Uncategorized

MAA REPORTS FOURTH QUARTER AND FULL YEAR 2022 RESULTS

MAA REPORTS FOURTH QUARTER AND FULL YEAR 2022 RESULTS

PR Newswire

GERMANTOWN, Tenn., Feb. 1, 2023

GERMANTOWN, Tenn., Feb. 1, 2023 /PRNewswire/ — Mid-America Apartment Communities, Inc., or MAA (NYSE: MAA), today announced operating results for the…

MAA REPORTS FOURTH QUARTER AND FULL YEAR 2022 RESULTS

PR Newswire

GERMANTOWN, Tenn., Feb. 1, 2023

GERMANTOWN, Tenn., Feb. 1, 2023 /PRNewswire/ -- Mid-America Apartment Communities, Inc., or MAA (NYSE: MAA), today announced operating results for the quarter ended December 31, 2022.

Fourth Quarter 2022 Operating Results | Three months ended | Year ended December 31, | ||||||||||||||

2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | |||||||||||||

Earnings per common share - diluted | $ | 1.67 | $ | 1.60 | $ | 5.48 | $ | 4.61 | ||||||||

Funds from operations (FFO) per Share - diluted | $ | 2.12 | $ | 2.01 | $ | 8.20 | $ | 7.20 | ||||||||

Core FFO per Share - diluted | $ | 2.32 | $ | 1.90 | $ | 8.50 | $ | 7.01 | ||||||||

A reconciliation of FFO and Core FFO to Net income available for MAA common shareholders, and discussion of the components of FFO and Core FFO, can be found later in this release. FFO per Share – diluted and Core FFO per Share – diluted include diluted common shares and units.

Eric Bolton, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, said, "We closed 2022 with better than expected results and carry good momentum into the new year. As the broader economy adjusts to a higher interest rate environment, we believe that MAA is well positioned to capture another year of solid performance from our existing portfolio. Supported by a strong balance sheet, the company is also in position to capture new growth opportunities that we believe are likely to emerge."

Highlights

- During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA's Same Store Portfolio produced increases in property revenues, operating expenses and Net Operating Income (NOI) of 13.6%, 7.9% and 16.8%, respectively, as compared to the same period in the prior year.

- During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA closed on the disposition of a 396-unit multifamily community in Maryland and a 288-unit multifamily community in the Austin, Texas market for combined gross proceeds of $157.7 million generating a gain on sale of depreciable real estate assets of $82.8 million.

- As of the end of the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA had six communities under development, representing 2,310 units once complete, with a projected total cost of $728.7 million and an estimated $437.0 million remaining to be funded.

- During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA completed the construction of MAA Windmill Hill, a multifamily development community located in the Austin, Texas market and commenced development of multifamily communities MAA Breakwater located in the Tampa, Florida market and MAA Nixie located in the Raleigh/Durham, North Carolina market.

- During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA closed on the pre-purchase of a multifamily community located in the Charlotte, North Carolina market with development expected to begin in the second half of 2023.

- As of the end of the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA had a recently completed development community and a recently acquired community in lease-up. One community is expected to stabilize in the second quarter of 2023 and one in the fourth quarter of 2023.

- During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA completed the lease-up of MAA Westglenn, located in the Denver, Colorado market, MAA Park Point, located in the Houston, Texas market and MAA Robinson located in the Orlando, Florida market.

- MAA completed the redevelopment of 1,327 apartment homes during the fourth quarter of 2022, capturing average rental rate increases of approximately 10% above non-renovated units.

- MAA's balance sheet remains strong with a historically low Net Debt/Adjusted EBITDAre ratio of 3.71x and $1.3 billion of combined cash and available capacity under MAALP's unsecured revolving credit facility as of December 31, 2022.

- Subsequent to the end of the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA settled its forward sale agreements with respect to a total of 1.1 million shares of its common stock for net proceeds of approximately $204 million.

Same Store Portfolio Operating Results

To ensure comparable reporting with prior periods, the Same Store Portfolio includes properties that were owned by MAA and stabilized at the beginning of the previous year.

Same Store Portfolio results for the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022 as compared to the same periods in the prior year are summarized below:

Three months ended December 31, 2022 vs. 2021 | Twelve months ended December 31, 2022 vs. 2021 | |||||||||||||||

Revenues | Expenses (1) | NOI | Average Effective | Revenues | Expenses (2) | NOI | Average Effective | |||||||||

Same Store Operating Growth | 13.6 % | 7.9 % | 16.8 % | 14.9 % | 13.5 % | 7.6 % | 17.1 % | 14.6 % | ||||||||

(1) | Excludes $0.2 million in storm-related expenses related to hurricanes that are recorded in Non-Same Store operating expenses. |

(2) | Excludes $1.8 million in storm-related expenses related to hurricanes that are recorded in Non-Same Store operating expenses. |

A reconciliation of NOI, including Same Store NOI, to Net income available for MAA common shareholders, and discussion of the components of NOI, can be found later in this release.

Same Store Portfolio operating statistics for the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022 are summarized below:

Three months ended December 31, 2022 | Twelve months ended December 31, 2022 | December 31, 2022 | ||||||||||||

Average Effective | Average | Average Effective | Average | Resident Turnover | ||||||||||

Same Store Operating Statistics | $ | 1,646 | 95.6 % | $ | 1,565 | 95.7 % | 46.1 % | |||||||

Same Store Portfolio lease pricing for leases effective during the fourth quarter of 2022, as compared to the prior lease, increased 2.2% for leases to new move-in residents, reflecting typically slower seasonal leasing volumes, and increased 10.1% for renewing leases, which produced an increase of 5.7% for both new and renewing leases on a blended basis. The rent-to-resident-income relationship for new leases signed during the fourth quarter of 2022 remained consistent with recent trends in the range of 22%.

Same Store Portfolio lease pricing for leases effective during the year ended December 31, 2022, as compared to the prior lease, increased 13.0% for leases to new move-in residents and increased 14.8% for renewing leases, which produced an increase of 13.9% for both new and renewing leases on a blended basis.

Acquisition and Disposition Activity

During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA closed on the pre-purchase of a multifamily community, Alta 10th, located in the Charlotte, North Carolina market. The community will be developed through a joint venture with a local developer. Approximately $10 million has been funded as of December 31, 2022, primarily related to land, with development expected to begin in the second half of 2023. During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA also acquired a six acre land parcel in the Raleigh, North Carolina market for approximately $9 million and started development of MAA Nixie on the property. MAA expects to begin multifamily development projects on four to six land parcels currently owned or under contract over the next 18 to 24 months.

During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA closed on the disposition of a 396-unit multifamily community in Maryland and a 288-unit multifamily community in the Austin, Texas market for combined gross proceeds of $157.7 million, resulting in a combined gain on the sale of depreciable real estate assets of $82.8 million.

Development and Lease-up Activity

A summary of MAA's development communities under construction as of the end of the fourth quarter of 2022 is set forth below (dollars in thousands):

Units as of | Development Costs as of | Expected Project | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Total | December 31, 2022 | December 31, 2022 | Completions By Year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Development | Expected | Spend | Expected | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Projects | Total | Delivered | Leased | Total | to Date | Remaining | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

6 | 2,310 | — | — | $ | 728,700 | $ | 291,699 | $ | 437,001 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The expected average stabilized NOI yield on these communities is 5.6%. During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA funded $67.0 million of costs for current and planned projects, including predevelopment activities.

A summary of the total units, cost and the average physical occupancy of MAA's lease-up communities as of the end of the fourth quarter of 2022 is set forth below (dollars in thousands):

Total | As of December 31, 2022 | |||||||||||||

Lease-Up | Total | Physical | Spend | |||||||||||

Projects (1) | Units | Occupancy | to Date | |||||||||||

2 | 694 | 74.6 | % | $ | 198,128 | |||||||||

(1) | Both lease-up projects are expected to stabilize in 2023. |

Property Redevelopment and Repositioning Activity

A summary of MAA's interior redevelopment program and Smart Home technology initiative as of the end of the fourth quarter of 2022 is set forth below:

As of December 31, 2022 | |||||||||||||||||

Units | Units | Average Cost | Increase in Average | ||||||||||||||

Completed | Completed | per Unit | Effective Rent per Unit | ||||||||||||||

QTD | YTD | YTD | YTD | ||||||||||||||

Redevelopment | 1,327 | 6,574 | $ | 6,109 | $ | 133 | |||||||||||

Smart Home | 2,921 | 24,029 | $ | 1,535 | $ | 25 | (1) | ||||||||||

(1) | Projected increase upon lease renewal, opt in or unit turnover. |

As of December 31, 2022, MAA had completed installation of the Smart Home technology (unit entry locks, mobile control of lights and thermostat and leak monitoring) in over 71,000 units across its apartment community portfolio since the initiative began during the first quarter of 2019.

During the fourth quarter of 2022, MAA continued its property repositioning program to upgrade and reposition the amenity and common areas at select apartment communities. The program includes targeted plans to move all units at the properties to higher rents that are expected to deliver yields on cost averaging 8%. During the year ended December 31, 2022, work continued on properties selected for this program in 2021. For the year ended December 31, 2022, MAA spent $19.3 million on this program capturing yields on cost averaging approximately 17% between completed projects and those current projects where properties have begun repricing units to higher rents.

Capital Expenditures

A summary of MAA's capital expenditures and Funds Available for Distribution (FAD) for the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022 and 2021 is set forth below (dollars in millions, except per Share data):

Three months ended | Year ended December 31, | |||||||||||||||

2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | |||||||||||||

Core FFO | $ | 274.7 | $ | 225.2 | $ | 1,008.2 | $ | 830.6 | ||||||||

Recurring capital expenditures | (13.9) | (19.3) | (98.2) | (81.1) | ||||||||||||

Core adjusted FFO (Core AFFO) | 260.8 | 205.9 | 910.0 | 749.5 | ||||||||||||

Redevelopment, revenue enhancing, commercial and other capital | (61.9) | (39.1) | (194.9) | (154.0) | ||||||||||||

FAD | $ | 198.9 | $ | 166.8 | $ | 715.1 | $ | 595.5 | ||||||||

Core FFO per Share - diluted | $ | 2.32 | $ | 1.90 | $ | 8.50 | $ | 7.01 | ||||||||

Core AFFO per Share - diluted | $ | 2.20 | $ | 1.74 | $ | 7.67 | $ | 6.32 | ||||||||

A reconciliation of FFO, Core FFO, Core AFFO and FAD to Net income available for MAA common shareholders, and discussion of the components of FFO, Core FFO, Core AFFO and FAD, can be found later in this release.

Balance Sheet and Financing Activities

As of December 31, 2022, MAA had $1.3 billion of combined cash and available capacity under MAALP's unsecured revolving credit facility.

Dividends and distributions paid on shares of common stock and noncontrolling interests during the fourth quarter of 2022 were $148.3 million, as compared to $121.5 million for the same period in the prior year.

In January 2023, MAA physically settled its two forward sale agreements with respect to a total of 1.1 million shares of its common stock and received net proceeds of approximately $204 million.

Balance sheet highlights as of December 31, 2022 are summarized below (dollars in billions):

Total debt to adjusted | Net Debt/Adjusted | Total debt | Average effective | Fixed rate debt as a % | Total debt average | |||||||||

28.4 % | 3.71x | $ | 4.4 | 3.4 % | 99.5 % | 7.9 | ||||||||

(1) | As defined in the covenants for the bonds issued by MAALP. |

(2) | Adjusted EBITDAre is calculated for the trailing twelve month period ended December 31, 2022. |

A reconciliation of Net Debt to Unsecured notes payable and Secured notes payable and a reconciliation of Adjusted EBITDAre to Net income, along with discussion of the components of Net Debt and Adjusted EBITDAre, can be found later in this release.

ESG

As of the end of 2022, MAA's corporate initiatives have led to significant progress in key social and environmental performance areas. We have achieved a 21.9% reduction in energy use intensity and a 30.8% reduction in GHG emissions intensity from our 2018 baseline, meeting our goal seven years before our original 2028 target, and we believe we are on track to achieve the same in indoor water use intensity. Additionally, we have updated 35% of our portfolio to maximize energy efficiency and now have 25 green-certified communities, with more in the pipeline.

We also have a number of community engagement efforts underway and have reported our progress through our annual Corporate Sustainability Report, CDP disclosure, and GRESB assessment, the latter of which we have now improved year over year since our first submission in 2020. We will continue to focus on deepening engagement, establishing new targets, and building an integrated pathway for ESG, which is an integral component of our continued resiliency and creates a positive impact for our residents, associates, and investors.

116th Consecutive Quarterly Common Dividend Declared

MAA declared its 116th consecutive quarterly common dividend, which was paid on January 31, 2023 to holders of record on January 13, 2023. The current annual dividend rate is $5.60 per common share, an increase of 12% from the immediately prior rate. The timing and amount of future dividends will depend on actual cash flows from operations, MAA's financial condition, capital requirements, the annual distribution requirements under the REIT provisions of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 and other factors as MAA's Board of Directors deems relevant. MAA's Board of Directors may modify the dividend policy from time to time.

2023 Earnings and Same Store Portfolio Guidance

MAA is providing initial 2023 guidance for Net income per diluted common share, Core FFO per Share and Core AFFO per Share, along with its expectations for growth of Property revenue, Property operating expense and NOI for the Same Store Portfolio in 2023. MAA expects to update its 2023 Net income per diluted common share, Core FFO per Share and Core AFFO per Share guidance on a quarterly basis.

FFO, Core FFO and Core AFFO are non-GAAP financial measures. Acquisition and disposition activity materially affects depreciation and capital gains or losses, which combined, generally represent the majority of the difference between Net income available for common shareholders and FFO. As discussed in the definitions of non-GAAP financial measures found later in this release, MAA's definition of FFO is in accordance with the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts', or NAREIT's, definition, and Core FFO represents FFO further adjusted for items that are not considered part of MAA's core business operations. MAA believes that Core FFO is helpful in understanding operating performance in that Core FFO excludes not only depreciation expense of real estate assets and certain other non-routine items, but it also excludes certain items that by their nature are not comparable over periods and therefore tend to obscure actual operating performance.

2023 Guidance | ||

Earnings: | Full Year 2023 | |

Earnings per common share - diluted | $5.97 to $6.37 | |

Core FFO per Share - diluted | $8.88 to $9.28 | |

Core AFFO per Share - diluted | $7.96 to $8.36 | |

MAA Same Store Portfolio: | ||

Property revenue growth | 5.25% to 7.25% | |

Property operating expense growth | 5.15% to 7.15% | |

NOI growth | 5.30% to 7.30% |

MAA expects Core FFO for the first quarter of 2023 to be in the range of $2.14 to $2.30 per Share, or $2.22 per Share at the midpoint. MAA does not forecast Net income per diluted common share on a quarterly basis as MAA generally cannot predict the timing of forecasted acquisition and disposition activity within a particular quarter (rather than during the course of the full year). Additional details and guidance items are provided in the Supplemental Data to this release.

Supplemental Material and Conference Call

Supplemental data to this release can be found on the "For Investors" page of the MAA website at www.maac.com. MAA will host a conference call to further discuss fourth quarter results on February 2, 2023, at 9:00 AM Central Time. The conference call-in number is 877-830-2598. You may also join the live webcast of the conference call by accessing the "For Investors" page of the MAA website at www.maac.com. MAA's filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) are filed under the registrant names of Mid-America Apartment Communities, Inc. and Mid-America Apartments, L.P.

About MAA

MAA, an S&P 500 company, is a real estate investment trust (REIT) focused on delivering full-cycle and superior investment performance for shareholders through the ownership, management, acquisition, development and redevelopment of quality apartment communities primarily in the Southeast, Southwest and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. As of December 31, 2022, MAA had ownership interest in 101,986 apartment units, including communities currently in development, across 16 states and the District of Columbia. For further details, please visit the MAA website at www.maac.com or contact Investor Relations at investor.relations@maac.com, or via mail at MAA, 6815 Poplar Ave., Suite 500, Germantown, TN 38138, Attn: Investor Relations.

Forward-Looking Statements

Sections of this release contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, with respect to our expectations for future periods. Forward-looking statements do not discuss historical fact, but instead include statements related to expectations, projections, intentions or other items related to the future. Such forward-looking statements include, without limitation, statements regarding expected operating performance and results, property stabilizations, property acquisition and disposition activity, joint venture activity, development and renovation activity and other capital expenditures, and capital raising and financing activity, as well as lease pricing, revenue and expense growth, occupancy, interest rate and other economic expectations. Words such as "expects," "anticipates," "intends," "plans," "believes," "seeks," "estimates," "forecasts," "projects," "assumes," "will," "may," "could," "should," "budget," "target," "outlook," "proforma," "opportunity," "guidance" and variations of such words and similar expressions are intended to identify such forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, as described below, which may cause our actual results, performance or achievements to be materially different from the results of operations, financial conditions or plans expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Although we believe that the assumptions underlying the forward-looking statements contained herein are reasonable, any of the assumptions could be inaccurate, and therefore such forward-looking statements included in this release may not prove to be accurate. In light of the significant uncertainties inherent in the forward-looking statements included herein, the inclusion of such information should not be regarded as a representation by us or any other person that the results or conditions described in such statements or our objectives and plans will be achieved.

The following factors, among others, could cause our actual results, performance or achievements to differ materially from those expressed or implied in the forward-looking statements:

- inability to generate sufficient cash flows due to unfavorable economic and market conditions, changes in supply and/or demand, competition, uninsured losses, changes in tax and housing laws, or other factors;

- exposure to risks inherent in investments in a single industry and sector;

- adverse changes in real estate markets, including, but not limited to, the extent of future demand for multifamily units in our significant markets, barriers of entry into new markets which we may seek to enter in the future, limitations on our ability to increase or collect rental rates, competition, our ability to identify and consummate attractive acquisitions or development projects on favorable terms, our ability to consummate any planned dispositions in a timely manner on acceptable terms, and our ability to reinvest sale proceeds in a manner that generates favorable returns;

- failure of development communities to be completed within budget and on a timely basis, if at all, to lease-up as anticipated or to achieve anticipated results;

- unexpected capital needs;

- material changes in operating costs, including real estate taxes, utilities and insurance costs, due to inflation and other factors;

- inability to obtain appropriate insurance coverage at reasonable rates, or at all, or losses from catastrophes in excess of our insurance coverage;

- ability to obtain financing at favorable rates, if at all, or refinance existing debt as it matures;

- level and volatility of interest or capitalization rates or capital market conditions;

- the effect of any rating agency actions on the cost and availability of new debt financing;

- significant change in the mortgage financing market or other factors that would cause single-family housing or other alternative housing options, either as an owned or rental product, to become a more significant competitive product;

- ability to continue to satisfy complex rules in order to maintain our status as a REIT for federal income tax purposes, the ability of MAALP to satisfy the rules to maintain its status as a partnership for federal income tax purposes, the ability of our taxable REIT subsidiaries to maintain their status as such for federal income tax purposes, and our ability and the ability of our subsidiaries to operate effectively within the limitations imposed by these rules;

- inability to attract and retain qualified personnel;

- cyber liability or potential liability for breaches of our or our service providers' information technology systems, or business operations disruptions;

- potential liability for environmental contamination;

- changes in the legal requirements we are subject to, or the imposition of new legal requirements, that adversely affect our operations;

- extreme weather and natural disasters;

- disease outbreaks and other public health events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and measures that are taken by federal, state, and local governmental authorities in response to such outbreaks and events;

- impact of climate change on our properties or operations;

- legal proceedings or class action lawsuits;

- impact of reputational harm caused by negative press or social media postings of our actions or policies, whether or not warranted;

- compliance costs associated with numerous federal, state and local laws and regulations; and

- other risks identified in this release and in reports we file with the SEC or in other documents that we publicly disseminate.

New factors may also emerge from time to time that could have a material adverse effect on our business. Except as required by law, we undertake no obligation to publicly update or revise forward-looking statements contained in this release to reflect events, circumstances or changes in expectations after the date of this release.

FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS | ||||||||||||||||

Dollars in thousands, except per share data | Three months ended December 31, | Year ended December 31, | ||||||||||||||

2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | |||||||||||||

Rental and other property revenues | $ | 527,965 | $ | 463,575 | $ | 2,019,866 | $ | 1,778,082 | ||||||||

Net income available for MAA common shareholders | $ | 192,699 | $ | 184,719 | $ | 633,748 | $ | 530,103 | ||||||||

Total NOI (1) | $ | 346,791 | $ | 296,477 | $ | 1,296,172 | $ | 1,106,917 | ||||||||

Earnings per common share: (2) | ||||||||||||||||

Basic | $ | 1.67 | $ | 1.60 | $ | 5.49 | $ | 4.62 | ||||||||

Diluted | $ | 1.67 | $ | 1.60 | $ | 5.48 | $ | 4.61 | ||||||||

Funds from operations per Share - diluted: (2) | ||||||||||||||||

FFO (1) | $ | 2.12 | $ | 2.01 | $ | 8.20 | $ | 7.20 | ||||||||

Core FFO (1) | $ | 2.32 | $ | 1.90 | $ | 8.50 | $ | 7.01 | ||||||||

Core AFFO (1) | $ | 2.20 | $ | 1.74 | $ | 7.67 | $ | 6.32 | ||||||||

Dividends declared per common share | $ | 1.4000 | $ | 1.0875 | $ | 4.9875 | $ | 4.1625 | ||||||||

Dividends/Core FFO (diluted) payout ratio | 60.3 | % | 57.2 | % | 58.7 | % | 59.4 | % | ||||||||

Dividends/Core AFFO (diluted) payout ratio | 63.6 | % | 62.5 | % | 65.0 | % | 65.9 | % | ||||||||

Consolidated interest expense | $ | 38,084 | $ | 39,108 | $ | 154,747 | $ | 156,881 | ||||||||

Mark-to-market debt adjustment | 13 | (36) | (77) | (270) | ||||||||||||

Debt discount and debt issuance cost amortization | (1,528) | (1,474) | (5,985) | (5,383) | ||||||||||||

Capitalized interest | 2,582 | 1,939 | 8,728 | 9,720 | ||||||||||||

Total interest incurred | $ | 39,151 | $ | 39,537 | $ | 157,413 | $ | 160,948 | ||||||||

Amortization of principal on notes payable | $ | 358 | $ | 337 | $ | 1,401 | $ | 1,516 | ||||||||

(1) | A reconciliation of the following items and discussion of their respective components can be found later in this release: (i) NOI to Net income available for MAA common shareholders; and (ii) FFO, Core FFO and Core AFFO to Net income available for MAA common shareholders. |

(2) | See the "Share and Unit Data" section for additional information. |

Dollars in thousands, except share price | ||||||||

December 31, 2022 | December 31, 2021 | |||||||

Gross Assets (1) | $ | 15,543,912 | $ | 15,133,343 | ||||

Gross Real Estate Assets (1) | $ | 15,336,793 | $ | 14,865,818 | ||||

Total debt | $ | 4,414,903 | $ | 4,516,690 | ||||

Common shares and units outstanding | 118,645,269 | 118,542,994 | ||||||

Share price | $ | 156.99 | $ | 229.44 | ||||

Book equity value | $ | 6,210,419 | $ | 6,184,092 | ||||

Market equity value | $ | 18,626,121 | $ | 27,198,505 | ||||

Net Debt/Adjusted EBITDAre (2) | 3.71x | 4.39x | ||||||

(1) | A reconciliation of Gross Assets to Total assets and Gross Real Estate Assets to Real estate assets, net, along with discussion of their components, can be found later in this release. |

(2) | Adjusted EBITDAre is calculated for the trailing twelve month period for each date presented. A reconciliation of the following items and discussion of their respective components can be found later in this release: (i) Net Debt to Unsecured notes payable and Secured notes payable; and (ii) EBITDA, EBITDAre and Adjusted EBITDAre to Net income. |

CONSOLIDATED STATEMENTS OF OPERATIONS | ||||||||||||||||

Dollars in thousands, except per share data (Unaudited) | Three months ended | Year ended December 31, | ||||||||||||||

2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | |||||||||||||

Revenues: | ||||||||||||||||

Rental and other property revenues | $ | 527,965 | $ | 463,575 | $ | 2,019,866 | $ | 1,778,082 | ||||||||

Expenses: | ||||||||||||||||

Operating expenses, excluding real estate taxes and insurance | 106,594 | 100,164 | 435,108 | 404,288 | ||||||||||||

Real estate taxes and insurance | 74,580 | 66,934 | 288,586 | 266,877 | ||||||||||||

Depreciation and amortization | 138,237 | 135,495 | 542,998 | 533,433 | ||||||||||||

Total property operating expenses | 319,411 | 302,593 | 1,266,692 | 1,204,598 | ||||||||||||

Property management expenses | 17,034 | 15,210 | 65,463 | 55,732 | ||||||||||||

General and administrative expenses | 14,742 | 14,121 | 58,833 | 52,884 | ||||||||||||

Interest expense | 38,084 | 39,108 | 154,747 | 156,881 | ||||||||||||

Gain on sale of depreciable real estate assets | (82,799) | (85,913) | (214,762) | (220,428) | ||||||||||||

Gain on sale of non-depreciable real estate assets | — | (609) | (809) | (811) | ||||||||||||

Other non-operating expense (income) | 23,465 | (19,345) | 42,713 | (33,902) | ||||||||||||

Income before income tax expense | 198,028 | 198,410 | 646,989 | 563,128 | ||||||||||||

Income tax benefit (expense) | 458 | (7,790) | 6,208 | (13,637) | ||||||||||||

Income from continuing operations before real estate joint venture activity | 198,486 | 190,620 | 653,197 | 549,491 | ||||||||||||

Income from real estate joint venture | 450 | 296 | 1,579 | 1,211 | ||||||||||||

Net income | 198,936 | 190,916 | 654,776 | 550,702 | ||||||||||||

Net income attributable to noncontrolling interests | 5,315 | 5,275 | 17,340 | 16,911 | ||||||||||||

Net income available for shareholders | 193,621 | 185,641 | 637,436 | 533,791 | ||||||||||||

Dividends to MAA Series I preferred shareholders | 922 | 922 | 3,688 | 3,688 | ||||||||||||

Net income available for MAA common shareholders | $ | 192,699 | $ | 184,719 | $ | 633,748 | $ | 530,103 | ||||||||

Earnings per common share - basic: | ||||||||||||||||

Net income available for common shareholders | $ | 1.67 | $ | 1.60 | $ | 5.49 | $ | 4.62 | ||||||||

Earnings per common share - diluted: | ||||||||||||||||

Net income available for common shareholders | $ | 1.67 | $ | 1.60 | $ | 5.48 | $ | 4.61 | ||||||||

SHARE AND UNIT DATA | ||||||||||||||||

Shares and units in thousands | Three months ended December 31, | Year ended December 31, | ||||||||||||||

2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | |||||||||||||

Net Income Shares (1) | ||||||||||||||||

Weighted average common shares - basic | 115,398 | 115,158 | 115,344 | 114,717 | ||||||||||||

Effect of dilutive securities | 251 | 458 | 239 | 322 | ||||||||||||

Weighted average common shares - diluted | 115,649 | 115,616 | 115,583 | 115,039 | ||||||||||||

Funds From Operations Shares And Units | ||||||||||||||||

Weighted average common shares and units - basic | 118,568 | 118,433 | 118,538 | 118,400 | ||||||||||||

Weighted average common shares and units - diluted | 118,646 | 118,637 | 118,618 | 118,519 | ||||||||||||

Period End Shares And Units | ||||||||||||||||

Common shares at December 31, | 115,480 | 115,337 | 115,480 | 115,337 | ||||||||||||

Operating Partnership units at December 31, | 3,165 | 3,206 | 3,165 | 3,206 | ||||||||||||

Total common shares and units at December 31, | 118,645 | 118,543 | 118,645 | 118,543 | ||||||||||||

(1) | For additional information on the calculation of diluted common shares and earnings per common share, please refer to the Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements in MAA's Annual Report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2022, expected to be filed with the SEC on or about February 16, 2023. |

CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEETS | ||||||||

Dollars in thousands (Unaudited) | ||||||||

December 31, 2022 | December 31, 2021 | |||||||

Assets | ||||||||

Real estate assets: | ||||||||

Land | $ | 2,008,364 | $ | 1,977,813 | ||||

Buildings and improvements and other | 12,841,947 | 12,454,439 | ||||||

Development and capital improvements in progress | 332,035 | 247,970 | ||||||

15,182,346 | 14,680,222 | |||||||

Less: Accumulated depreciation | (4,302,747) | (3,848,161) | ||||||

10,879,599 | 10,832,061 | |||||||

Undeveloped land | 64,312 | 24,015 | ||||||

Investment in real estate joint venture | 42,290 | 42,827 | ||||||

Real estate assets, net | 10,986,201 | 10,898,903 | ||||||

Cash and cash equivalents | 38,659 | 54,302 | ||||||

Restricted cash | 22,412 | 76,296 | ||||||

Other assets | 193,893 | 255,681 | ||||||

Total assets | 11,241,165 | 11,285,182 | ||||||

Liabilities and equity | ||||||||

Liabilities: | ||||||||

Unsecured notes payable | $ | 4,050,910 | $ | 4,151,375 | ||||

Secured notes payable | 363,993 | 365,315 | ||||||

Accrued expenses and other liabilities | 615,843 | 584,400 | ||||||

Total liabilities | 5,030,746 | 5,101,090 | ||||||

Redeemable common stock | 20,671 | 30,185 | ||||||

Shareholders' equity: | ||||||||

Preferred stock | 9 | 9 | ||||||

Common stock | 1,152 | 1,151 | ||||||

Additional paid-in capital | 7,202,834 | 7,230,956 | ||||||

Accumulated distributions in excess of net income | (1,188,854) | (1,255,807) | ||||||

Accumulated other comprehensive loss | (10,052) | (11,132) | ||||||

Total MAA shareholders' equity | 6,005,089 | 5,965,177 | ||||||

Noncontrolling interests - Operating Partnership units | 163,595 | 165,116 | ||||||

Total Company's shareholders' equity | 6,168,684 | 6,130,293 | ||||||

Noncontrolling interests - consolidated real estate entities | 21,064 | 23,614 | ||||||

Total equity | 6,189,748 | 6,153,907 | ||||||

Total liabilities and equity | $ | 11,241,165 | $ | 11,285,182 | ||||

RECONCILIATION OF FFO, CORE FFO, CORE AFFO AND FAD TO NET INCOME AVAILABLE FOR MAA COMMON SHAREHOLDERS | ||||||||||||||||

Amounts in thousands, except per share and unit data | Three months ended December 31, | Year ended December 31, | ||||||||||||||

2022 | 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | |||||||||||||

Net income available for MAA common shareholders | $ | 192,699 | $ | 184,719 | $ | 633,748 | $ | 530,103 | ||||||||

Depreciation and amortization of real estate assets | 136,469 | 133,634 | 535,835 | 526,220 | ||||||||||||

Gain on sale of depreciable real estate assets | (82,799) | (85,913) | (214,762) | (220,428) | ||||||||||||

Depreciation and amortization of real estate assets of real estate | 155 | 153 | 621 | 616 | ||||||||||||

Net income attributable to noncontrolling interests | 5,315 | 5,275 | 17,340 | 16,911 | ||||||||||||

FFO attributable to the Company | 251,839 | 237,868 | 972,782 | 853,422 | ||||||||||||

Loss on embedded derivative in preferred shares (1) | 10,743 | 16,052 | 21,107 | 4,560 | ||||||||||||

Gain on sale of non-depreciable real estate assets | — | (609) | (809) | (811) | ||||||||||||

Loss (gain) on investments, net of tax (1)(2) | 4,786 | (26,644) | 35,822 | (40,875) | ||||||||||||

Casualty related (recoveries) charges, net (3) | (759) | (480) | (29,930) | 1,524 | ||||||||||||

Loss on debt extinguishment (1) | — | — | 47 | 13,391 | ||||||||||||

Legal costs and settlements, net (1) | 8,000 | (1,451) | 8,535 | (2,167) | ||||||||||||

COVID-19 related costs (1) | 73 | 390 | 575 | 1,301 | ||||||||||||

Mark-to-market debt adjustment (4) | (13) | 36 | 77 | 270 | ||||||||||||

Core FFO | 274,669 | 225,162 | 1,008,206 | 830,615 | ||||||||||||

Recurring capital expenditures | (13,825) | (19,297) | (98,168) | (81,106) | ||||||||||||

Core AFFO | 260,844 | 205,865 | 910,038 | 749,509 | ||||||||||||

Redevelopment capital expenditures | (23,755) | (15,835) | (101,035) | (85,467) | ||||||||||||

Revenue enhancing capital expenditures | (26,472) | (13,645) | (65,572) | (43,133) | ||||||||||||

Commercial capital expenditures | (1,938) | (1,539) | (4,692) | (3,842) | ||||||||||||

Other capital expenditures (5) | (9,822) | (8,086) | (23,595) | (21,561) | ||||||||||||

FAD | $ | 198,857 | $ | 166,760 | $ | 715,144 | $ | 595,506 | ||||||||

Dividends and distributions paid | $ | 148,306 | $ | 121,505 | $ | 554,532 | $ | 485,898 | ||||||||

Weighted average common shares - diluted | 115,649 | 115,616 | 115,583 | 115,039 | ||||||||||||

FFO weighted average common shares and units - diluted | 118,646 | 118,637 | 118,618 | 118,519 | ||||||||||||

Earnings per common share - diluted: | ||||||||||||||||

Net income available for common shareholders | $ | 1.67 | $ | 1.60 | $ | 5.48 | $ | 4.61 | ||||||||

FFO per Share - diluted | $ | 2.12 | $ | 2.01 | $ | 8.20 | $ | 7.20 | ||||||||

Core FFO per Share - diluted | $ | 2.32 | $ | 1.90 | $ | 8.50 | $ | 7.01 | ||||||||

Core AFFO per Share - diluted | $ | 2.20 | $ | 1.74 | $ | 7.67 | $ | 6.32 | ||||||||

(1) | Included in Other non-operating expense (income) in the Consolidated Statements of Operations. |

(2) | For the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022, loss (gain) on investments are presented net of tax benefit of $1.3 million and $9.5 million, respectively. For the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2021, loss (gain) on investments are presented net of tax expense of $7.1 million and $10.8 million, respectively. |

(3) | For the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022, MAA incurred $5.8 million in casualty losses related to winter storm Elliot (primarily building repairs, landscaping and asset write-offs). During the year ended December 31, 2021, MAA incurred $26.0 million in casualty losses related to winter storm Uri. The majority of the storm costs are expected to be or have been reimbursed through insurance coverage. An insurance recovery was recognized in Other non-operating expense (income) in the amount of the recognized losses that MAA expects to recover. Additional costs related to the storms that are not expected to be recovered through insurance coverage, along with other unrelated casualty losses and recoveries, including the receipt of insurance proceeds that exceeded its recorded casualty losses from winter storm Uri, are reflected in Casualty related (recoveries) charges, net. For the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022, MAA recognized a gain of $1.4 million and $29.0 million, respectively, from the receipt of insurance proceeds that exceeded its casualty losses related to winter storm Uri. These adjustments are primarily included in Other non-operating expense (income). |

(4) | Included in Interest expense in the Consolidated Statements of Operations. |

(5) | For the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022, $1.1 million and $3.1 million, respectively, of corporate related capital expenditures are excluded from other capital expenditures. For the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2021, $12.7 million and $44.5 million, respectively, of reconstruction-related capital expenditures relating to winter storm Uri and corporate related capital expenditures are excluded from other capital expenditures. The capital expenditures relating to winter storm Uri have been reimbursed through insurance coverage. |

RECONCILIATION OF NET OPERATING INCOME TO NET INCOME AVAILABLE FOR MAA COMMON SHAREHOLDERS | ||||||||||||||||||||

Dollars in thousands | Three Months Ended | Year Ended | ||||||||||||||||||

December 31, | September 30, | December 31, | December 31, | December 31, | ||||||||||||||||

Net Operating Income | ||||||||||||||||||||

Same Store NOI | $ | 332,199 | $ | 315,616 | $ | 284,425 | $ | 1,242,695 | $ | 1,061,572 | ||||||||||

Non-Same Store and Other NOI | 14,592 | 13,744 | 12,052 | 53,477 | 45,345 | |||||||||||||||

Total NOI | 346,791 | 329,360 | 296,477 | 1,296,172 | 1,106,917 | |||||||||||||||

Depreciation and amortization | (138,237) | (136,879) | (135,495) | (542,998) | (533,433) | |||||||||||||||

Property management expenses | (17,034) | (16,262) | (15,210) | (65,463) | (55,732) | |||||||||||||||

General and administrative expenses | (14,742) | (12,188) | (14,121) | (58,833) | (52,884) | |||||||||||||||

Interest expense | (38,084) | (38,637) | (39,108) | (154,747) | (156,881) | |||||||||||||||

Gain (loss) on sale of depreciable real estate | 82,799 | (1) | 85,913 | 214,762 | 220,428 | |||||||||||||||

Gain on sale of non-depreciable real estate | — | 431 | 609 | 809 | 811 | |||||||||||||||

Other non-operating (expense) income | (23,465) | (1,718) | 19,345 | (42,713) | 33,902 | |||||||||||||||

Income tax benefit (expense) | 458 | 1,256 | (7,790) | 6,208 | (13,637) | |||||||||||||||

Income from real estate joint venture | 450 | 341 | 296 | 1,579 | 1,211 | |||||||||||||||

Net income attributable to noncontrolling | (5,315) | (3,392) | (5,275) | (17,340) | (16,911) | |||||||||||||||

Dividends to MAA Series I preferred | (922) | (922) | (922) | (3,688) | (3,688) | |||||||||||||||

Net income available for MAA common | $ | 192,699 | $ | 121,389 | $ | 184,719 | $ | 633,748 | $ | 530,103 | ||||||||||

RECONCILIATION OF EBITDA, EBITDAre AND ADJUSTED EBITDAre TO NET INCOME | ||||||||||||||||

Dollars in thousands | Three Months Ended | Year Ended | ||||||||||||||

December 31, | December 31, | December 31, | December 31, | |||||||||||||

Net income | $ | 198,936 | $ | 190,916 | $ | 654,776 | $ | 550,702 | ||||||||

Depreciation and amortization | 138,237 | 135,495 | 542,998 | 533,433 | ||||||||||||

Interest expense | 38,084 | 39,108 | 154,747 | 156,881 | ||||||||||||

Income tax (benefit) expense | (458) | 7,790 | (6,208) | 13,637 | ||||||||||||

EBITDA | 374,799 | 373,309 | 1,346,313 | 1,254,653 | ||||||||||||

Gain on sale of depreciable real estate assets | (82,799) | (85,913) | (214,762) | (220,428) | ||||||||||||

Adjustments to reflect the Company's share of | 338 | 338 | 1,357 | 1,352 | ||||||||||||

EBITDAre | 292,338 | 287,734 | 1,132,908 | 1,035,577 | ||||||||||||

Loss on embedded derivative in preferred shares (1) | 10,743 | 16,052 | 21,107 | 4,560 | ||||||||||||

Gain on sale of non-depreciable real estate assets | — | (609) | (809) | (811) | ||||||||||||

Loss (gain) on investments (1) | 6,068 | (33,713) | 45,357 | (51,714) | ||||||||||||

Casualty related (recoveries) charges, net (2) | (759) | (480) | (29,930) | 1,524 | ||||||||||||

Loss on debt extinguishment (1) | — | — | 47 | 13,391 | ||||||||||||

Legal costs and settlements, net (1) | 8,000 | (1,451) | 8,535 | (2,167) | ||||||||||||

COVID-19 related costs (1) | 73 | 390 | 575 | 1,301 | ||||||||||||

Adjusted EBITDAre | $ | 316,463 | $ | 267,923 | $ | 1,177,790 | $ | 1,001,661 | ||||||||

(1) | Included in Other non-operating expense (income) in the Consolidated Statements of Operations. |

(2) | For the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022, MAA incurred $5.8 million in casualty losses related to winter storm Elliot (primarily building repairs, landscaping and asset write-offs). During the year ended December 31, 2021, MAA incurred $26.0 million in casualty losses related to winter storm Uri. The majority of the storm costs are expected to be or have been reimbursed through insurance coverage. An insurance recovery was recognized in Other non-operating expense (income) in the amount of the recognized losses that MAA expects to recover. Additional costs related to the storms that are not expected to be recovered through insurance coverage, along with other unrelated casualty losses and recoveries, including the receipt of insurance proceeds that exceeded its recorded casualty losses from winter storm Uri, are reflected in Casualty related (recoveries) charges, net. For the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022, MAA recognized a gain of $1.4 million and $29.0 million, respectively, from the receipt of insurance proceeds that exceeded its casualty losses related to winter storm Uri. These adjustments are primarily included in Other non-operating expense (income). |

RECONCILIATION OF NET DEBT TO UNSECURED NOTES PAYABLE AND SECURED NOTES PAYABLE | ||||||||

Dollars in thousands | ||||||||

December 31, 2022 | December 31, 2021 | |||||||

Unsecured notes payable | $ | 4,050,910 | $ | 4,151,375 | ||||

Secured notes payable | 363,993 | 365,315 | ||||||

Total debt | 4,414,903 | 4,516,690 | ||||||

Cash and cash equivalents | (38,659) | (54,302) | ||||||

1031(b) exchange proceeds included in Restricted cash (1) | (9,186) | (64,452) | ||||||

Net Debt | $ | 4,367,058 | $ | 4,397,936 | ||||

(1) | Included in Restricted cash in the Consolidated Balance Sheets. |

RECONCILIATION OF GROSS ASSETS TO TOTAL ASSETS | ||||||||

Dollars in thousands | ||||||||

December 31, 2022 | December 31, 2021 | |||||||

Total assets | $ | 11,241,165 | $ | 11,285,182 | ||||

Accumulated depreciation | 4,302,747 | 3,848,161 | ||||||

Gross Assets | $ | 15,543,912 | $ | 15,133,343 | ||||

RECONCILIATION OF GROSS REAL ESTATE ASSETS TO REAL ESTATE ASSETS, NET | ||||||||

Dollars in thousands | ||||||||

December 31, 2022 | December 31, 2021 | |||||||

Real estate assets, net | $ | 10,986,201 | $ | 10,898,903 | ||||

Accumulated depreciation | 4,302,747 | 3,848,161 | ||||||

Cash and cash equivalents | 38,659 | 54,302 | ||||||

1031(b) exchange proceeds included in Restricted cash (1) | 9,186 | 64,452 | ||||||

Gross Real Estate Assets | $ | 15,336,793 | $ | 14,865,818 | ||||

(1) | Included in Restricted cash in the Consolidated Balance Sheets. |

NON-GAAP FINANCIAL MEASURES

Adjusted EBITDAre

For purposes of calculations in this release, Adjusted Earnings Before Interest, Income Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization for real estate, or Adjusted EBITDAre, represents EBITDAre further adjusted for items that are not considered part of MAA's core operations such as adjustments related to the fair value of the embedded derivative in the MAA Series I preferred shares, gain or loss on sale of non-depreciable assets, gain or loss on investments, casualty related (recoveries) charges, net, gain or loss on debt extinguishment, legal costs and settlements, net and COVID-19 related costs. As an owner and operator of real estate, MAA considers Adjusted EBITDAre to be an important measure of performance from core operations because Adjusted EBITDAre does not include various income and expense items that are not indicative of operating performance. MAA's computation of Adjusted EBITDAre may differ from the methodology utilized by other companies to calculate Adjusted EBITDAre. Adjusted EBITDAre should not be considered as an alternative to Net income as an indicator of operating performance.

Core Adjusted Funds from Operations (Core AFFO)

Core AFFO is composed of Core FFO less recurring capital expenditures. Core AFFO should not be considered as an alternative to Net income available for MAA common shareholders as an indicator of operating performance. As an owner and operator of real estate, MAA considers Core AFFO to be an important measure of performance from operations because Core AFFO measures the ability to control revenues, expenses and recurring capital expenditures.

Core Funds from Operations (Core FFO)

Core FFO represents FFO as adjusted for items that are not considered part of MAA's core business operations such as adjustments related to the fair value of the embedded derivative in the MAA Series I preferred shares, gain or loss on sale of non-depreciable assets, gain or loss on investments, net of tax, casualty related (recoveries) charges, net, gain or loss on debt extinguishment, legal costs and settlements, net, COVID-19 related costs, mark-to-market debt adjustments and other non-core items. While MAA's definition of Core FFO may be similar to others in the industry, MAA's methodology for calculating Core FFO may differ from that utilized by other REITs and, accordingly, may not be comparable to such other REITs. Core FFO should not be considered as an alternative to Net income available for MAA common shareholders as an indicator of operating performance. MAA believes that Core FFO is helpful in understanding its core operating performance between periods in that it removes certain items that by their nature are not comparable over periods and therefore tend to obscure actual operating performance.

EBITDA

For purposes of calculations in this release, Earnings Before Interest, Income Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization, or EBITDA, is composed of net income plus depreciation and amortization, interest expense, and income taxes. As an owner and operator of real estate, MAA considers EBITDA to be an important measure of performance from core operations because EBITDA does not include various expense items that are not indicative of operating performance. EBITDA should not be considered as an alternative to Net income as an indicator of operating performance.

EBITDAre

For purposes of calculations in this release, Earnings Before Interest, Income Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization for real estate, or EBITDAre, is composed of EBITDA further adjusted for the gain or loss on sale of depreciable asset sales and adjustments to reflect MAA's share of EBITDAre of unconsolidated affiliates. As an owner and operator of real estate, MAA considers EBITDAre to be an important measure of performance from core operations because EBITDAre does not include various expense items that are not indicative of operating performance. While MAA's definition of EBITDAre is in accordance with NAREIT's definition, it may differ from the methodology utilized by other companies to calculate EBITDAre. EBITDAre should not be considered as an alternative to Net income as an indicator of operating performance.

Funds Available for Distribution (FAD)

FAD is composed of Core FFO less total capital expenditures, excluding development spending, property acquisitions, capital expenditures relating to significant casualty losses that management expects to be reimbursed by insurance proceeds and corporate related capital expenditures. FAD should not be considered as an alternative to Net income available for MAA common shareholders as an indicator of operating performance. As an owner and operator of real estate, MAA considers FAD to be an important measure of performance from core operations because FAD measures the ability to control revenues, expenses and capital expenditures.

Funds From Operations (FFO)

FFO represents net income available for MAA common shareholders (calculated in accordance with GAAP) excluding gain or loss on disposition of operating properties and asset impairment, plus depreciation and amortization of real estate assets, net income attributable to noncontrolling interests, and adjustments for joint ventures. Because net income attributable to noncontrolling interests is added back, FFO, when used in this document, represents FFO attributable to the Company. While MAA's definition of FFO is in accordance with NAREIT's definition, it may differ from the methodology for calculating FFO utilized by other companies and, accordingly, may not be comparable to such other companies. FFO should not be considered as an alternative to Net income available for MAA common shareholders as an indicator of operating performance. MAA believes that FFO is helpful in understanding operating performance in that FFO excludes depreciation and amortization of real estate assets. MAA believes that GAAP historical cost depreciation of real estate assets is generally not correlated with changes in the value of those assets, whose value does not diminish predictably over time, as historical cost depreciation implies.

Gross Assets

Gross Assets represents Total assets plus Accumulated depreciation. MAA believes that Gross Assets can be used as a helpful tool in evaluating its balance sheet positions. MAA believes that GAAP historical cost depreciation of real estate assets is generally not correlated with changes in the value of those assets, whose value does not diminish predictably over time, as historical cost depreciation implies.

Gross Real Estate Assets

Gross Real Estate Assets represents Real estate assets, net plus Accumulated depreciation, Cash and cash equivalents and 1031(b) exchange proceeds included in Restricted cash. MAA believes that Gross Real Estate Assets can be used as a helpful tool in evaluating its balance sheet positions. MAA believes that GAAP historical cost depreciation of real estate assets is generally not correlated with changes in the value of those assets, whose value does not diminish predictably over time, as historical cost depreciation implies.

Net Debt

Net Debt represents Unsecured notes payable and Secured notes payable less Cash and cash equivalents and 1031(b) exchange proceeds included in Restricted cash. MAA believes Net Debt is a helpful tool in evaluating its debt position.

Net Operating Income (NOI)

Net Operating Income represents Rental and other property revenues less Total property operating expenses, excluding depreciation and amortization, for all properties held during the period, regardless of their status as held for sale. NOI should not be considered as an alternative to Net income available for MAA common shareholders. MAA believes NOI is a helpful tool in evaluating operating performance because it measures the core operations of property performance by excluding corporate level expenses and other items not related to property operating performance.

Non-Same Store and Other NOI

Non-Same Store and Other NOI represents Rental and other property revenues less Total property operating expenses, excluding depreciation and amortization, for all properties classified within the Non-Same Store and Other Portfolio during the period. Non-Same Store and Other NOI includes all storm-related expenses related to hurricanes. Non-Same Store and Other NOI should not be considered as an alternative to Net income available for MAA common shareholders. MAA believes Non-Same Store and Other NOI is a helpful tool in evaluating operating performance because it measures the core operations of property performance by excluding corporate level expenses and other items not related to property operating performance.

Same Store NOI

Same Store NOI represents Rental and other property revenues less Total property operating expenses, excluding depreciation and amortization, for all properties classified within the Same Store Portfolio during the period. Same Store NOI excludes storm-related expenses related to hurricanes. Same Store NOI should not be considered as an alternative to Net income available for MAA common shareholders. MAA believes Same Store NOI is a helpful tool in evaluating operating performance because it measures the core operations of property performance by excluding corporate level expenses and other items not related to property operating performance.

OTHER KEY DEFINITIONS

Average Effective Rent per Unit

Average Effective Rent per Unit represents the average of gross rent amounts after the effect of leasing concessions for occupied units plus prevalent market rates asked for unoccupied units, divided by the total number of units. Leasing concessions represent discounts to the current market rate. MAA believes average effective rent is a helpful measurement in evaluating average pricing. It does not represent actual rental revenue collected per unit.

Average Physical Occupancy

Average Physical Occupancy represents the average of the daily physical occupancy for an applicable period.

Development Communities

Communities remain identified as development until certificates of occupancy are obtained for all units under development. Once all units are delivered and available for occupancy, the community moves into the Lease-up Communities portfolio.

Lease-up Communities

New acquisitions acquired during lease-up and newly developed communities remain in the Lease-up Communities portfolio until stabilized. Communities are considered stabilized when achieving 90% average physical occupancy for 90 days.

Non-Same Store and Other Portfolio

Non-Same Store and Other Portfolio includes recently acquired communities, communities in development or lease-up, communities that have been disposed of or identified for disposition, communities that have experienced a significant casualty loss, stabilized communities that do not meet the requirements defined by the Same Store Portfolio, retail properties and commercial properties.

Resident Turnover

Resident turnover represents resident move outs excluding transfers within the Same Store Portfolio as a percentage of expiring leases on a rolling twelve month basis as of the end of the reported quarter.

Same Store Portfolio

MAA reviews its Same Store Portfolio at the beginning of each calendar year, or as significant transactions or events warrant. Communities are generally added into the Same Store Portfolio if they were owned and stabilized at the beginning of the previous year. Communities are considered stabilized when achieving 90% average physical occupancy for 90 days. Communities that have been approved by MAA's Board of Directors for disposition are excluded from the Same Store Portfolio. Communities that have experienced a significant casualty loss are also excluded from the Same Store Portfolio.

View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/maa-reports-fourth-quarter-and-full-year-2022-results-301736655.html

SOURCE MAA

Uncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

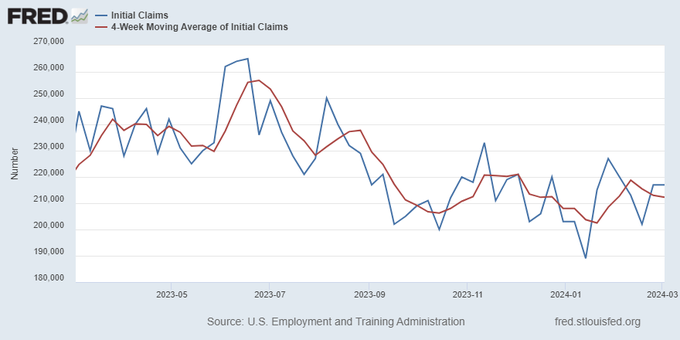

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

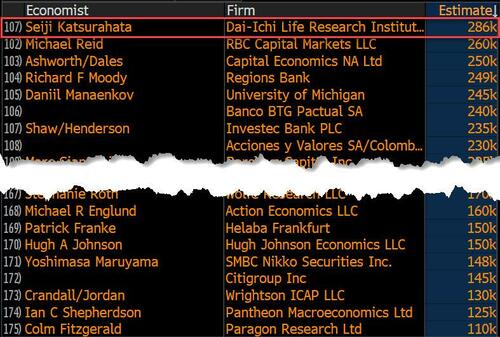

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

Uncategorized

Economic Earthquake Ahead? The Cracks Are Spreading Fast

Economic Earthquake Ahead? The Cracks Are Spreading Fast

Authored by Brandon Smith via Alt-Market.us,

One of my favorite false narratives…

Authored by Brandon Smith via Alt-Market.us,

One of my favorite false narratives floating around corporate media platforms has been the argument that the American people “just don’t seem to understand how good the economy really is right now.” If only they would look at the stats, they would realize that we are in the middle of a financial renaissance, right? It must be that people have been brainwashed by negative press from conservative sources…

I have to laugh at this notion because it’s a very common one throughout history – it’s an assertion made by almost every single political regime right before a major collapse. These people always say the same things, and when you study economics as long as I have you can’t help but throw up your hands and marvel at their dedication to the propaganda.

One example that comes to mind immediately is the delusional optimism of the “roaring” 1920s and the lead up to the Great Depression. At the time around 60% of the U.S. population was living in poverty conditions (according to the metrics of the decade) earning less than $2000 a year. However, in the years after WWI ravaged Europe, America’s economic power was considered unrivaled.

The 1920s was an era of mass production and rampant consumerism but it was all fueled by easy access to debt, a condition which had not really existed before in America. It was this illusion of prosperity created by the unchecked application of credit that eventually led to the massive stock market bubble and the crash of 1929. This implosion, along with the Federal Reserve’s policy of raising interest rates into economic weakness, created a black hole in the U.S. financial system for over a decade.

There are two primary tools that various failing regimes will often use to distort the true conditions of the economy: Debt and inflation. In the case of America today, we are experiencing BOTH problems simultaneously and this has made certain economic indicators appear healthy when they are, in fact, highly unstable. The average American knows this is the case because they see the effects everyday. They see the damage to their wallets, to their buying power, in the jobs market and in their quality of life. This is why public faith in the economy has been stuck in the dregs since 2021.

The establishment can flash out-of-context stats in people’s faces, but they can’t force the populace to see a recovery that simply does not exist. Let’s go through a short list of the most faulty indicators and the real reasons why the fiscal picture is not a rosy as the media would like us to believe…

The “miracle” labor market recovery

In the case of the U.S. labor market, we have a clear example of distortion through inflation. The $8 trillion+ dropped on the economy in the first 18 months of the pandemic response sent the system over the edge into stagflation land. Helicopter money has a habit of doing two things very well: Blowing up a bubble in stock markets and blowing up a bubble in retail. Hence, the massive rush by Americans to go out and buy, followed by the sudden labor shortage and the race to hire (mostly for low wage part-time jobs).

The problem with this “miracle” is that inflation leads to price explosions, which we have already experienced. The average American is spending around 30% more for goods, services and housing compared to what they were spending in 2020. This is what happens when you have too much money chasing too few goods and limited production.

The jobs market looks great on paper, but the majority of jobs generated in the past few years are jobs that returned after the covid lockdowns ended. The rest are jobs created through monetary stimulus and the artificial retail rush. Part time low wage service sector jobs are not going to keep the country rolling for very long in a stagflation environment. The question is, what happens now that the stimulus punch bowl has been removed?

Just as we witnessed in the 1920s, Americans have turned to debt to make up for higher prices and stagnant wages by maxing out their credit cards. With the central bank keeping interest rates high, the credit safety net will soon falter. This condition also goes for businesses; the same businesses that will jump headlong into mass layoffs when they realize the party is over. It happened during the Great Depression and it will happen again today.

Cracks in the foundation

We saw cracks in the narrative of the financial structure in 2023 with the banking crisis, and without the Federal Reserve backstop policy many more small and medium banks would have dropped dead. The weakness of U.S. banks is offset by the relative strength of the U.S. dollar, which lures in foreign investors hoping to protect their wealth using dollar denominated assets.

But something is amiss. Gold and bitcoin have rocketed higher along with economically sensitive assets and the dollar. This is the opposite of what’s supposed to happen. Gold and BTC are supposed to be hedges against a weak dollar and a weak economy, right? If global faith in the dollar and in the U.S. economy is so high, why are investors diving into protective assets like gold?

Again, as noted above, inflation distorts everything.

Tens of trillions of extra dollars printed by the Fed are floating around and it’s no surprise that much of that cash is flooding into the economy which simply pushes higher right along with prices on the shelf. But, gold and bitcoin are telling us a more honest story about what’s really happening.

Right now, the U.S. government is adding around $600 billion per month to the national debt as the Fed holds rates higher to fight inflation. This debt is going to crush America’s financial standing for global investors who will eventually ask HOW the U.S. is going to handle that growing millstone? As I predicted years ago, the Fed has created a perfect Catch-22 scenario in which the U.S. must either return to rampant inflation, or, face a debt crisis. In either case, U.S. dollar-denominated assets will lose their appeal and their prices will plummet.

“Healthy” GDP is a complete farce

GDP is the most common out-of-context stat used by governments to convince the citizenry that all is well. It is yet another stat that is entirely manipulated by inflation. It is also manipulated by the way in which modern governments define “economic activity.”

GDP is primarily driven by spending. Meaning, the higher inflation goes, the higher prices go, and the higher GDP climbs (to a point). Eventually prices go too high, credit cards tap out and spending ceases. But, for a short time inflation makes GDP (as well as retail sales) look good.

Another factor that creates a bubble is the fact that government spending is actually included in the calculation of GDP. That’s right, every dollar of your tax money that the government wastes helps the establishment by propping up GDP numbers. This is why government spending increases will never stop – It’s too valuable for them to spend as a way to make the economy appear healthier than it is.

The REAL economy is eclipsing the fake economy

The bottom line is that Americans used to be able to ignore the warning signs because their bank accounts were not being directly affected. This is over. Now, every person in the country is dealing with a massive decline in buying power and higher prices across the board on everything – from food and fuel to housing and financial assets alike. Even the wealthy are seeing a compression to their profit and many are struggling to keep their businesses in the black.

The unfortunate truth is that the elections of 2024 will probably be the turning point at which the whole edifice comes tumbling down. Even if the public votes for change, the system is already broken and cannot be repaired without a complete overhaul.

We have consistently avoided taking our medicine and our disease has gotten worse and worse.