International

One Step Closer To Recession: Goldman Cuts S&P Price Target To 4,300; Slashes GDP Forecast

One Step Closer To Recession: Goldman Cuts S&P Price Target To 4,300; Slashes GDP Forecast

It took Goldman three months to slash its (widely…

It took Goldman three months to slash its (widely mocked) 2022 year-end S&P price target of 5,100 published in mid-November (at the time we said it would take just a few months for the target to be cut and we were right) to 4,900 in mid-February. Back then Goldman's chief strategist David Kostin listed three scenarios, the third and most bearish of which was that if the US economy tips into a recession, "the typical 24% recession peak-to-trough price decline would reduce the S&P 500 to 3600" to which we said that's what would happen "but before we get there expect another 200 point S&P target in one month, and then another, and then another."

One month later, this is precisely what happened, when in mid-March Goldman's David Kostin again cut his year-end price target to 4,700 (from 4.900), but more importantly, Kostin grudgingly raised the odds of a recession writing that "the current S&P 500 index level of 4260 suggests roughly a 40% likelihood of a downside recessionary case." He then noted that in such a "recession" scenario, the bank expects reduced earnings and valuation multiples would cause the S&P 500 to decline by 15% to 3600, similar to the 24% drop he had warned previously (Goldman also noted that this represents a 15% drop from current levels and is probably sufficient to trigger the Fed's put).

So fast forward another two months, when our prediction that Goldman would continue to slash its S&P price target by 200 points every month or so was spot on again, because as of this weekend, two months after Goldman cut its S&P target to 4,700, the bank's chief equity strategist has just published his latest forecast (full note available to professional subscribers), taking down the bank's price target to 4,300 (or 200 points per month for two months); as a reminder this was 5,100 just three months ago!

How does Kostin explain this dramatic reversal in his original cheerful forecast, which apparently could not anticipate any of the things that took place in the past few months? Here's how:

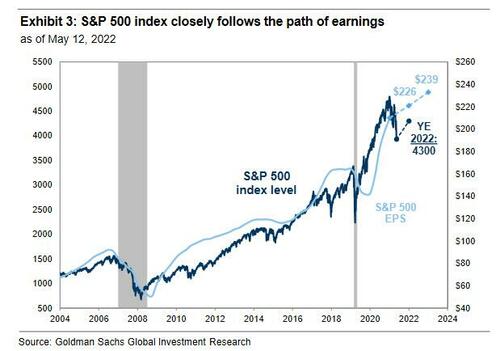

We revise our forecasts for earnings, interest rates, and the yield gap. We lower our S&P 500 year-end 2022 price target to 4300 (from 4700). Our new price target represents a 7% return from today. Our 3-month forecast equals 4000, with expected gains likely coming later in the year.

Finally admitting what we have been saying all along, Kostin concedes that "much higher equity prices in the near-term would ease financial conditions and be antithetical to the Fed’s goal of slowing economic growth", in other words, every time stocks jumped it would only prompt Powell to come out with even stronger hawkish jawboning .

That said, while Goldman expects an overshoot to 4,000 in the near-term (or undershoot since the S&P dropped as low as 3,855 on Thursday, touching the edge of a bear market), the bank remains somewhat hopeful that the worst is now behind us and "a contraction in economic growth is priced in equities and our baseline forecast suggests the worst of the decline is likely behind us assuming a recession is averted." Kostin also assumes that as the year progresses "investors will gain confidence about decelerating inflation, the path of Fed tightening, and recession risk, and equities will rise modestly driven by EPS growth."

Kostin then breaks down the revision in his forecast by factoring in for a stronger than expected Q1 earnings, offset by everything else deteriorating:

1Q earnings season was better-than-feared. Consensus expected +5% year/year growth in S&P 500 EPS, but firms realized +11%. Both sales and margins posted positive surprises. Analyst revisions to 2022 and 2023 have been slightly positive, mostly driven by Energy. We raise our 2022 S&P 500 top-down EPS growth forecast to +8% (vs. +5% previously). We maintain our 2023 EPS growth forecast of +6%. Our revised S&P 500 EPS estimates equal $226 and $239. Faster sales growth and better-than-feared Financials earnings are the primary drivers of our revision. Our net margin forecast remains unchanged. We expect margins will rise by 11 bp to 12.3% in 2022. However, excluding Energy, we forecast net profit margins will contract by 22 bp as input cost pressures weigh on companies.

Our sales, margin, and earnings forecasts remain below bottom-up consensus. Our economists’ 2022 real US GDP growth forecast is below-consensus and China’s zero COVID policy poses a clear downside risk to EPS growth. From a revenue perspective, we expect the headwind from a stronger trade-weighted dollar will need to be incorporated into analyst models. Investors have already started to reflect this risk; our domestic sales basket (GSTHAINT) has outperformed our international sales basket (GSTHINTL) by 10 pp YTD. While quarterly net profit margins have slipped modestly from their peak in 2Q 2021 to 12.1% in 1Q 2022, consensus expects an expansion during in 2H 2022, which appears too optimistic in our view. However, we believe it will take time for analysts to trim their forecasts closer to our top-down estimate. Our S&P 500 valuation and index forecasts assume that market participants price the index at year-end 2022 based on the consensus 2023E estimate of $250.

Higher interest rates. Our Rates strategists now expect the nominal 10-year US Treasury yield to rise to 3.3% at year-end 2022 (vs. 2.7% previously) driven by real yields. We assume real yields will end 2022 at 0.5% (vs. 0% previously).

Our forecast is that the P/E remains unchanged from today at 17x. Previously, we assumed the low real rate environment would support a P/E of 20x, 10% below the valuation at start of the year. But YTD the market has priced the equivalent of 8 additional 25 bp Fed hikes and real rates have risen sharply. During the last 8 weeks real rates have surged from -1.0% to +0.2%. Our revised outlook of lower growth and higher rates no longer supports meaningful P/E expansion. Our new P/E multiple forecast ranks in the 70th historical percentile and is consistent with pre-pandemic multiples, but below the past cycle’s peak of 18x in 2018. In our baseline, the relative valuation of stocks vs. real rates would rank in the 46th percentile vs history.

Lower yield gap. We expect the gap between the S&P 500 EPS yield and real 10-year US Treasury yield will narrow modestly to 530 bp (vs. 560 bp today). This yield gap would match the level experienced in April 2021 but remain above the average since 1990. We model the yield gap as a function of economic growth, policy uncertainty, the size of the Fed balance sheet, and consumer confidence. By the end of the year, our baseline assumes a slight improvement in growth expectations relative to the pessimistic outlook currently priced by cyclical vs. defensive industries. Valuation will benefit from reduced policy uncertainty and higher consumer confidence. These positive dynamics should more than offset the headwind from tightening financial conditions and allow the earnings yield gap to compress.

While Kostin tries to sound hopeful, the reality is that for the third time in a row the Goldman chief strategist not accidentally brings up that in a "downside" scenario, "a recession would push the S&P 500 11% lower to 3600", which is just slightly above the level Morgan Stanley expects stocks drop to in this bear market before they reverse. However, in a novel twist, today for the first time Kostin admits that if by year-end the economy is poised to enter a recession in 2023, "a combination of reduced EPS estimates and a wider yield gap would drive a lower index level" suggesting that the S&P may slide well below 3,600:

Earnings typically fall by 13% from peak-to-trough during recessions. However, equity prices move ahead of earnings. We assume by year-end the current 2023 EPS estimate of $250 would be cut by 7%, consistent with history. Our macro model implies the yield gap widens to 700 bp and the P/E multiple narrows to 15x.

Translation: just above 3,400.

In another downside scenario, Kostin writes that while the economy may avoid recession, real rates could continue to march higher, which would lead to a lower valuation multiple pushing the S&P 500 index down by 6% to 3800. In this scenario, if the Fed is forced to hike by more than Goldman economists expect and real rates rise to 1% - similar to the peak reached during the last cycle in 2018 - Goldman's macro model suggests that higher rates will more than offset the lower yield gap. In this scenario, the forward P/E would equal 16x, the lowest level since 2020.

Bottom line: Goldman has thrown in the towel and the bank which in early February expected stocks to hit 5,100 now says don't be surprise if they drop to 3,400. And that's why the David Kostins of the world get paid the big bucks.

But wait, there more...

In another confirmation of our skepticism, Goldman's chief economist Jan Hatzius published a note on Sunday in which he again cut his overly optimistic GDP forecast (having done so most recently in March), and now expects GDP growth as follows:

- Q2 '22 to 2.5% from 1.5%

- Q3 '22 to 2.25% from 2.5%

- Q4 '22 to 1.5% from 2.5%

- Q1 '23 to 1.25%

- Q2 '23 to 1.5%

- Q3 '23 to 1.5%

- Q4 '23 to 1.5%

And visually:

These changes imply a downgrade in 2022 GDP growth to +2.4% on an annual basis (vs. +2.6% previously) and to +1¼% on a Q4/Q4 basis (vs. 1.6%), and a downgrade in 2023 growth to +1.6% on an annual basis (vs. +2.2%) and to +1½% on a Q4/Q4 basis (vs. +2.0%). In other words, just as we said in March, the hockeystick forecast that Goldman laughably presented two months ago has not only flattened but has inverted.

Of course, Goldman has refused to forecast a recession (yet), and instead frames the continuing slowdown (as a reminder Goldman was nowhere near the -1.4% Q1 GDP print), as a "necessary growth slowdown." According to Goldman, the slowdown is a byproduct of the Fed's tightening in financial conditions, and the bank thinks the rate hikes that are currently priced into financial conditions "are in the ballpark of what is ultimately needed to restore balance to the labor market and cool wage and price pressures. We therefore expect that the recent tightening in financial conditions will persist, in part because we think the Fed will deliver on what is priced."

That said, not even Goldman is confident that a slowdown won't push the economy into recession, and cautions that job openings remains "extremely high (+4.5mn vs. pre-pandemic level; right chart, Exhibit 1) and less likely to moderate on their own. And the jobs-workers gap probably cannot meaningfully narrow without a moderation in job openings, and wage growth probably cannot settle back to a sustainable level while the jobs-workers gap remains very elevated. Therefore, the main challenge for the FOMC as it attempts to lower inflation is to convince companies to shelve some of their expansion plans and close enough job openings to restore balance to the labor market, a view Chair Powell endorsed at the May FOMC press conference."

It's not just GDP that will get hit: the labor market will too. As the bank concludes in its downward revision, while the slowdown in growth should help lower job openings, "it is also likely to raise the unemployment rate a bit, particularly since the job openings rate

typically only falls when unemployment spikes in recessions." Of course, Goldman remains optimistic "that a sharp rise in the unemployment rate can be avoided, especially since typically the job openings rate declines more and the unemployment rate increases less when the job openings rate is very elevated, like it is today."

Although we continue to expect that momentum in job gains will push then unemployment rate to a low of 3.4% in the next few months, we now expect that the unemployment rate will subsequently rise back to 3.5% at end-2022, and rise further to 3.7% at end-2023.

And since Goldman has been always wrong in its economic forecasts in the past year (just see the bank's horrific CPI predictions) here is our translation of the above: expect the labor market to soon enter freefall, one which will force the Fed to not only reverse its tightening and QT plans, but to go straight from rate cuts to NIRP and back to QE again.

And just to confirm that a recession is now inevitable (as is the obvious Fed response) none other than the former boss of both Kostin and Hatzius, former Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein, spoke on CBS’s “Face the Nation” on Sunday, and urged companies and consumers to gird for a US recession, saying it’s a “very, very high risk.”

"Do you think we're headed towards recession?" @margbrennan asks Goldman Sachs Senior Chairman Lloyd Blankfein amid U.S. inflation.

— Face The Nation (@FaceTheNation) May 15, 2022

"It's definitely a risk...If I were a consumer, I'd be prepared for it, but it's not baked in the cake." pic.twitter.com/IehxU4wSo6

“If I were running a big company, I would be very prepared for it. If I was a consumer, I’d be prepared for it.” A recession is “not baked in the cake” and there’s a “narrow path” to avoid it, said the CEO who lost his job after infamously enabling Obama golfing buddy, former Malaysia PM Najib Razak, to loot billions from 1MDB.

Blankfein noted that while some of the inflation “will go away” as supply chains unsnarl and Covid-19 lockdowns in China ease, “some of these things are a little bit stickier, like energy prices.”

“How comfortable are we now to rely on those supply chains that are not within the borders of the United States and we can’t control?” Blankfein said. “Do we feel good about getting all our semiconductors from Taiwan, which is again, an object of China.”

Bottom line: the question is not if but when the next recession hits, and not if but when the Fed responds with aggressive rates cuts and QE.

The full Goldman notes are available to professional subs in the usual place.

International

United Airlines adds new flights to faraway destinations

The airline said that it has been working hard to "find hidden gem destinations."

Since countries started opening up after the pandemic in 2021 and 2022, airlines have been seeing demand soar not just for major global cities and popular routes but also for farther-away destinations.

Numerous reports, including a recent TripAdvisor survey of trending destinations, showed that there has been a rise in U.S. traveler interest in Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea and Vietnam as well as growing tourism traction in off-the-beaten-path European countries such as Slovenia, Estonia and Montenegro.

Related: 'No more flying for you': Travel agency sounds alarm over risk of 'carbon passports'

As a result, airlines have been looking at their networks to include more faraway destinations as well as smaller cities that are growing increasingly popular with tourists and may not be served by their competitors.

Shutterstock

United brings back more routes, says it is committed to 'finding hidden gems'

This week, United Airlines (UAL) announced that it will be launching a new route from Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) to Morocco's Marrakesh. While it is only the country's fourth-largest city, Marrakesh is a particularly popular place for tourists to seek out the sights and experiences that many associate with the country — colorful souks, gardens with ornate architecture and mosques from the Moorish period.

More Travel:

- A new travel term is taking over the internet (and reaching airlines and hotels)

- The 10 best airline stocks to buy now

- Airlines see a new kind of traveler at the front of the plane

"We have consistently been ahead of the curve in finding hidden gem destinations for our customers to explore and remain committed to providing the most unique slate of travel options for their adventures abroad," United's SVP of Global Network Planning Patrick Quayle, said in a press statement.

The new route will launch on Oct. 24 and take place three times a week on a Boeing 767-300ER (BA) plane that is equipped with 46 Polaris business class and 22 Premium Plus seats. The plane choice was a way to reach a luxury customer customer looking to start their holiday in Marrakesh in the plane.

Along with the new Morocco route, United is also launching a flight between Houston (IAH) and Colombia's Medellín on Oct. 27 as well as a route between Tokyo and Cebu in the Philippines on July 31 — the latter is known as a "fifth freedom" flight in which the airline flies to the larger hub from the mainland U.S. and then goes on to smaller Asian city popular with tourists after some travelers get off (and others get on) in Tokyo.

United's network expansion includes new 'fifth freedom' flight

In the fall of 2023, United became the first U.S. airline to fly to the Philippines with a new Manila-San Francisco flight. It has expanded its service to Asia from different U.S. cities earlier last year. Cebu has been on its radar amid growing tourist interest in the region known for marine parks, rainforests and Spanish-style architecture.

With the summer coming up, United also announced that it plans to run its current flights to Hong Kong, Seoul, and Portugal's Porto more frequently at different points of the week and reach four weekly flights between Los Angeles and Shanghai by August 29.

"This is your normal, exciting network planning team back in action," Quayle told travel website The Points Guy of the airline's plans for the new routes.

stocks pandemic south korea japan hong kong europeanInternational

Walmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

The retail superstore is adding a new feature to its Walmart+ plan — and customers will be happy.

It's just been a few days since Target (TGT) launched its new Target Circle 360 paid membership plan.

The plan offers free and fast shipping on many products to customers, initially for $49 a year and then $99 after the initial promotional signup period. It promises to be a success, since many Target customers are loyal to the brand and will go out of their way to shop at one instead of at its two larger peers, Walmart and Amazon.

Related: Walmart makes a major price cut that will delight customers

And stop us if this sounds familiar: Target will rely on its more than 2,000 stores to act as fulfillment hubs.

This model is a proven winner; Walmart also uses its more than 4,600 stores as fulfillment and shipping locations to get orders to customers as soon as possible.

Sometimes, this means shipping goods from the nearest warehouse. But if a desired product is in-store and closer to a customer, it reduces miles on the road and delivery time. It's a kind of logistical magic that makes any efficiency lover's (or retail nerd's) heart go pitter patter.

Walmart rolls out answer to Target's new membership tier

Walmart has certainly had more time than Target to develop and work out the kinks in Walmart+. It first launched the paid membership in 2020 during the height of the pandemic, when many shoppers sheltered at home but still required many staples they might ordinarily pick up at a Walmart, like cleaning supplies, personal-care products, pantry goods and, of course, toilet paper.

It also undercut Amazon (AMZN) Prime, which costs customers $139 a year for free and fast shipping (plus several other benefits including access to its streaming service, Amazon Prime Video).

Walmart+ costs $98 a year, which also gets you free and speedy delivery, plus access to a Paramount+ streaming subscription, fuel savings, and more.

If that's not enough to tempt you, however, Walmart+ just added a new benefit to its membership program, ostensibly to compete directly with something Target now has: ultrafast delivery.

Target Circle 360 particularly attracts customers with free same-day delivery for select orders over $35 and as little as one-hour delivery on select items. Target executes this through its Shipt subsidiary.

We've seen this lightning-fast delivery speed only in snippets from Amazon, the king of delivery efficiency. Who better to take on Target, though, than Walmart, which is using a similar store-as-fulfillment-center model?

"Walmart is stepping up to save our customers even more time with our latest delivery offering: Express On-Demand Early Morning Delivery," Walmart said in a statement, just a day after Target Circle 360 launched. "Starting at 6 a.m., earlier than ever before, customers can enjoy the convenience of On-Demand delivery."

Walmart (WMT) clearly sees consumers' desire for near-instant delivery, which obviously saves time and trips to the store. Rather than waiting a day for your order to show up, it might be on your doorstep when you wake up.

Consumers also tend to spend more money when they shop online, and they remain stickier as paying annual members. So, to a growing number of retail giants, almost instant gratification like this seems like something worth striving for.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemic mexicoGovernment

President Biden Delivers The “Darkest, Most Un-American Speech Given By A President”

President Biden Delivers The "Darkest, Most Un-American Speech Given By A President"

Having successfully raged, ranted, lied, and yelled through…

Having successfully raged, ranted, lied, and yelled through the State of The Union, President Biden can go back to his crypt now.

Whatever 'they' gave Biden, every American man, woman, and the other should be allowed to take it - though it seems the cocktail brings out 'dark Brandon'?

Tl;dw: Biden's Speech tonight ...

-

Fund Ukraine.

-

Trump is threat to democracy and America itself.

-

Abortion is good.

-

American Economy is stronger than ever.

-

Inflation wasn't Biden's fault.

-

Illegals are Americans too.

-

Republicans are responsible for the border crisis.

-

Trump is bad.

-

Biden stands with trans-children.

-

J6 was the worst insurrection since the Civil War.

(h/t @TCDMS99)

Tucker Carlson's response sums it all up perfectly:

"that was possibly the darkest, most un-American speech given by an American president. It wasn't a speech, it was a rant..."

Carlson continued: "The true measure of a nation's greatness lies within its capacity to control borders, yet Bid refuses to do it."

"In a fair election, Joe Biden cannot win"

And concluded:

“There was not a meaningful word for the entire duration about the things that actually matter to people who live here.”

Victor Davis Hanson added some excellent color, but this was probably the best line on Biden:

"he doesn't care... he lives in an alternative reality."

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) March 8, 2024

* * *

Watch SOTU Live here...

* * *

Mises' Connor O'Keeffe, warns: "Be on the Lookout for These Lies in Biden's State of the Union Address."

On Thursday evening, President Joe Biden is set to give his third State of the Union address. The political press has been buzzing with speculation over what the president will say. That speculation, however, is focused more on how Biden will perform, and which issues he will prioritize. Much of the speech is expected to be familiar.

The story Biden will tell about what he has done as president and where the country finds itself as a result will be the same dishonest story he's been telling since at least the summer.

He'll cite government statistics to say the economy is growing, unemployment is low, and inflation is down.

Something that has been frustrating Biden, his team, and his allies in the media is that the American people do not feel as economically well off as the official data says they are. Despite what the White House and establishment-friendly journalists say, the problem lies with the data, not the American people's ability to perceive their own well-being.

As I wrote back in January, the reason for the discrepancy is the lack of distinction made between private economic activity and government spending in the most frequently cited economic indicators. There is an important difference between the two:

-

Government, unlike any other entity in the economy, can simply take money and resources from others to spend on things and hire people. Whether or not the spending brings people value is irrelevant

-

It's the private sector that's responsible for producing goods and services that actually meet people's needs and wants. So, the private components of the economy have the most significant effect on people's economic well-being.

Recently, government spending and hiring has accounted for a larger than normal share of both economic activity and employment. This means the government is propping up these traditional measures, making the economy appear better than it actually is. Also, many of the jobs Biden and his allies take credit for creating will quickly go away once it becomes clear that consumers don't actually want whatever the government encouraged these companies to produce.

On top of all that, the administration is dealing with the consequences of their chosen inflation rhetoric.

Since its peak in the summer of 2022, the president's team has talked about inflation "coming back down," which can easily give the impression that it's prices that will eventually come back down.

But that's not what that phrase means. It would be more honest to say that price increases are slowing down.

Americans are finally waking up to the fact that the cost of living will not return to prepandemic levels, and they're not happy about it.

The president has made some clumsy attempts at damage control, such as a Super Bowl Sunday video attacking food companies for "shrinkflation"—selling smaller portions at the same price instead of simply raising prices.

In his speech Thursday, Biden is expected to play up his desire to crack down on the "corporate greed" he's blaming for high prices.

In the name of "bringing down costs for Americans," the administration wants to implement targeted price ceilings - something anyone who has taken even a single economics class could tell you does more harm than good. Biden would never place the blame for the dramatic price increases we've experienced during his term where it actually belongs—on all the government spending that he and President Donald Trump oversaw during the pandemic, funded by the creation of $6 trillion out of thin air - because that kind of spending is precisely what he hopes to kick back up in a second term.

If reelected, the president wants to "revive" parts of his so-called Build Back Better agenda, which he tried and failed to pass in his first year. That would bring a significant expansion of domestic spending. And Biden remains committed to the idea that Americans must be forced to continue funding the war in Ukraine. That's another topic Biden is expected to highlight in the State of the Union, likely accompanied by the lie that Ukraine spending is good for the American economy. It isn't.

It's not possible to predict all the ways President Biden will exaggerate, mislead, and outright lie in his speech on Thursday. But we can be sure of two things. The "state of the Union" is not as strong as Biden will say it is. And his policy ambitions risk making it much worse.

* * *

The American people will be tuning in on their smartphones, laptops, and televisions on Thursday evening to see if 'sloppy joe' 81-year-old President Joe Biden can coherently put together more than two sentences (even with a teleprompter) as he gives his third State of the Union in front of a divided Congress.

President Biden will speak on various topics to convince voters why he shouldn't be sent to a retirement home.

The state of our union under President Biden: three years of decline. pic.twitter.com/Da1KOIb3eR

— Speaker Mike Johnson (@SpeakerJohnson) March 7, 2024

According to CNN sources, here are some of the topics Biden will discuss tonight:

Economic issues: Biden and his team have been drafting a speech heavy on economic populism, aides said, with calls for higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy – an attempt to draw a sharp contrast with Republicans and their likely presidential nominee, Donald Trump.

Health care expenses: Biden will also push for lowering health care costs and discuss his efforts to go after drug manufacturers to lower the cost of prescription medications — all issues his advisers believe can help buoy what have been sagging economic approval ratings.

Israel's war with Hamas: Also looming large over Biden's primetime address is the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, which has consumed much of the president's time and attention over the past few months. The president's top national security advisers have been working around the clock to try to finalize a ceasefire-hostages release deal by Ramadan, the Muslim holy month that begins next week.

An argument for reelection: Aides view Thursday's speech as a critical opportunity for the president to tout his accomplishments in office and lay out his plans for another four years in the nation's top job. Even though viewership has declined over the years, the yearly speech reliably draws tens of millions of households.

Sources provided more color on Biden's SOTU address:

The speech is expected to be heavy on economic populism. The president will talk about raising taxes on corporations and the wealthy. He'll highlight efforts to cut costs for the American people, including pushing Congress to help make prescription drugs more affordable.

Biden will talk about the need to preserve democracy and freedom, a cornerstone of his re-election bid. That includes protecting and bolstering reproductive rights, an issue Democrats believe will energize voters in November. Biden is also expected to promote his unity agenda, a key feature of each of his addresses to Congress while in office.

Biden is also expected to give remarks on border security while the invasion of illegals has become one of the most heated topics among American voters. A majority of voters are frustrated with radical progressives in the White House facilitating the illegal migrant invasion.

It is probable that the president will attribute the failure of the Senate border bill to the Republicans, a claim many voters view as unfounded. This is because the White House has the option to issue an executive order to restore border security, yet opts not to do so

Maybe this is why?

Most Americans are still unaware that the census counts ALL people, including illegal immigrants, for deciding how many House seats each state gets!

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 7, 2024

This results in Dem states getting roughly 20 more House seats, which is another strong incentive for them not to deport illegals.

While Biden addresses the nation, the Biden administration will be armed with a social media team to pump propaganda to at least 100 million Americans.

"The White House hosted about 70 creators, digital publishers, and influencers across three separate events" on Wednesday and Thursday, a White House official told CNN.

Not a very capable social media team...

The State of Confusion https://t.co/C31mHc5ABJ

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) March 7, 2024

The administration's move to ramp up social media operations comes as users on X are mostly free from government censorship with Elon Musk at the helm. This infuriates Democrats, who can no longer censor their political enemies on X.

Meanwhile, Democratic lawmakers tell Axios that the president's SOTU performance will be critical as he tries to dispel voter concerns about his elderly age. The address reached as many as 27 million people in 2023.

"We are all nervous," said one House Democrat, citing concerns about the president's "ability to speak without blowing things."

The SOTU address comes as Biden's polling data is in the dumps.

BetOnline has created several money-making opportunities for gamblers tonight, such as betting on what word Biden mentions the most.

As well as...

We will update you when Tucker Carlson's live feed of SOTU is published.

Fuck it. We’ll do it live! Thursday night, March 7, our live response to Joe Biden’s State of the Union speech. pic.twitter.com/V0UwOrgKvz

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) March 6, 2024

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 hours ago

International3 hours agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International1 month ago

International1 month agoWar Delirium

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex