply the malinvestments of the last two years that needs to be cleared out—it’s the accumulated capital destruction of the last fifteen years that’s now becoming apparent. How much capital was wasted in tech start-ups that had no chance of ever turning a profit? As this piece in The Atlantic points out, enormous amounts of capital were poured into technology projects aimed at the hip urban millennial lifestyle—and now that they cannot cover operating costs with endless infusions of venture capital, prices are spiking and companies are laying off workers. The boom in construction is also at an end, as demand for housing is unlikely to remain elevated as mortgage rates rise.

In all likelihood, the Fed is not going to stay the course. Pressure from finance and from government is likely to force it back into inflation, but this inflation can’t prevent the bust. As Ludwig von Mises pointed out, you can’t paper over the economic crisis with yet another infusion of paper money; the crisis will play out, whatever the central bank decides to do. What the Fed can do is continue funding the government and bailing out the financial system when they come under pressure. Both will be very inflationary.

We should not celebrate the Fed for refraining from inflating the money supply at the moment—after all, its previous recklessness caused the problems to begin with—but let’s hope the Fed stays the course for now. The longer a new round of inflation is delayed, the more radical will the purge of malinvestment and clown-world finance be. High inflation is also possible, perhaps even more likely, given the political pressures. In that case, Weimar, here we come!

recession

depression

coronavirus

bonds

yield curve

monetary policy

fed

federal reserve

us treasury

mortgage rates

mortgages

recession

interest rates

commodities

oil

Read More