Government

The 19th Amendment at 100: Recapping the Brookings Gender Equality Series

The year 2020 will be remembered as one of the most consequential in generations: the COVID-19 pandemic devastated lives and livelihoods; millions protested across the country for racial justice following the murder of George Floyd; and the U.S. president

By Fred Dews

The year 2020 will be remembered as one of the most consequential in generations: the COVID-19 pandemic devastated lives and livelihoods; millions protested across the country for racial justice following the murder of George Floyd; and the U.S. presidential election gripped the body politic for months.

But 2020 was also the centennial of one of the most important civic events in American history—the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited denying the right to vote “on account of sex.” After 70 years of organizing and struggle by generations of women, the amendment’s ratification in August 1920 paved the way for millions of women to participate more fully in national elections and in the economic life of the nation. Although imperfectly implemented due to racism, sexism, and other factors, the expansion of the franchise opened new possibilities for women in their roles in the economy and society, and represented a victory in the long march toward gender equality.

To celebrate this milestone, but also to analyze the forces that have kept the United States from reaching true equality, the Brookings Institution launched “19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series,” a collection of 19 essays by Brookings scholars and other subject-matter experts that analyze how gender equality has evolved since the amendment’s passage and explore policy recommendations to end gender-based discrimination. Visit brookings.edu/19A to find links to individual essays. Read on to learn more about them and the themes they explore.

Looking back to inform the future

The history of the 19th Amendment’s passage, and expansion of women’s political equality generally, is a good place to start this review. In their essay, Janann Sherman and Paula Casey, educators based in Memphis, Tennessee, explore the ratification saga in the U.S. Congress, the states, and finally in Tennessee, whose legislature cast the deciding 36th ratification vote to enact the amendment. In their piece, Sherman and Casey explain that Tennessee was “a state divided” between supporters of ratification (Suffs) and opponents (Antis), the latter of which highlighted their two fears: surrender of state sovereignty and suffrage for Black women. After a week of hearings, debates, and delays in the Tennessee legislature during those hot August days, 24-year-old Harry Burn, the youngest member of the state assembly, cast the deciding vote for ratification, after receiving a note that morning from his mother who encouraged him to “vote for suffrage!”

By 1970, 50% of single women and 40% of married women were in the workforce

Historian Susan Ware, author of Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote, calls passage of the 19th Amendment an “incomplete victory.” Many women in the U.S. could already vote at the local level and women were engaged in political mobilization as early as the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, long before they could vote for U.S. president. “Celebrating the passage of the 19th Amendment,” Ware writes, “also slights the plight of African American voters, for whom the 19th Amendment was at most a hollow victory.” And, she adds, few Native American women gained the right to vote in 1920, and for other groups of women that right came even later.

Julia Gillard, former prime minister of Australia (the first and only woman PM of that country), writes of the “forgotten history” of women’s suffrage in South Australia, where women achieved political equality in 1894, a quarter of a century before American women. Women’s suffrage would be achieved nationwide in 1902. However, like in the United States, the newly won right of suffrage was not enjoyed by all women in Australia, especially not Aboriginal women who, along with Aboriginal men and Torres Strait Islander people, were excluded from federal elections until 1962. And even though women in Australia and worldwide have made great strides in political participation and representation, Gillard argues that “[a]cross the world, we must dismantle the continuing legal and social barriers that prevent women fully participating in economic, political, and community life.”

Women balancing work in the labor market and at home

“As we celebrate the centennial of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote,” writes Janet Yellen in her essay, “we should also celebrate the major strides women have made in the labor market. Their entry into paid work has been a major factor in America’s prosperity over the past century and a quarter.” Yellen, former chair of the Federal Reserve and a distinguished fellow in residence at Brookings when she authored this piece, and now President-elect Joe Biden’s nominee for Treasury secretary, offers a historical view of women in the U.S. labor force from the early 20th century to the present, documenting how changing mores around education and marriage have led to their increased participation in the labor force.

Women’s labor force participation has plateaued at just over 74%, less than men’s 93%

Labor force participation of women—both single and married—rose from the 1930s until by 1970 half of single women and 40 percent of married women were in the labor force. Despite this progress, however, prime working-age women’s labor force participation rate plateaued below that of men in the late 1990s, and is now at 76 percent. Yellen also explains that progress on narrowing the earnings gap between men and women has slowed, with full-time working women earning about 17 percent less than men. Further, women continue to face challenges combining careers and caregiving. Yellen calls for policies that benefit not only women, but all workers. “Pursuing such a strategy,” she says, “would be in keeping with the story of the rise in women’s involvement in the workforce, which has contributed not only to their own well-being but more broadly to the welfare and prosperity of our country.”

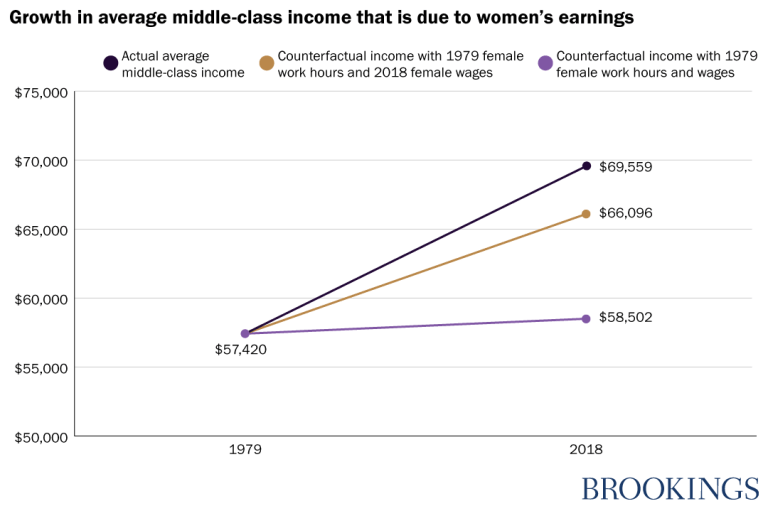

Continuing the theme of women balancing work and family, Isabel Sawhill and Katherine Guyot explore how women’s work boosts middle class incomes but creates a family time squeeze. Women’s labor earnings over the past few decades have contributed nearly all the gains in middle class family income (91 percent), but policies have failed to keep pace with these changes. As Sawhill and Guyot explain, the length of the standard work week, access to paid leave and childcare, and school hours have not adjusted to the changing composition of workers or the fact that women are “increasingly the chief breadwinners for their families”—over 40 percent of mothers are sole or primary earners for their families, they observe. While women entering the workforce and the social and political life of the nation post-19th Amendment must be celebrated, they argue, “The biggest remaining challenge is how to reconcile women’s new roles in the workforce with their continuing role in the family. Resolving this tension has implications not just for gender equity, but also for middle-class incomes and for the overall well-being of American families.”

New York University’s Paula England, Andrew Levine, and Emma Mishel also document the plateau in women’s labor force participation over the last two decades and offer insights into the state of the “gender revolution” in higher educational attainment, occupational choice, and pay equity. On some indicators, they note, progress has slowed or “completely stalled.” While women now earn more baccalaureate and doctoral degrees than men, “there are still many lucrative fields, for example engineering and computer science, that remain male bastions because fewer women than men major in those subjects.” Also, while women’s paid employment rose steadily from 1970 to 2000 (from 48 percent to three-quarters of women employed), their 2018 level stood at 73 percent.

These authors outline several policy changes to reinvigorate progress toward gender equality not only in the workplace, but also in the home.

Tina Tchen, president and CEO of TIME’S UP Foundation, which focuses on combatting sexual assault in the workplace, writes in her essay that passage of the 19th Amendment was just a start toward inclusion, as laws continued to keep women from full legal and economic participation. It was not until Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Tchen explains, that workplace protections against sex and race discrimination were outlawed. And still, Tchen notes that nearly 85 percent of women today report workplace sexual harassment. “Just as the 19th Amendment was a starting point for women to gain broader legal equity in society,” she says, “the laws against sexual harassment were only a starting point for the work necessary to extend real workplace protections and achieve workplace equity.”

Women on average earn 83% of what men do

In their essay, Nicole Bateman and Martha Ross expand on other research from Brookings scholars on the unequal impacts of the coronavirus on various groups, including women and people of color, due to the kinds of jobs they hold. Calling the COVID-19 pandemic a “major threat to the gains women have made in the workplace,” Bateman and Ross explain that “COVID-19 is hard on women because the U.S. economy is hard on women, and this virus excels at taking existing tensions and ratcheting them up.” Bateman and Ross describe how even before COVID-19 nearly half (46 percent) of working women—especially women of color—worked in low-wage jobs, faced more discrimination in the labor market, and lacked adequate childcare options, despite the fact that a quarter of working women have children under the age of 14 at home. Looking ahead, they argue that we cannot return to the pre-pandemic status quo: “A women’s place is in the family and the workforce, if they so choose. We can’t bounce back from the COVID-19 recession without interventions to support them in both roles. But we also need to recognize that although the pandemic created an acute and visible crisis, the lack of support for families and workers was a pre-existing condition.”

Adia Harvey Wingfield from Washington University in St. Louis addresses the racism and sexism still experienced in the workforce by women of color. While women generally earn around 80 cents for every dollar men earn, Black women earn 64 cents, and Latina women 54 cents. “As it was in the early 20th century,” Wingfield observes, “women of color continue to experience occupational and economic disadvantages that reflect the ways both race and gender affect their work experiences.” Factors such as stifled leadership opportunities, sexual harassment, and doubts about performance unrelated to job duties continue to impact women of color in professional settings. Calling for organizations to implement policies to become more equitable, Wingfield concludes that while “the U.S. has undoubtedly made some key social progressions since women finally achieved suffrage in 1920, we run the risk of hindering further gains if we fail to learn the lessons from that time.”

Women in government, the military, and politics

Many of the 19A Series essays focus on how women have participated—or have been thwarted from participating—in key sectors and policy accomplishments.

46% of all women work in low-wage jobs; 54% of Black women and 64% of Hispanic or Latina women do

Brookings scholar Michael O’Hanlon and Lori Robinson, a retired U.S. Air Force general and the first woman to lead a combatant American military command (USNORTHCOM), detail some of the challenges women have faced in the U.S. military. While today’s armed forces are more integrated than ever and women are no longer excluded from combat roles, O’Hanlon and Robinson note that women comprise only 16 percent of the armed forces, from 8 percent in the Marine Corps to 19 percent in the Air Force. Women’s representation in senior ranks is even lower, and women continue to face high rates of sexual assault. O’Hanlon and Robinson offer ideas for addressing the underrepresentation of women in the U.S. military, with particular attention to the barrier of having children while pursuing a military career.

In their essay, Nancy-Ann DeParle and Jeanne Lambrew document the essential role women played in passing and defending one of the most significant pieces of domestic legislation in generations: the Affordable Care Act of 2010. DeParle, who as a counselor to President Obama spearheaded efforts to enact the ACA, and Lambrew, who worked in both the Department of Health and Human Services and the White House to help implement and defend the act, explain how the law’s passage and implementation were “largely led by women.” As they point out: “The outsized role of women differentiates the ACA from other reform efforts. Few women appear in the narratives of the failed health initiatives of Presidents Truman, Nixon, and Trump.” And, they note, while First Lady Hillary Clinton led the health care reform effort at the start of the Clinton administration, women were not “disproportionately” represented in that effort. While noting that many men invested many years into passing the ACA, “women drove the policy development and the process day in and day out,” led implementation, and “were key at critical moments in its defense to this day.”

In her essay, Kathryn Dunn Tenpas of Brookings and the Governance Institute analyzes how many women have served in the White House as top presidential advisers, what she calls the “A Team” of the most influential decision-makers. For example, the percentage of women at this level was 5 percent during the Reagan administration, increased to 34 percent during the Obama administration, and dropped to 23 percent during the Trump administration.

While optimistic that the ranks of qualified women in the top tier of the White House will grow, she concludes that the “percentage of female ‘Decision Makers’ is astoundingly low, particularly in light of the broader gains that women have made in American politics over these many years.”

Richard Reeves broadens the analysis of women in politics to a comparison of the United States to its North American neighbors—Canada and Mexico. While only Canada has had a woman as national leader (Avril Campbell in 1993, and then only for six months), Reeves shows that the U.S. lags Canada and Mexico in terms of women in the legislature and in top ministerial positions (i.e., U.S. cabinet secretaries). And America’s poor comparison doesn’t stop on the continent’s shores: “Scoring poorly on all three metrics,” Reeves explains, “the U.S. falls into the bottom half of the global league table for gender equality in the political sphere, trailing behind, for example, the Philippines, India, South Korea, and the United Arab Emirates.”

And in the U.S. Congress, Reeves explains that while “rapid gains” have occurred in the representation of women, men continue to outnumber women 3 to 1. (This remains true even for the 117th Congress, despite a record number of women taking office.) Reeves notes that the “fight for equality began with politics, and specifically with the right to vote. After ten decades of significant social, cultural, and economic progress, the biggest challenge is once again in the political arena. Now, the need is for much greater representation of women in politics—including in the highest office in the land.”

A Black woman has to work 66 years to earn what a white man earns in 40

Andre Perry focuses his analysis on Black women in politics who, he says, are underrepresented at all levels of government, comprising only 2 percent of challengers to incumbents nationwide. While they have made significant gains, Black women continue to face both structural racism and sexism in their pursuit of political power. Writing in July, the month before Joe Biden chose Kamala Harris to be his running mate and months before the 2020 elections, Perry noted that “Black women carry the Black electorate in Black-majority cities,” and called for a Black woman vice presidential candidate this year. And yet, as Perry notes, “Without question, Black women are standard-bearers who transcend race and class. But we should be clear: The growing educational and cultural influence of Black women doesn’t equal protection” from physical violence and political underrepresentation.

Does gender equality lead to happiness and success for women?

Carol Graham, a leading analyst on the economics of well-being and happiness, explores the question, “Are women happier than men?” The answer, she says, is complicated. Women around the world generally report higher life satisfaction than men, but not in countries where gender rights are compromised. Women also report more daily stress. But even in wealthier countries where women started entering the labor force in large numbers decades ago, working women with children faced (and still face) significant challenges, as explored in the essays reviewed above. “While women’s rights have advanced a great deal in most wealthy countries,” Graham concludes, “there are still many poor women around the world whose lives—and well-being—will remain compromised for the foreseeable future. And, as the trajectory of those countries who have already improved equity in gender rights shows, the process is far from simple and does not end with legal changes alone.”

Each additional child reduces the average woman’s earnings by another 3%

Grace Enda and William Gale explore the status of women in retirement. Because women earn less than men on average over the course of a lifetime, it is more difficult to save for retirement. Women provide the majority of unpaid family caregiving, work in lower-wage occupations, receive unequal pay for similar work, and are more likely to care for aging parents, among other reasons why women earn less than men. Women even receive, on average, 80 percent of the Social Security benefits that men receive. “Exacerbating these differences,” they continue, “women are on average longer lived, more risk averse, less financially literate, and more likely to have greater caregiving responsibilities than men.” Enda and Gale conclude that “Fixing a retirement system that was not designed to accommodate women’s experiences will require significant changes, not just in retirement policy but in labor market practices and policies as well.”

Some of the essays in the 19A series examine women’s level of political participation; but what about women in leadership positions in other kinds of organizations around the world? Tuugi Chuluun and Kevin Young, professors at Loyola University Maryland and the University of Massachusetts Amherst, respectively, use a network analysis approach to understand women’s relative influence in elite networks. “Rather than simply counting the presence of leaders with different demographic characteristics,” they explain, “we use the dynamics of board ties across organizations to study interrelationships among these elites and analyze how an individual’s connections and position in the elite network are related to their gender as well as their race.” Their conclusion? “Despite significant steps toward a greater inclusion of women within leadership positions around the world, women leaders nevertheless remain relatively peripheral in network terms which may be confining their power and influence and hindering them from reaching their full potential. Hence, even at the commanding heights, women are still not fully integrated into the inner circle.”

Women’s rights abroad

Two essays explore contemporary challenges in gender equality worldwide. In her essay on advancing global gender equality through girls’ education, Christina Kwauk argues that “there is much stocktaking that the U.S. needs to do with regard to its role in advancing gender equality beyond our borders,” and in particular, “the U.S. government’s role in promoting girls’ education, a key pathway to achieving gender equality, must be stepped up significantly.” Kwauk explains why investment in girls’ education is “the world’s best investment” to enable girls and women to achieve more agency at home and in their communities. However, in many parts of the world, and especially in low-income countries, progress toward gender equality in education has plateaued and has even reversed due to COVID-19 responses while, as Kwauk explains, U.S. leadership and investment has diminished.

U.S. aid targeting gender equality was 7.9% of total aid by 2016, but 2.6% by 2018

Kwauk calls for a “feminist foreign policy” from Washington that “could help reinvigorate global progress toward gender equality. In another 100 years,” she says, “we should hopefully be able to look back and say that universal education for girls did for women and girls in the world what the enactment of the 19th Amendment did for gender equality in the U.S.”

Brookings President John R. Allen and scholar Vanda Felbab-Brown document the fate of women’s rights in Afghanistan. Their essay, published in September, comes at a time of ongoing developments on the ground in that country, as U.S. forces draw down and Taliban militants continue to attack Afghan forces. Allen and Felbab-Brown review the improvements achieved by some women in Afghanistan since the post-Taliban constitution of 2004, while noting that gains in access to education, health care, and representation in government have been distributed unevenly. As Afghanistan’s political order changes, however, Allen and Felbab-Brown write that “there are strong reasons to believe that the fate of Afghan women, particularly urban Afghan women from middle- and upper-class families who benefited by far the most from the post-2001 order, will worsen.” Their recommendations on what the U.S. and international community can do to preserve the gains made by Afghan women include setting minimal standards for women’s rights below which economic aid would not flow to a future government in Kabul, whether or not it is controlled by the Taliban.

—

For more content on the 19th Amendment and the progress of gender equality in the U.S. and around the word, watch video and download transcripts from an event on the centennial of the amendment, listen to a podcast with Brookings scholars and staff on what gender equality means to them, and listen to this podcast discussion among Brookings scholars on some of the key issues in women’s participation in the workforce and society, with attention to the gender impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

recession pandemic coronavirus covid-19 federal reserve white house congress trump recession south korea india mexico canadaInternational

This is the biggest money mistake you’re making during travel

A retail expert talks of some common money mistakes travelers make on their trips.

Travel is expensive. Despite the explosion of travel demand in the two years since the world opened up from the pandemic, survey after survey shows that financial reasons are the biggest factor keeping some from taking their desired trips.

Airfare, accommodation as well as food and entertainment during the trip have all outpaced inflation over the last four years.

Related: This is why we're still spending an insane amount of money on travel

But while there are multiple tricks and “travel hacks” for finding cheaper plane tickets and accommodation, the biggest financial mistake that leads to blown travel budgets is much smaller and more insidious.

This is what you should (and shouldn’t) spend your money on while abroad

“When it comes to traveling, it's hard to resist buying items so you can have a piece of that memory at home,” Kristen Gall, a retail expert who heads the financial planning section at points-back platform Rakuten, told Travel + Leisure in an interview. “However, it's important to remember that you don't need every souvenir that catches your eye.”

More Travel:

- A new travel term is taking over the internet (and reaching airlines and hotels)

- The 10 best airline stocks to buy now

- Airlines see a new kind of traveler at the front of the plane

According to Gall, souvenirs not only have a tendency to add up in price but also weight which can in turn require one to pay for extra weight or even another suitcase at the airport — over the last two months, airlines like Delta (DAL) , American Airlines (AAL) and JetBlue Airways (JBLU) have all followed each other in increasing baggage prices to in some cases as much as $60 for a first bag and $100 for a second one.

While such extras may not seem like a lot compared to the thousands one might have spent on the hotel and ticket, they all have what is sometimes known as a “coffee” or “takeout effect” in which small expenses can lead one to overspend by a large amount.

‘Save up for one special thing rather than a bunch of trinkets…’

“When traveling abroad, I recommend only purchasing items that you can't get back at home, or that are small enough to not impact your luggage weight,” Gall said. “If you’re set on bringing home a souvenir, save up for one special thing, rather than wasting your money on a bunch of trinkets you may not think twice about once you return home.”

Along with the immediate costs, there is also the risk of purchasing things that go to waste when returning home from an international vacation. Alcohol is subject to airlines’ liquid rules while certain types of foods, particularly meat and other animal products, can be confiscated by customs.

While one incident of losing an expensive bottle of liquor or cheese brought back from a country like France will often make travelers forever careful, those who travel internationally less frequently will often be unaware of specific rules and be forced to part with something they spent money on at the airport.

“It's important to keep in mind that you're going to have to travel back with everything you purchased,” Gall continued. “[…] Be careful when buying food or wine, as it may not make it through customs. Foods like chocolate are typically fine, but items like meat and produce are likely prohibited to come back into the country.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic franceSpread & Containment

As the pandemic turns four, here’s what we need to do for a healthier future

On the fourth anniversary of the pandemic, a public health researcher offers four principles for a healthier future.

Anniversaries are usually festive occasions, marked by celebration and joy. But there’ll be no popping of corks for this one.

March 11 2024 marks four years since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

Although no longer officially a public health emergency of international concern, the pandemic is still with us, and the virus is still causing serious harm.

Here are three priorities – three Cs – for a healthier future.

Clear guidance

Over the past four years, one of the biggest challenges people faced when trying to follow COVID rules was understanding them.

From a behavioural science perspective, one of the major themes of the last four years has been whether guidance was clear enough or whether people were receiving too many different and confusing messages – something colleagues and I called “alert fatigue”.

With colleagues, I conducted an evidence review of communication during COVID and found that the lack of clarity, as well as a lack of trust in those setting rules, were key barriers to adherence to measures like social distancing.

In future, whether it’s another COVID wave, or another virus or public health emergency, clear communication by trustworthy messengers is going to be key.

Combat complacency

As Maria van Kerkove, COVID technical lead for WHO, puts it there is no acceptable level of death from COVID. COVID complacency is setting in as we have moved out of the emergency phase of the pandemic. But is still much work to be done.

First, we still need to understand this virus better. Four years is not a long time to understand the longer-term effects of COVID. For example, evidence on how the virus affects the brain and cognitive functioning is in its infancy.

The extent, severity and possible treatment of long COVID is another priority that must not be forgotten – not least because it is still causing a lot of long-term sickness and absence.

Culture change

During the pandemic’s first few years, there was a question over how many of our new habits, from elbow bumping (remember that?) to remote working, were here to stay.

Turns out old habits die hard – and in most cases that’s not a bad thing – after all handshaking and hugging can be good for our health.

But there is some pandemic behaviour we could have kept, under certain conditions. I’m pretty sure most people don’t wear masks when they have respiratory symptoms, even though some health authorities, such as the NHS, recommend it.

Masks could still be thought of like umbrellas: we keep one handy for when we need it, for example, when visiting vulnerable people, especially during times when there’s a spike in COVID.

If masks hadn’t been so politicised as a symbol of conformity and oppression so early in the pandemic, then we might arguably have seen people in more countries adopting the behaviour in parts of east Asia, where people continue to wear masks or face coverings when they are sick to avoid spreading it to others.

Although the pandemic led to the growth of remote or hybrid working, presenteeism – going to work when sick – is still a major issue.

Encouraging parents to send children to school when they are unwell is unlikely to help public health, or attendance for that matter. For instance, although one child might recover quickly from a given virus, other children who might catch it from them might be ill for days.

Similarly, a culture of presenteeism that pressures workers to come in when ill is likely to backfire later on, helping infectious disease spread in workplaces.

At the most fundamental level, we need to do more to create a culture of equality. Some groups, especially the most economically deprived, fared much worse than others during the pandemic. Health inequalities have widened as a result. With ongoing pandemic impacts, for example, long COVID rates, also disproportionately affecting those from disadvantaged groups, health inequalities are likely to persist without significant action to address them.

Vaccine inequity is still a problem globally. At a national level, in some wealthier countries like the UK, those from more deprived backgrounds are going to be less able to afford private vaccines.

We may be out of the emergency phase of COVID, but the pandemic is not yet over. As we reflect on the past four years, working to provide clearer public health communication, avoiding COVID complacency and reducing health inequalities are all things that can help prepare for any future waves or, indeed, pandemics.

Simon Nicholas Williams has received funding from Senedd Cymru, Public Health Wales and the Wales Covid Evidence Centre for research on COVID-19, and has consulted for the World Health Organization. However, this article reflects the views of the author only, in his academic capacity at Swansea University, and no funding or organizational bodies were involved in the writing or content of this article.

vaccine treatment pandemic covid-19 spread social distancing uk world health organizationGovernment

The Grinch Who Stole Freedom

The Grinch Who Stole Freedom

Authored by Jeffrey A. Tucker via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Before President Joe Biden’s State of the…

Authored by Jeffrey A. Tucker via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Before President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address, the pundit class was predicting that he would deliver a message of unity and calm, if only to attract undecided voters to his side.

He did the opposite. The speech revealed a loud, cranky, angry, bitter side of the man that people don’t usually see. It seemed like the real Joe Biden I remember from the old days, full of venom, sarcasm, disdain, threats, and extreme partisanship.

The base might have loved it except that he made reference to an “illegal” alien, which is apparently a trigger word for the left. He failed their purity test.

The speech was stunning in its bile and bitterness. It’s beyond belief that he began with a pitch for more funds for the Ukraine war, which has killed 10,000 civilians and some 200,000 troops on both sides. It’s a bloody mess that could have been resolved early on but for U.S. tax funding of the conflict.

Despite the push from the higher ends of conservative commentary, average Republicans have turned hard against this war. The United States is in a fiscal crisis and every manner of domestic crisis, and the U.S. president opens his speech with a pitch to protect the border in Ukraine? It was completely bizarre, and lent some weight to the darkest conspiracies about why the Biden administration cares so much about this issue.

From there, he pivoted to wildly overblown rhetoric about the most hysterically exaggerated event of our times: the legendary Jan. 6 protests on Capitol Hill. Arrests for daring to protest the government on that day are growing.

The media and the Biden administration continue to describe it as the worst crisis since the War of the Roses, or something. It’s all a wild stretch, but it set the tone of the whole speech, complete with unrelenting attacks on former President Donald Trump. He would use the speech not to unite or make a pitch that he is president of the entire country but rather intensify his fundamental attack on everything America is supposed to be.

Hard to isolate the most alarming part, but one aspect really stood out to me. He glared directly at the Supreme Court Justices sitting there and threatened them with political power. He said that they were awful for getting rid of nationwide abortion rights and returning the issue to the states where it belongs, very obviously. But President Biden whipped up his base to exact some kind of retribution against the court.

Looking this up, we have a few historical examples of presidents criticizing the court but none to their faces in a State of the Union address. This comes two weeks after President Biden directly bragged about defying the Supreme Court over the issue of student loan forgiveness. The court said he could not do this on his own, but President Biden did it anyway.

Here we have an issue of civic decorum that you cannot legislate or legally codify. Essentially, under the U.S. system, the president has to agree to defer to the highest court in its rulings even if he doesn’t like them. President Biden is now aggressively defying the court and adding direct threats on top of that. In other words, this president is plunging us straight into lawlessness and dictatorship.

In the background here, you must understand, is the most important free speech case in U.S. history. The Supreme Court on March 18 will hear arguments over an injunction against President Biden’s administrative agencies as issued by the Fifth Circuit. The injunction would forbid government agencies from imposing themselves on media and social media companies to curate content and censor contrary opinions, either directly or indirectly through so-called “switchboarding.”

A ruling for the plaintiffs in the case would force the dismantling of a growing and massive industry that has come to be called the censorship-industrial complex. It involves dozens or even more than 100 government agencies, including quasi-intelligence agencies such as the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), which was set up only in 2018 but managed information flow, labor force designations, and absentee voting during the COVID-19 response.

A good ruling here will protect free speech or at least intend to. But, of course, the Biden administration could directly defy it. That seems to be where this administration is headed. It’s extremely dangerous.

A ruling for the defense and against the injunction would be a catastrophe. It would invite every government agency to exercise direct control over all media and social media in the country, effectively abolishing the First Amendment.

Close watchers of the court have no clear idea of how this will turn out. But watching President Biden glare at court members at the address, one does wonder. Did they sense the threats he was making against them? Will they stand up for the independence of the judicial branch?

Maybe his intimidation tactics will end up backfiring. After all, does the Supreme Court really think it is wise to license this administration with the power to control all information flows in the United States?

The deeper issue here is a pressing battle that is roiling American life today. It concerns the future and power of the administrative state versus the elected one. The Constitution contains no reference to a fourth branch of government, but that is what has been allowed to form and entrench itself, in complete violation of the Founders’ intentions. Only the Supreme Court can stop it, if they are brave enough to take it on.

If you haven’t figured it out yet, and surely you have, President Biden is nothing but a marionette of deep-state interests. He is there to pretend to be the people’s representative, but everything that he does is about entrenching the fourth branch of government, the permanent bureaucracy that goes on its merry way without any real civilian oversight.

We know this for a fact by virtue of one of his first acts as president, to repeal an executive order by President Trump that would have reclassified some (or many) federal employees as directly under the control of the elected president rather than have independent power. The elites in Washington absolutely panicked about President Trump’s executive order. They plotted to make sure that he didn’t get a second term, and quickly scratched that brilliant act by President Trump from the historical record.

This epic battle is the subtext behind nearly everything taking place in Washington today.

Aside from the vicious moment of directly attacking the Supreme Court, President Biden set himself up as some kind of economic central planner, promising to abolish hidden fees and bags of chips that weren’t full enough, as if he has the power to do this, which he does not. He was up there just muttering gibberish. If he is serious, he believes that the U.S. president has the power to dictate the prices of every candy bar and hotel room in the United States—an absolutely terrifying exercise of power that compares only to Stalin and Mao. And yet there he was promising to do just that.

Aside from demonizing the opposition, wildly exaggerating about Jan. 6, whipping up war frenzy, swearing to end climate change, which will make the “green energy” industry rich, threatening more taxes on business enterprise, promising to cure cancer (again!), and parading as the master of candy bar prices, what else did he do? Well, he took credit for the supposedly growing economy even as a vast number of Americans are deeply suffering from his awful policies.

It’s hard to imagine that this speech could be considered a success. The optics alone made him look like the Grinch who stole freedom, except the Grinch was far more articulate and clever. He’s a mean one, Mr. Biden.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex