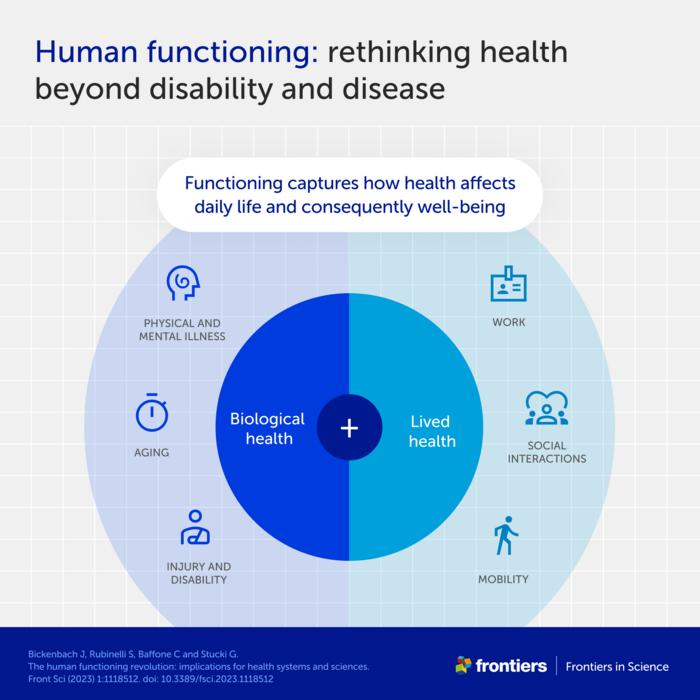

The term ‘well-being’ entered popular vocabulary during the Covid-19 pandemic soon after ‘lockdown’ and ‘quarantine’. We quickly discovered that without the ability to take walks, socialize, and work, our well-being suffered. Health was suddenly more than just the state of our bodies – it also depended on our ability to engage in activities that matter to us.

Though this was a revelation to many, the World Health Organization (WHO) had already begun this rethinking of health. It created a new concept and assessment framework to capture the multi-dimensional nature of our everyday health experience, called ‘human functioning.

“Despite its great promise, this new tool has not been implemented widely in healthcare and policy. Our team’s goal is to make it happen,” said Prof Gerold Stucki, a senior member of a research team at Swiss Paraplegic Research and the University of Lucerne, Switzerland.

In their article published in Frontiers in Science, Stucki and colleagues unveil an innovative framework for integrating the assessment and treatment of functioning into health and social systems. “We believe this approach can profoundly change health practice, education, research, and policy,” added Prof Jerome Bickenbach.

Human functioning: the missing link between health and well-being

Human functioning augments the traditional biomedical approach by adding the ‘lived health’ dimension. This aspect of health reflects individuals’ capacity to engage in a range of activities, from eating independently to socializing and working. Since our biological and lived health are intertwined, this approach provides a more complete understanding of human health.

Mobility impairments are a clear example of why an assessment of functioning is important. A disabled person may have poor lived health in a physical environment that is not accessible. But their functioning can be enhanced through assistive devices and changes to the built environment.

“Functioning also clarifies how our health is linked to our well-being,” Prof Sara Rubinelli explained. “It isn’t just about the absence of disease, injury, or other physical issues, but also the ability to take part in daily life and achieve personal goals. Nurturing individual well-being on a large scale could truly transform our society, ultimately enhancing societal welfare.”

Human functioning data complements morbidity and mortality

To achieve this vision, the team developed a multipronged strategy for implementing standardized assessment of functioning into health and social systems. The first step is to recognize functioning as the third major health indicator.

“Morbidity and mortality are the two main indicators currently used to assess population health and the efficacy of policies and interventions,” said Cristiana Baffone. “While this strategy has brought us enormous benefits, it doesn’t encompass lived health. Recognizing functioning as the third main indictor will bridge this gap. Once we begin systematically collecting functioning data, we can use it to inform and guide public policy.”

The article explains that this approach can also advance the UN’s third Sustainable Development Goal (SDG3): ‘to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all’. Though SDG3 targets both health and well-being, its progress is assessed using mortality and morbidity data. Systematically tracking and analyzing human functioning data across populations can guide efforts to achieve the full vision of SDG3.

Human functioning sciences: new field can fuel the functioning revolution

Integrating functioning into healthcare is a complex process requiring significant investment and involvement from healthcare providers, policymakers, and the public. One major issue raised by the authors is a general lack of awareness about the extensive potential benefits of this approach, which can be tackled by effective communication campaigns. They also highlight the need for a new generation of researchers, healthcare professionals, and policy entrepreneurs to form a ‘human functioning’ workforce.

“We can facilitate this step by establishing a new scientific field called ‘human functioning sciences’. This field will integrate distinct disciplines to deepen our understanding of health and guide research, healthcare, and policy,” Stucki explained.

The challenges ahead may seem daunting, but rehabilitation is an example of a discipline where functioning has already been well-integrated, helping to define guidelines and driving technical developments.

“Rehabilitation is an evolving success story that can help guide us through the functioning revolution,” said Bickenbach. “While we’re well on our way to resolving methodological challenges, large-scale implementation is still in its infancy. Societal economic investment is essential for realizing the promise of human functioning,” he concluded.

Journal

Frontiers in Science

DOI

10.3389/fsci.2023.1118512

Method of Research

Systematic review

Subject of Research

People

Article Title

The human functioning revolution: implications for health systems and sciences

Article Publication Date

31-May-2023

COI Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.