International

Microsoft Surface Duo review

Microsoft Surface Duo review

In the early days, Microsoft had misgivings about calling the Surface Duo a phone. Asked to define it as such, the company has had the tendency to deflect with comments like, “Surface Duo does much more than make phone calls.” Which, to be fair, it does. And to also be fair, so do most phones. Heck, maybe the company is worried that the idea of a Microsoft Phone still leaves a bitter taste in some mouths.

The Duo is an ambitious device that is very much about Microsoft’s own ambitions with the Surface line. The company doesn’t simply want to be a hardware manufacturer — there are plenty of those in the world. It wants to be at the vanguard of how we use our devices, going forward. It’s a worthy pursuit in some respects.

After all, for all of the innovations we’ve seen in mobile in the past decade, the category feels static. Sure there’s 5G. Next-gen wireless was supposed to give the industry a temporary kick in the pants. That it hasn’t yet has more to do with external forces (the pandemic caught practically everyone off guard), but even so, it hardly represents some radical departure for mobile hardware.

What many manufacturers do seem to agree on is that the next breakthrough in mobile devices will be the ability to fit more screen real estate into one’s pocket. Mobile devices are currently brushing up against the upper threshold of hardware footprint, in terms of what we’re capable of holding in our hands and willing to carrying around in our pockets. Breakthroughs in recent years also appear to have gotten us close to a saturation point in terms of screen-to-body ratio.

Foldable screens are a compelling way forward. After years of promise, the technology finally arrived as screens appeared to be hitting an upper limit. Of course, Samsung’s Galaxy Fold stumbled out of the gate, leaving other devices like the Huawei Mate X scrambling. That product finally launched in China, but seemed to disappear from the conversation in the process. Motorola’s first foldable, meanwhile, was a flat-out dud.

Announced at a Surface event last year, the Duo takes an entirely different approach to the screen problem — one that has strengths and weaknesses when pitted against the current crop of foldables. The solution is a more robust one. The true pain point of foldables has always been the screen itself. Microsoft sidesteps this by simply connecting two screens. That introduces other problems, however, including a sizable gap and bezel combination that puts a decided damper on watching full-screen video.

Microsoft is far from the first company to take a dual-screen approach, of course. ZTE’s Axon M springs to mind. In that case — as with others — the device very much felt like two smartphones stuck together. Launched at the height of ZTE’s experimental phase, it felt like, at best, a shot in the dark. Microsoft, on the other hand, immediately sets its efforts apart with some really solid design. It’s clear that, unlike the ZTE product, the Duo was created from the ground up.

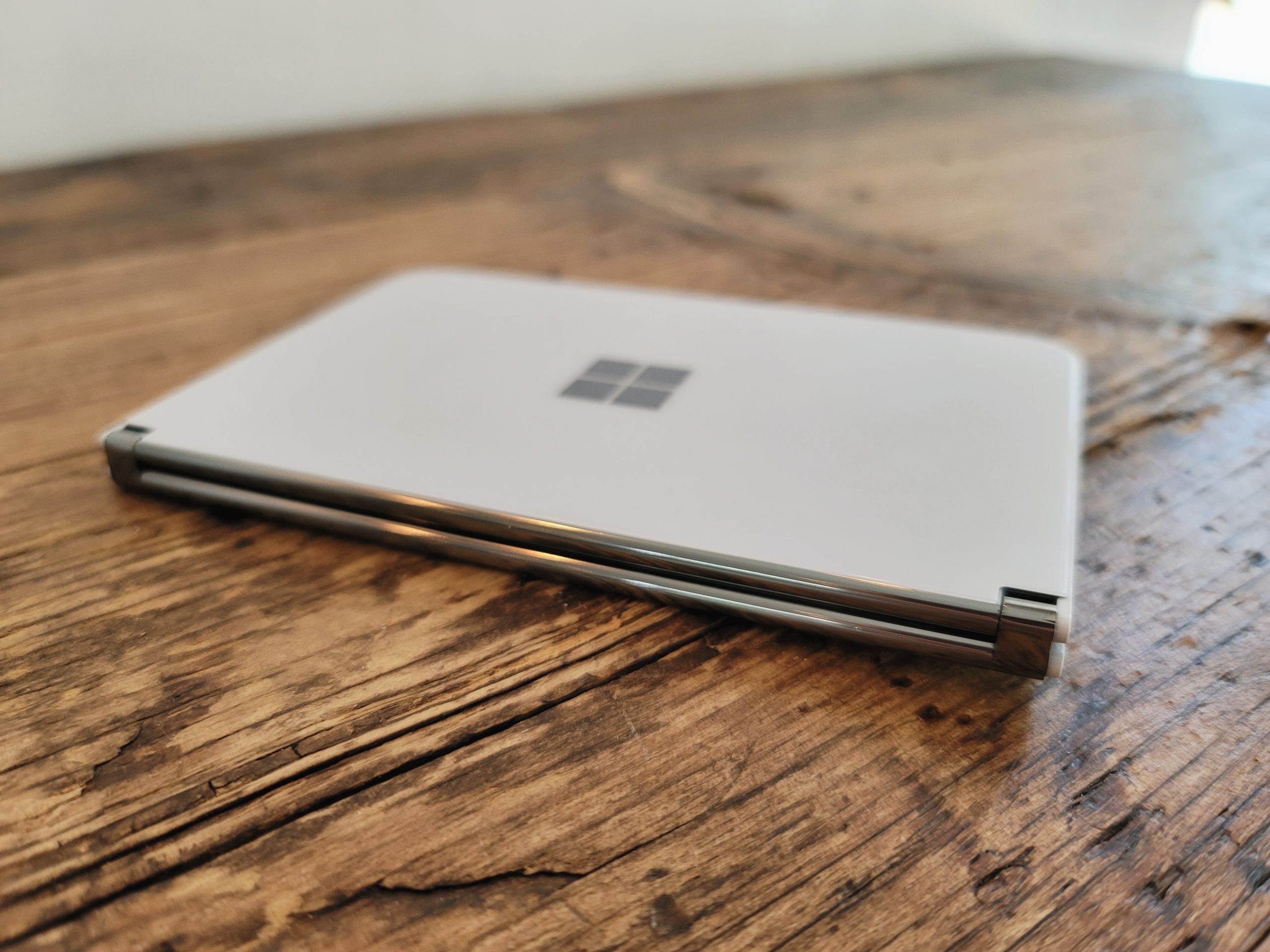

Image Credits: Brian Heater

The last time I wrote about the Duo, it was a “hands-on” that only focused on the device’s hardware. That was due, in part, to the fact that the software wasn’t quite ready at the time of writing. Microsoft was, however, excited to show off the hardware — and for good reason. This really looks and feels nice. Aesthetically, at least, this thing is terrific. It’s no wonder that this is the first device I’ve seen in a while that legitimately had the TechCrunch staff excited.

While the Surface Duo is, indeed, a phone, it’s one that represents exciting potential for the category. And equally importantly, it demonstrates that there is a way to do so without backing into the trappings of the first generation of foldables. In early briefings with the device, Surface lead Panos Panay devoted a LOT of time to breaking down the intricacies of the design decisions made here. To be fair, that’s partially because that’s pretty much his main deal, but I do honestly believe that the company had to engineer some breakthroughs here in order to get hardware that works exactly right, down to a fluid and solid hinge that maintains wired connections between the two displays.

There are, of course, trade-offs. The aforementioned gap between screens is probably the largest. This is primarily a problem when opening a single app across displays (a trick accomplished by dragging and dropping a window onto both screens in a single, fluid movement). This is likely part of the reason the company is positioning this is as far more of a productivity app than an entertainment one — in addition to all of the obvious trappings of a piece of Microsoft hardware.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

The company took great pains to ensure that two separate apps can open on each of the screens. And honestly, the gap is actually kind of a plus when multitasking with two apps open, creating a clear delineation between the two sides. And certain productivity apps make good use of the dual screens when spanning both. Take Gmail, which offers a full inbox on one side and the open selected message on the other. Ditto for using the Amazon app to read a book. Like the abandoned Courier project before it, this is really the perfect form factor for e-book reading — albeit still a bit small for more weary eyes.

There are other pragmatic considerations with the design choices here. The book design means there’s no screen on the exterior. The glass and mirror Windows logo looks lovely, but there’s no easy way to preview notifications. Keep in mind the new Galaxy Fold and Motorola Razr invested a fair amount in the front screen experience on their second-generation devices. Some will no doubt prefer to have a device that’s offline while closed, and I suppose you could always just keep the screens facing outward, if you so chose.

You’ll probably also want to keep the screens facing out if you’re someone who needs your device at the ready to snap a quick photo. Picture taking is really one of the biggest pain points here. There’s no rear camera. Instead, I’m convinced that the company sees most picture taking on the device as secondary to webcam functionality for things like teleconferencing. I do like that experience of having the device standing up and being able to speak into it handsfree (assuming your able to get it to appropriate eye level).

[gallery ids="2043528,2043525,2043529,2043522,2043527,2043523,2043530"]

But when it came to walking around, snapping shots to test the camera, I really found myself fumbling around a lot here. You always feels like you’re between three and five steps away from taking a quick shot. And the fact of the matter is the shots aren’t great. The on-board camera also isn’t really up to the standards of a $1,400 device. Honestly, the whole thing feels like an afterthought. Perhaps I’ve been spoiled after using the Note 20’s camera for the last several weeks, but hopefully Microsoft will prioritize the camera a bit more the next go-round.

Another hardware disappointment for me is the size of the bezels. Microsoft says they’re essentially the minimal viable size so as to not make people accidentally trigger the touchscreen. Which, fair enough. But while it’s not a huge deal aesthetically, it makes the promise of two-hand typing when the device is in laptop mode close to impossible.

That was honestly one of the things I was excited for here. Instead, you’re stuck thumb-typing as you would on any standard smartphone. I have to admit, the Duo was significantly smaller in person than I imagined it would be, for better and worse. Those seeking a fuller typing experience will have to wait for the Neo.

The decision not to include 5G is a curious one. This seems to have been made, in part, over concerns around thinness and form factor. And while 5G isn’t exactly mainstream at this point in 2020, it’s important to attempt to future proof a $1,400 device as much as possible. This isn’t the kind of upgrade most of us make every year or so. By the time the cycle comes back around, LTE is going to feel pretty dated.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

Battery life is pretty solid, owing to the inclusion of two separate batteries, each located beneath a screen. I was able to get about a day and a half of life — that’s also one of the advantages of not having 5G on board, I suppose. Performance also seemed solid for the most part, while working with multiple apps front and center. For whatever reason, however, the Bluetooth connection was lacking. I had all sorts of issues keeping both the Surface Buds and Pixel Buds connected, which can get extremely annoying when attempting to listen to a podcast.

These are the sorts of questions a second-generation device will seek to answer. Ditto for some of the experiential software stuff. There was some bugginess with some of the apps early on. A software update has gone a ways toward addressing much of that, but work needs to be done to offer a seamless dual-screen experience. Some apps like Spotify don’t do a great job spanning screens. Spacing gets weird, things require a bit of finessing on the part of the user. If the Duo proves a more popular form factor, third party developers will hopefully be more eager to fine tune things.

There were other issues, including the occasional blacked out screen on opening, though generally be resolved by closing and reopening the device. Also, Microsoft has opted to only allow one screen to be active at a time when they’re both positioned outward so as to avoid accidentally triggering the back of the touch screen. Switching between displays requires doubling tapping the inactive one.

But Microsoft has added a number of neat tricks like App Groups, which are a quick shortcut to fire up two apps at once. As for why Microsoft went with Android, rather than their own Windows 10, which is designed to be adaptable to a number of different form factors, the answer is refreshingly pragmatic and straightforward. Windows 10 just doesn’t have enough mobile apps. Microsoft clearly wants the Duo to serve as a proof of concept for this new form factor, though one questions whether the company will be able to sufficiently monetize the copycats.

For now, however, that means a lot more selection for the end user, including a ton of Google productivity apps. That’s an important plus given how few of us are tied exclusively to Microsoft productivity apps these days.

As with other experimental form factors, the first generation involves a fair bit of trial and error. Sure, Microsoft no doubt dogfooded the product in-house for a while, but you won’t get a really good idea of how most consumers interact with this manner of device — or precisely what they’re looking for. Six months from now, Microsoft will have a much better picture, and all of those ideas will go into refining the next generation product.

That said, the hardware does feels quite good for a first generation device — even if certain key sacrifices were made in the process. The software will almost certainly continue to be refined over the course of the next year as well. I’d wait a bit on picking it up for that reason alone. The question, ultimately becomes what the cost of early adoption is.

In the grand scheme of foldable devices, maybe $1,400 isn’t that much, perhaps. But compared to the vast majority of smartphone and tablet flagships out there, it’s a lot. Especially for something that still feels like a first generation work in progress. For now, it feels like a significant chunk of the price is invested in novelty and being an early adopter for a promising device.

International

Illegal Immigrants Leave US Hospitals With Billions In Unpaid Bills

Illegal Immigrants Leave US Hospitals With Billions In Unpaid Bills

By Autumn Spredemann of The Epoch Times

Tens of thousands of illegal…

By Autumn Spredemann of The Epoch Times

Tens of thousands of illegal immigrants are flooding into U.S. hospitals for treatment and leaving billions in uncompensated health care costs in their wake.

The House Committee on Homeland Security recently released a report illustrating that from the estimated $451 billion in annual costs stemming from the U.S. border crisis, a significant portion is going to health care for illegal immigrants.

With the majority of the illegal immigrant population lacking any kind of medical insurance, hospitals and government welfare programs such as Medicaid are feeling the weight of these unanticipated costs.

Apprehensions of illegal immigrants at the U.S. border have jumped 48 percent since the record in fiscal year 2021 and nearly tripled since fiscal year 2019, according to Customs and Border Protection data.

Last year broke a new record high for illegal border crossings, surpassing more than 3.2 million apprehensions.

And with that sea of humanity comes the need for health care and, in most cases, the inability to pay for it.

In January, CEO of Denver Health Donna Lynne told reporters that 8,000 illegal immigrants made roughly 20,000 visits to the city’s health system in 2023.

The total bill for uncompensated care costs last year to the system totaled $140 million, said Dane Roper, public information officer for Denver Health. More than $10 million of it was attributed to “care for new immigrants,” he told The Epoch Times.

Though the amount of debt assigned to illegal immigrants is a fraction of the total, uncompensated care costs in the Denver Health system have risen dramatically over the past few years.

The total uncompensated costs in 2020 came to $60 million, Mr. Roper said. In 2022, the number doubled, hitting $120 million.

He also said their city hospitals are treating issues such as “respiratory illnesses, GI [gastro-intenstinal] illnesses, dental disease, and some common chronic illnesses such as asthma and diabetes.”

“The perspective we’ve been trying to emphasize all along is that providing healthcare services for an influx of new immigrants who are unable to pay for their care is adding additional strain to an already significant uncompensated care burden,” Mr. Roper said.

He added this is why a local, state, and federal response to the needs of the new illegal immigrant population is “so important.”

Colorado is far from the only state struggling with a trail of unpaid hospital bills.

Dr. Robert Trenschel, CEO of the Yuma Regional Medical Center situated on the Arizona–Mexico border, said on average, illegal immigrants cost up to three times more in human resources to resolve their cases and provide a safe discharge.

“Some [illegal] migrants come with minor ailments, but many of them come in with significant disease,” Dr. Trenschel said during a congressional hearing last year.

“We’ve had migrant patients on dialysis, cardiac catheterization, and in need of heart surgery. Many are very sick.”

He said many illegal immigrants who enter the country and need medical assistance end up staying in the ICU ward for 60 days or more.

A large portion of the patients are pregnant women who’ve had little to no prenatal treatment. This has resulted in an increase in babies being born that require neonatal care for 30 days or longer.

Dr. Trenschel told The Epoch Times last year that illegal immigrants were overrunning healthcare services in his town, leaving the hospital with $26 million in unpaid medical bills in just 12 months.

ER Duty to Care

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act of 1986 requires that public hospitals participating in Medicare “must medically screen all persons seeking emergency care … regardless of payment method or insurance status.”

The numbers are difficult to gauge as the policy position of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is that it “will not require hospital staff to ask patients directly about their citizenship or immigration status.”

In southern California, again close to the border with Mexico, some hospitals are struggling with an influx of illegal immigrants.

American patients are enduring longer wait times for doctor appointments due to a nursing shortage in the state, two health care professionals told The Epoch Times in January.

A health care worker at a hospital in Southern California, who asked not to be named for fear of losing her job, told The Epoch Times that “the entire health care system is just being bombarded” by a steady stream of illegal immigrants.

“Our healthcare system is so overwhelmed, and then add on top of that tuberculosis, COVID-19, and other diseases from all over the world,” she said.

A newly-enacted law in California provides free healthcare for all illegal immigrants residing in the state. The law could cost taxpayers between $3 billion and $6 billion per year, according to recent estimates by state and federal lawmakers.

In New York, where the illegal immigration crisis has manifested most notably beyond the southern border, city and state officials have long been accommodating of illegal immigrants’ healthcare costs.

Since June 2014, when then-mayor Bill de Blasio set up The Task Force on Immigrant Health Care Access, New York City has worked to expand avenues for illegal immigrants to get free health care.

“New York City has a moral duty to ensure that all its residents have meaningful access to needed health care, regardless of their immigration status or ability to pay,” Mr. de Blasio stated in a 2015 report.

The report notes that in 2013, nearly 64 percent of illegal immigrants were uninsured. Since then, tens of thousands of illegal immigrants have settled in the city.

“The uninsured rate for undocumented immigrants is more than three times that of other noncitizens in New York City (20 percent) and more than six times greater than the uninsured rate for the rest of the city (10 percent),” the report states.

The report states that because healthcare providers don’t ask patients about documentation status, the task force lacks “data specific to undocumented patients.”

Some health care providers say a big part of the issue is that without a clear path to insurance or payment for non-emergency services, illegal immigrants are going to the hospital due to a lack of options.

“It’s insane, and it has been for years at this point,” Dana, a Texas emergency room nurse who asked to have her full name omitted, told The Epoch Times.

Working for a major hospital system in the greater Houston area, Dana has seen “a zillion” migrants pass through under her watch with “no end in sight.” She said many who are illegal immigrants arrive with treatable illnesses that require simple antibiotics. “Not a lot of GPs [general practitioners] will see you if you can’t pay and don’t have insurance.”

She said the “undocumented crowd” tends to arrive with a lot of the same conditions. Many find their way to Houston not long after crossing the southern border. Some of the common health issues Dana encounters include dehydration, unhealed fractures, respiratory illnesses, stomach ailments, and pregnancy-related concerns.

“This isn’t a new problem, it’s just worse now,” Dana said.

Medicaid Factor

One of the main government healthcare resources illegal immigrants use is Medicaid.

All those who don’t qualify for regular Medicaid are eligible for Emergency Medicaid, regardless of immigration status. By doing this, the program helps pay for the cost of uncompensated care bills at qualifying hospitals.

However, some loopholes allow access to the regular Medicaid benefits. “Qualified noncitizens” who haven’t been granted legal status within five years still qualify if they’re listed as a refugee, an asylum seeker, or a Cuban or Haitian national.

Yet the lion’s share of Medicaid usage by illegal immigrants still comes through state-level benefits and emergency medical treatment.

A Congressional report highlighted data from the CMS, which showed total Medicaid costs for “emergency services for undocumented aliens” in fiscal year 2021 surpassed $7 billion, and totaled more than $5 billion in fiscal 2022.

Both years represent a significant spike from the $3 billion in fiscal 2020.

An employee working with Medicaid who asked to be referred to only as Jennifer out of concern for her job, told The Epoch Times that at a state level, it’s easy for an illegal immigrant to access the program benefits.

Jennifer said that when exceptions are sent from states to CMS for approval, “denial is actually super rare. It’s usually always approved.”

She also said it comes as no surprise that many of the states with the highest amount of Medicaid spending are sanctuary states, which tend to have policies and laws that shield illegal immigrants from federal immigration authorities.

Moreover, Jennifer said there are ways for states to get around CMS guidelines. “It’s not easy, but it can and has been done.”

The first generation of illegal immigrants who arrive to the United States tend to be healthy enough to pass any pre-screenings, but Jennifer has observed that the subsequent generations tend to be sicker and require more access to care. If a family is illegally present, they tend to use Emergency Medicaid or nothing at all.

The Epoch Times asked Medicaid Services to provide the most recent data for the total uncompensated care that hospitals have reported. The agency didn’t respond.

Continue reading over at The Epoch Times

International

Fuel poverty in England is probably 2.5 times higher than government statistics show

The top 40% most energy efficient homes aren’t counted as being in fuel poverty, no matter what their bills or income are.

The cap set on how much UK energy suppliers can charge for domestic gas and electricity is set to fall by 15% from April 1 2024. Despite this, prices remain shockingly high. The average household energy bill in 2023 was £2,592 a year, dwarfing the pre-pandemic average of £1,308 in 2019.

The term “fuel poverty” refers to a household’s ability to afford the energy required to maintain adequate warmth and the use of other essential appliances. Quite how it is measured varies from country to country. In England, the government uses what is known as the low income low energy efficiency (Lilee) indicator.

Since energy costs started rising sharply in 2021, UK households’ spending powers have plummeted. It would be reasonable to assume that these increasingly hostile economic conditions have caused fuel poverty rates to rise.

However, according to the Lilee fuel poverty metric, in England there have only been modest changes in fuel poverty incidence year on year. In fact, government statistics show a slight decrease in the nationwide rate, from 13.2% in 2020 to 13.0% in 2023.

Our recent study suggests that these figures are incorrect. We estimate the rate of fuel poverty in England to be around 2.5 times higher than what the government’s statistics show, because the criteria underpinning the Lilee estimation process leaves out a large number of financially vulnerable households which, in reality, are unable to afford and maintain adequate warmth.

Energy security

In 2022, we undertook an in-depth analysis of Lilee fuel poverty in Greater London. First, we combined fuel poverty, housing and employment data to provide an estimate of vulnerable homes which are omitted from Lilee statistics.

We also surveyed 2,886 residents of Greater London about their experiences of fuel poverty during the winter of 2022. We wanted to gauge energy security, which refers to a type of self-reported fuel poverty. Both parts of the study aimed to demonstrate the potential flaws of the Lilee definition.

Introduced in 2019, the Lilee metric considers a household to be “fuel poor” if it meets two criteria. First, after accounting for energy expenses, its income must fall below the poverty line (which is 60% of median income).

Second, the property must have an energy performance certificate (EPC) rating of D–G (the lowest four ratings). The government’s apparent logic for the Lilee metric is to quicken the net-zero transition of the housing sector.

In Sustainable Warmth, the policy paper that defined the Lilee approach, the government says that EPC A–C-rated homes “will not significantly benefit from energy-efficiency measures”. Hence, the focus on fuel poverty in D–G-rated properties.

Generally speaking, EPC A–C-rated homes (those with the highest three ratings) are considered energy efficient, while D–G-rated homes are deemed inefficient. The problem with how Lilee fuel poverty is measured is that the process assumes that EPC A–C-rated homes are too “energy efficient” to be considered fuel poor: the main focus of the fuel poverty assessment is a characteristic of the property, not the occupant’s financial situation.

In other words, by this metric, anyone living in an energy-efficient home cannot be considered to be in fuel poverty, no matter their financial situation. There is an obvious flaw here.

Around 40% of homes in England have an EPC rating of A–C. According to the Lilee definition, none of these homes can or ever will be classed as fuel poor. Even though energy prices are going through the roof, a single-parent household with dependent children whose only income is universal credit (or some other form of benefits) will still not be considered to be living in fuel poverty if their home is rated A-C.

The lack of protection afforded to these households against an extremely volatile energy market is highly concerning.

In our study, we estimate that 4.4% of London’s homes are rated A-C and also financially vulnerable. That is around 171,091 households, which are currently omitted by the Lilee metric but remain highly likely to be unable to afford adequate energy.

In most other European nations, what is known as the 10% indicator is used to gauge fuel poverty. This metric, which was also used in England from the 1990s until the mid 2010s, considers a home to be fuel poor if more than 10% of income is spent on energy. Here, the main focus of the fuel poverty assessment is the occupant’s financial situation, not the property.

Were such alternative fuel poverty metrics to be employed, a significant portion of those 171,091 households in London would almost certainly qualify as fuel poor.

This is confirmed by the findings of our survey. Our data shows that 28.2% of the 2,886 people who responded were “energy insecure”. This includes being unable to afford energy, making involuntary spending trade-offs between food and energy, and falling behind on energy payments.

Worryingly, we found that the rate of energy insecurity in the survey sample is around 2.5 times higher than the official rate of fuel poverty in London (11.5%), as assessed according to the Lilee metric.

It is likely that this figure can be extrapolated for the rest of England. If anything, energy insecurity may be even higher in other regions, given that Londoners tend to have higher-than-average household income.

The UK government is wrongly omitting hundreds of thousands of English households from fuel poverty statistics. Without a more accurate measure, vulnerable households will continue to be overlooked and not get the assistance they desperately need to stay warm.

Torran Semple receives funding from Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) grant EP/S023305/1.

John Harvey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

european uk pandemicGovernment

Looking Back At COVID’s Authoritarian Regimes

After having moved from Canada to the United States, partly to be wealthier and partly to be freer (those two are connected, by the way), I was shocked,…

After having moved from Canada to the United States, partly to be wealthier and partly to be freer (those two are connected, by the way), I was shocked, in March 2020, when President Trump and most US governors imposed heavy restrictions on people’s freedom. The purpose, said Trump and his COVID-19 advisers, was to “flatten the curve”: shut down people’s mobility for two weeks so that hospitals could catch up with the expected demand from COVID patients. In her book Silent Invasion, Dr. Deborah Birx, the coordinator of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, admitted that she was scrambling during those two weeks to come up with a reason to extend the lockdowns for much longer. As she put it, “I didn’t have the numbers in front of me yet to make the case for extending it longer, but I had two weeks to get them.” In short, she chose the goal and then tried to find the data to justify the goal. This, by the way, was from someone who, along with her task force colleague Dr. Anthony Fauci, kept talking about the importance of the scientific method. By the end of April 2020, the term “flatten the curve” had all but disappeared from public discussion.

Now that we are four years past that awful time, it makes sense to look back and see whether those heavy restrictions on the lives of people of all ages made sense. I’ll save you the suspense. They didn’t. The damage to the economy was huge. Remember that “the economy” is not a term used to describe a big machine; it’s a shorthand for the trillions of interactions among hundreds of millions of people. The lockdowns and the subsequent federal spending ballooned the budget deficit and consequent federal debt. The effect on children’s learning, not just in school but outside of school, was huge. These effects will be with us for a long time. It’s not as if there wasn’t another way to go. The people who came up with the idea of lockdowns did so on the basis of abstract models that had not been tested. They ignored a model of human behavior, which I’ll call Hayekian, that is tested every day.

These are the opening two paragraphs of my latest Defining Ideas article, “Looking Back at COVID’s Authoritarian Regimes,” Defining Ideas, March 14, 2024.

Another excerpt:

That wasn’t the only uncertainty. My daughter Karen lived in San Francisco and made her living teaching Pilates. San Francisco mayor London Breed shut down all the gyms, and so there went my daughter’s business. (The good news was that she quickly got online and shifted many of her clients to virtual Pilates. But that’s another story.) We tried to see her every six weeks or so, whether that meant our driving up to San Fran or her driving down to Monterey. But were we allowed to drive to see her? In that first month and a half, we simply didn’t know.

Read the whole thing, which is longer than usual.

(0 COMMENTS) budget deficit coronavirus covid-19 white house fauci trump canada-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International1 week ago

International1 week agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 week ago

International1 week agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Spread & Containment2 days ago

Spread & Containment2 days agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex