Spread & Containment

States are choosing employers over workers by using COVID relief funds to pay off unemployment insurance debt: Policymakers shouldn’t be afraid to increase taxes on employers to improve unemployment insurance

Because the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing recession led to skyrocketing unemployment rates in early 2020, 23 states were forced to take out federal loans to continue paying out unemployment insurance (UI) benefits.

Because the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing recession led to skyrocketing unemployment rates in early 2020, 23 states were forced to take out federal loans to continue paying out unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. While interest was initially waived on these loans, these debts started to collect interest after Labor Day of 2021. In recent months, many states have chosen to use federal fiscal relief funds given to state and local governments by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 and the 2021 American Rescue Plan (ARP) to pay off accumulated UI trust fund debt.

This blog will detail why this is a poor use of federal recovery funds. Our main arguments are:

- Paying off UI trust fund debt accumulated in the past with fiscal relief funds means that these funds are not being used to support current investment or employment,

- Several key areas of state and local government investment have been deprived of funding for over a decade—using ARP relief funds to make up for this past investment deficit would spread the benefits of the fiscal aid much more broadly.

- State and local government employment remains steeply depressed from the COVID-19 economic shock. Restoring these jobs—and the full value of services these workers provided—should be a much higher priority for these governments than paying off UI debt.

- Paying down accumulated trust fund debts should be done by collecting more revenues from the employer payroll taxes earmarked for the UI system. These taxes have been kept far too low for too long and the result has been a dysfunctional UI system in many states.

Background

The expanded UI programs created in the CARES Act were crucial in providing relief to millions of people and creating a foundation for economic recovery. With unemployment rates in April 2020 reaching levels unseen since the Great Depression, the new and expanded UI programs propped up the inadequate preexisting state UI system and kept millions afloat by boosting household income. After being continued (albeit at less-generous levels) by the American Rescue Plan (ARP) in March 2021, the last of the federal UI programs expired at the beginning of September this year. This expiration cut off 7.5 million benefit recipients instantly and is projected to lower annual incomes by $144 billion.

Besides the temporary continuation of the pandemic UI programs, the ARP also allocated $350 billion in federal fiscal relief to state and local governments. The stated aims of this tranche of relief was to help stimulate demand to boost economic recovery and to make up for past public investment deficits (i.e., to help “build back better”). While many states are using ARP funds to support employment and expanded investments in areas like access to justice, arts and tourism, broadband, education, housing, workforce development, and more, other states have used ARP funds for less-useful purposes.

Given the huge value provided to workers by a well-functioning UI system, earmarking ARP fiscal relief to UI trust funds may seem like a useful way to spend these funds. However, paying down past debts does not support current employment or investment—and this support will be crucial for state and local governments in the coming years.

Further, history clearly shows that using federal relief funds to pay down accumulated UI trust fund debts is primarily a way to avoid raising employer-side taxes that finance state UI systems. Eventually, if we want a robust UI system that protects workers, we need to collect more money from employers through UI taxes—and doing it now is a much better way to pay down trust fund debts accumulated in the past 18 months than using federal relief funds.

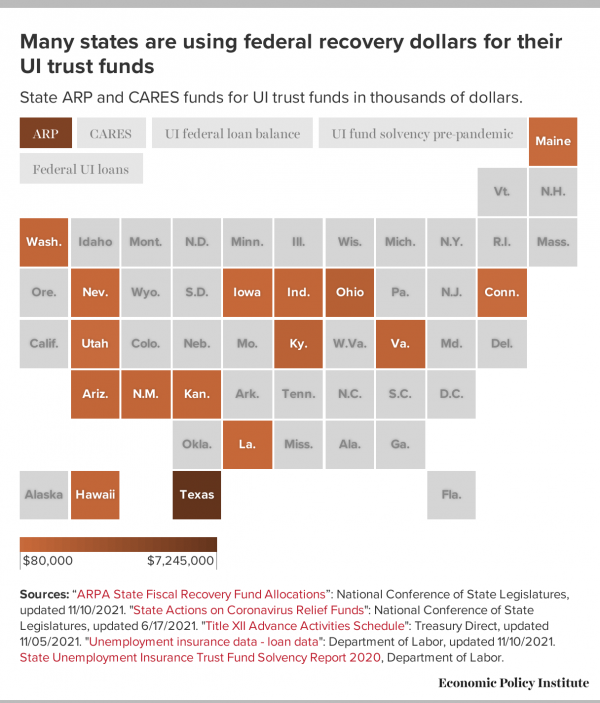

So far, 16 states (shown below) have collectively allocated $15.7 billion of ARP dollars toward their state UI trust funds. This comes after 23 states already used CARES Act funding to supplement their UI trust funds.

If a healthy UI system is a progressive good, why isn’t paying down accumulated UI trust fund debt a progressive use of American Rescue Plan funds?

It has been repeatedly argued that our current compounding crises necessitate an equitable recovery, where funds should be centered on the needs of working people and people marginalized and subordinated in our society. Using ARP funds to temporarily boost UI generosity in the face of continued pandemic conditions, or to modernize state UI systems to allow benefits to be paid in a timely and fair way, or to make a down payment on structural UI reform to make the system more protective of jobless workers, would all be admirable uses of ARP fiscal relief. However, using these funds to pay down accumulated debt provides no help to today’s workers relying on UI, and is instead just an insurance policy against employers having to pay higher taxes to finance UI in coming years. Given that these taxes are trivially low in dozens of states, protecting employers from any rise is hence not a progressive priority.

Normally, UI is funded by a mixture of state and federal taxes levied on most employers, where employers pay a federal UI tax authorized by the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) and a state unemployment tax as determined by individual state law. The FUTA tax rate is 6.0% on the first $7,000 of wages each employee is paid. However, employers are offered a tax reduction of up to 5.4 percentage points off this FUTA rate for paying their taxes on time (employers in states that have outstanding federal loans often do not qualify for this FUTA reduction). This means that some employers pay a meager $42 per year per employee in FUTA taxes.

Although states can borrow from the federal Unemployment Trust Fund (UTF) if their state unemployment taxes do not cover current benefits, they must repay their debts within a few years, which they have historically done by increasing the state unemployment tax rate for employers. States often face shortfalls because state unemployment taxes are often very low and many employers pay very little to finance UI. In 2020, employers paid on average $267 per employee, a 4% decrease from 2019. Moreover, an astonishing 75% of employers paid no more than $0.50 per every $100 they paid in employee wages.

Given how low UI taxes are on employers, using ARP funds to pay down UI trust fund balances simply to avoid increasing today’s often-trivial employer contributions is not a high-value or equitable use of ARP fiscal relief. The allegedly onerous cost of UI taxes for employers, particularly on small businesses, is the primary reason given for diverting ARP funds to state UI funds. This claim clearly exaggerates the burden on employers and is particularly harmful for progressive reforms because adequate UI taxes are vital for creating a healthy UI system.

Lessons from the Great Recession

We only have to look back to the Great Recession to see workers being hurt from the reluctance to increase UI taxes, when states had to take on federal loans to pay unemployment insurance. Between 2007 and 2012, 36 states borrowed federal dollars to pay unemployment benefits, more than during any previous recession. The downturn, with its historically high unemployment levels for extended periods of time, pulled the rug from underneath highly ill-prepared state UI systems. In 2007, only 19 state UI systems had achieved financial solvency, compared to 37 before the 2000 recession.

Having incurred debt to cover benefits during the worst of the recession, many states took drastic steps to avoid increasing UI taxes to pay back federal loans, at the expense of workers and the long-run health of their UI systems. To refill their UI coffers more quickly, nine states reduced the length of their unemployment benefits package below 26 weeks while 14 states froze or reduced their maximum weekly unemployment benefits. The decision to cut UI during an economic recovery was unprecedented.

Tellingly, states that cut UI duration were not particularly better off in their trust fund solvency during the recession but did have histories of cutting safety net programs. Cutting UI duration caused unemployed workers to lose an average of $252 a week, while also undermining the macroeconomic benefits associated with strong UI benefits. States also lowered enrollment by reducing eligibility and adding additional barriers for UI applicants.

In 2017—eight years into the recovery—UI taxes were at their fourth lowest levels in the history of the UI system, and despite cruel and unprecedented cuts to benefits, aggregate trust fund balances were only half of what they had been in June 2000. State lawmakers’ unwillingness to place higher UI taxes on employers not only contributed to the ill-prepared state of UI before the Great Recession but also failed to adequately strengthen UI systems before the pandemic recession, all while making decisions that harmed workers and dragged down the recovery.

Better uses for American Rescue Plan funds

Using federal recovery funds to top up UI trust funds does not actually fix any of the well-documented, long-run problems with UI. The expanded UI programs created in the CARES Act propped up the inadequate preexisting state UI system with federal funds and kept millions afloat by boosting household income. The three federal pandemic UI programs were created to meet three very specific shortcomings in the existing UI architecture: eligibility (too few people were eligible, especially gig workers and independent contractors), duration (UI benefits didn’t last long enough), and generosity (the small benefit amount was barely enough to cover costs). If states really want to equitably use ARP funds on UI, they should spend the funds addressing these problems in their UI programs, as well as upgrading outdated UI technology and boosting administrative staffing capacity. Using ARP funds to pay down UI debts simply kicks the can down the road for redesigning these systems and ensuring they’re adequately financed.

Using ARP funds to pay down UI trust fund debt accrued in the past also takes away money that could be used in the present to support public employment and strengthen public goods and services. State and local government employment is still down almost a million jobs from before the pandemic, with the majority of those missing jobs in K-12 education. These funds could also be used to eliminate barriers to accessing both UI and other social services, and increase direct cash transfers. In the end, not only does direct spending on public services and aid to households offer financial relief and recovery, they have also been shown to have a stronger macroeconomic stimulus effect than aid to businesses like tax cuts. Using ARP funds on public services and people, rather than giving an employer tax cut through paying off UI funds, is good economics and the right thing to do.

In its role both as social insurance when people lose their jobs and as a macroeconomic stabilizer to boost aggregate demand, UI has never been more successful than during the 2020-2021 downturn. Compared to the 2007-2009 recession, UI as a share of personal income was four times as high in 2020-2021. Given its success and widespread usage, especially by workers previously excluded from the UI system, allowing these programs to expire with no replacement was a harmful decision.

Using critical ARP funds meant to stimulate the economy and foster longer-term economic growth in order to replenish UI trust funds is also a mistake. States shouldn’t be afraid to increase taxes on employers or simply have more employers pay the full existing tax rates in order to create sustainable UI systems. Workers deserve genuine social protection, including a robust unemployment insurance system.

recession economic shock depression unemployment pandemic coronavirus covid-19 economic recovery stimulus economic growth spread recession recovery unemployment stimulusSpread & Containment

The Coming Of The Police State In America

The Coming Of The Police State In America

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

The National Guard and the State Police are now…

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

The National Guard and the State Police are now patrolling the New York City subway system in an attempt to do something about the explosion of crime. As part of this, there are bag checks and new surveillance of all passengers. No legislation, no debate, just an edict from the mayor.

Many citizens who rely on this system for transportation might welcome this. It’s a city of strict gun control, and no one knows for sure if they have the right to defend themselves. Merchants have been harassed and even arrested for trying to stop looting and pillaging in their own shops.

The message has been sent: Only the police can do this job. Whether they do it or not is another matter.

Things on the subway system have gotten crazy. If you know it well, you can manage to travel safely, but visitors to the city who take the wrong train at the wrong time are taking grave risks.

In actual fact, it’s guaranteed that this will only end in confiscating knives and other things that people carry in order to protect themselves while leaving the actual criminals even more free to prey on citizens.

The law-abiding will suffer and the criminals will grow more numerous. It will not end well.

When you step back from the details, what we have is the dawning of a genuine police state in the United States. It only starts in New York City. Where is the Guard going to be deployed next? Anywhere is possible.

If the crime is bad enough, citizens will welcome it. It must have been this way in most times and places that when the police state arrives, the people cheer.

We will all have our own stories of how this came to be. Some might begin with the passage of the Patriot Act and the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security in 2001. Some will focus on gun control and the taking away of citizens’ rights to defend themselves.

My own version of events is closer in time. It began four years ago this month with lockdowns. That’s what shattered the capacity of civil society to function in the United States. Everything that has happened since follows like one domino tumbling after another.

It goes like this:

1) lockdown,

2) loss of moral compass and spreading of loneliness and nihilism,

3) rioting resulting from citizen frustration, 4) police absent because of ideological hectoring,

5) a rise in uncontrolled immigration/refugees,

6) an epidemic of ill health from substance abuse and otherwise,

7) businesses flee the city

8) cities fall into decay, and that results in

9) more surveillance and police state.

The 10th stage is the sacking of liberty and civilization itself.

It doesn’t fall out this way at every point in history, but this seems like a solid outline of what happened in this case. Four years is a very short period of time to see all of this unfold. But it is a fact that New York City was more-or-less civilized only four years ago. No one could have predicted that it would come to this so quickly.

But once the lockdowns happened, all bets were off. Here we had a policy that most directly trampled on all freedoms that we had taken for granted. Schools, businesses, and churches were slammed shut, with various levels of enforcement. The entire workforce was divided between essential and nonessential, and there was widespread confusion about who precisely was in charge of designating and enforcing this.

It felt like martial law at the time, as if all normal civilian law had been displaced by something else. That something had to do with public health, but there was clearly more going on, because suddenly our social media posts were censored and we were being asked to do things that made no sense, such as mask up for a virus that evaded mask protection and walk in only one direction in grocery aisles.

Vast amounts of the white-collar workforce stayed home—and their kids, too—until it became too much to bear. The city became a ghost town. Most U.S. cities were the same.

As the months of disaster rolled on, the captives were let out of their houses for the summer in order to protest racism but no other reason. As a way of excusing this, the same public health authorities said that racism was a virus as bad as COVID-19, so therefore it was permitted.

The protests had turned to riots in many cities, and the police were being defunded and discouraged to do anything about the problem. Citizens watched in horror as downtowns burned and drug-crazed freaks took over whole sections of cities. It was like every standard of decency had been zapped out of an entire swath of the population.

Meanwhile, large checks were arriving in people’s bank accounts, defying every normal economic expectation. How could people not be working and get their bank accounts more flush with cash than ever? There was a new law that didn’t even require that people pay rent. How weird was that? Even student loans didn’t need to be paid.

By the fall, recess from lockdown was over and everyone was told to go home again. But this time they had a job to do: They were supposed to vote. Not at the polling places, because going there would only spread germs, or so the media said. When the voting results finally came in, it was the absentee ballots that swung the election in favor of the opposition party that actually wanted more lockdowns and eventually pushed vaccine mandates on the whole population.

The new party in control took note of the large population movements out of cities and states that they controlled. This would have a large effect on voting patterns in the future. But they had a plan. They would open the borders to millions of people in the guise of caring for refugees. These new warm bodies would become voters in time and certainly count on the census when it came time to reapportion political power.

Meanwhile, the native population had begun to swim in ill health from substance abuse, widespread depression, and demoralization, plus vaccine injury. This increased dependency on the very institutions that had caused the problem in the first place: the medical/scientific establishment.

The rise of crime drove the small businesses out of the city. They had barely survived the lockdowns, but they certainly could not survive the crime epidemic. This undermined the tax base of the city and allowed the criminals to take further control.

The same cities became sanctuaries for the waves of migrants sacking the country, and partisan mayors actually used tax dollars to house these invaders in high-end hotels in the name of having compassion for the stranger. Citizens were pushed out to make way for rampaging migrant hordes, as incredible as this seems.

But with that, of course, crime rose ever further, inciting citizen anger and providing a pretext to bring in the police state in the form of the National Guard, now tasked with cracking down on crime in the transportation system.

What’s the next step? It’s probably already here: mass surveillance and censorship, plus ever-expanding police power. This will be accompanied by further population movements, as those with the means to do so flee the city and even the country and leave it for everyone else to suffer.

As I tell the story, all of this seems inevitable. It is not. It could have been stopped at any point. A wise and prudent political leadership could have admitted the error from the beginning and called on the country to rediscover freedom, decency, and the difference between right and wrong. But ego and pride stopped that from happening, and we are left with the consequences.

The government grows ever bigger and civil society ever less capable of managing itself in large urban centers. Disaster is unfolding in real time, mitigated only by a rising stock market and a financial system that has yet to fall apart completely.

Are we at the middle stages of total collapse, or at the point where the population and people in leadership positions wise up and decide to put an end to the downward slide? It’s hard to know. But this much we do know: There is a growing pocket of resistance out there that is fed up and refuses to sit by and watch this great country be sacked and taken over by everything it was set up to prevent.

Spread & Containment

Another beloved brewery files Chapter 11 bankruptcy

The beer industry has been devastated by covid, changing tastes, and maybe fallout from the Bud Light scandal.

Before the covid pandemic, craft beer was having a moment. Most cities had multiple breweries and taprooms with some having so many that people put together the brewery version of a pub crawl.

It was a period where beer snobbery ruled the day and it was not uncommon to hear bar patrons discuss the makeup of the beer the beer they were drinking. This boom period always seemed destined for failure, or at least a retraction as many markets seemed to have more craft breweries than they could support.

Related: Fast-food chain closes more stores after Chapter 11 bankruptcy

The pandemic, however, hastened that downfall. Many of these local and regional craft breweries counted on in-person sales to drive their business.

And while many had local and regional distribution, selling through a third party comes with much lower margins. Direct sales drove their business and the pandemic forced many breweries to shut down their taprooms during the period where social distancing rules were in effect.

During those months the breweries still had rent and employees to pay while little money was coming in. That led to a number of popular beermakers including San Francisco's nationally-known Anchor Brewing as well as many regional favorites including Chicago’s Metropolitan Brewing, New Jersey’s Flying Fish, Denver’s Joyride Brewing, Tampa’s Zydeco Brew Werks, and Cleveland’s Terrestrial Brewing filing bankruptcy.

Some of these brands hope to survive, but others, including Anchor Brewing, fell into Chapter 7 liquidation. Now, another domino has fallen as a popular regional brewery has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

Image source: Shutterstock

Covid is not the only reason for brewery bankruptcies

While covid deserves some of the blame for brewery failures, it's not the only reason why so many have filed for bankruptcy protection. Overall beer sales have fallen driven by younger people embracing non-alcoholic cocktails, and the rise in popularity of non-beer alcoholic offerings,

Beer sales have fallen to their lowest levels since 1999 and some industry analysts

"Sales declined by more than 5% in the first nine months of the year, dragged down not only by the backlash and boycotts against Anheuser-Busch-owned Bud Light but the changing habits of younger drinkers," according to data from Beer Marketer’s Insights published by the New York Post.

Bud Light parent Anheuser Busch InBev (BUD) faced massive boycotts after it partnered with transgender social media influencer Dylan Mulvaney. It was a very small partnership but it led to a right-wing backlash spurred on by Kid Rock, who posted a video on social media where he chastised the company before shooting up cases of Bud Light with an automatic weapon.

Another brewery files Chapter 11 bankruptcy

Gizmo Brew Works, which does business under the name Roth Brewing Company LLC, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on March 8. In its filing, the company checked the box that indicates that its debts are less than $7.5 million and it chooses to proceed under Subchapter V of Chapter 11.

"Both small business and subchapter V cases are treated differently than a traditional chapter 11 case primarily due to accelerated deadlines and the speed with which the plan is confirmed," USCourts.gov explained.

Roth Brewing/Gizmo Brew Works shared that it has 50-99 creditors and assets $100,000 and $500,000. The filing noted that the company does expect to have funds available for unsecured creditors.

The popular brewery operates three taprooms and sells its beer to go at those locations.

"Join us at Gizmo Brew Works Craft Brewery and Taprooms located in Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Find us for entertainment, live music, food trucks, beer specials, and most importantly, great-tasting craft beer by Gizmo Brew Works," the company shared on its website.

The company estimates that it has between $1 and $10 million in liabilities (a broad range as the bankruptcy form does not provide a space to be more specific).

Gizmo Brew Works/Roth Brewing did not share a reorganization or funding plan in its bankruptcy filing. An email request for comment sent through the company's contact page was not immediately returned.

bankruptcy pandemic social distancing

Spread & Containment

Revving up tourism: Formula One and other big events look set to drive growth in the hospitality industry

With big events drawing a growing share of of tourism dollars, F1 offers a potential glimpse of the travel industry’s future.

In late 2023, I embarked on my first Formula One race experience, attending the first-ever Las Vegas Grand Prix. I had never been to an F1 race; my interest was sparked during the pandemic, largely through the Netflix series “Formula 1: Drive to Survive.”

But I wasn’t just attending as a fan. As the inaugural chair of the University of Florida’s department of tourism, hospitality and event management, I saw this as an opportunity. Big events and festivals represent a growing share of the tourism market – as an educator, I want to prepare future leaders to manage them.

And what better place to learn how to do that than in the stands of the Las Vegas Grand Prix?

The future of tourism is in events and experiences

Tourism is fun, but it’s also big business: In the U.S. alone, it’s a US$2.6 trillion industry employing 15 million people. And with travelers increasingly planning their trips around events rather than places, both industry leaders and academics are paying attention.

Event tourism is also key to many cities’ economic development strategies – think Chicago and its annual Lollapalooza music festival, which has been hosted in Grant Park since 2005. In 2023, Lollapalooza generated an estimated $422 million for the local economy and drew record-breaking crowds to the city’s hotels.

That’s why when Formula One announced it would be making a 10-year commitment to host races in Las Vegas, the region’s tourism agency was eager to spread the news. The 2023 grand prix eventually generated $100 million in tax revenue, the head of that agency later announced.

Why Formula One?

Formula One offers a prime example of the economic importance of event tourism. In 2022, Formula One generated about $2.6 billion in total revenues, according to the latest full-year data from its parent company. That’s up 20% from 2021 and 27% from 2019, the last pre-COVID year. A record 5.7 million fans attended Formula One races in 2022, up 36% from 2019.

This surge in interest can be attributed to expanded broadcasting rights, sponsorship deals and a growing global fan base. And, of course, the in-person events make a lot of money – the cheapest tickets to the Las Vegas Grand Prix were $500.

That’s why I think of Formula One as more than just a pastime: It’s emblematic of a major shift in the tourism industry that offers substantial job opportunities. And it takes more than drivers and pit crews to make Formula One run – it takes a diverse range of professionals in fields such as event management, marketing, engineering and beyond.

This rapid industry growth indicates an opportune moment for universities to adapt their hospitality and business curricula and prepare students for careers in this profitable field.

How hospitality and business programs should prepare students

To align with the evolving landscape of mega-events like Formula One races, hospitality schools should, I believe, integrate specialized training in event management, luxury hospitality and international business. Courses focusing on large-scale event planning, VIP client management and cross-cultural communication are essential.

Another area for curriculum enhancement is sustainability and innovation in hospitality. Formula One, like many other companies, has increased its emphasis on environmental responsibility in recent years. While some critics have been skeptical of this push, I think it makes sense. After all, the event tourism industry both contributes to climate change and is threatened by it. So, programs may consider incorporating courses in sustainable event management, eco-friendly hospitality practices and innovations in sustainable event and tourism.

Additionally, business programs may consider emphasizing strategic marketing, brand management and digital media strategies for F1 and for the larger event-tourism space. As both continue to evolve, understanding how to leverage digital platforms, engage global audiences and create compelling brand narratives becomes increasingly important.

Beyond hospitality and business, other disciplines such as material sciences, engineering and data analytics can also integrate F1 into their curricula. Given the younger generation’s growing interest in motor sports, embedding F1 case studies and projects in these programs can enhance student engagement and provide practical applications of theoretical concepts.

Racing into the future: Formula One today and tomorrow

F1 has boosted its outreach to younger audiences in recent years and has also acted to strengthen its presence in the U.S., a market with major potential for the sport. The 2023 Las Vegas race was a strategic move in this direction. These decisions, along with the continued growth of the sport’s fan base and sponsorship deals, underscore F1’s economic significance and future potential.

Looking ahead in 2024, Formula One seems ripe for further expansion. New races, continued advancements in broadcasting technology and evolving sponsorship models are expected to drive revenue growth. And Season 6 of “Drive to Survive” will be released on Feb. 23, 2024. We already know that was effective marketing – after all, it inspired me to check out the Las Vegas Grand Prix.

I’m more sure than ever that big events like this will play a major role in the future of tourism – a message I’ll be imparting to my students. And in my free time, I’m planning to enhance my quality of life in 2024 by synchronizing my vacations with the F1 calendar. After all, nothing says “relaxing getaway” quite like the roar of engines and excitement of the racetrack.

Rachel J.C. Fu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

spread pandemic-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex