Government

Is current space law equipped to handle a new era of shifting power structures in space? The Conversation Weekly podcast transcript

This is a transcript of The Conversation Weekly podcast episode published on April 29 2022.

This is a transcript of The Conversation Weekly podcast episode: Ukraine invasion threatens international collaboration in space – is current space law equipped to handle a new era of shifting power structures?, published on April 27, 2022.

NOTE: Transcripts may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Gemma Ware: Hello, and welcome to The Conversation Weekly.

Dan Merino: This week, we’re diving into space politics and space law. To start, how the Russian invasion of Ukraine is affecting international collaboration in space.

David Kuan-Wei Chen: Nobody wants to see Russia, which has been such an instrumental partner in the ISS withdrawal

Gemma: We talk to two space experts to understand how space is entering a new era of international competition – and whether existing space law is ready for what comes next.

Svetla Ben-Itzak: We are actually at the very beginning of how power relations in space are being formed and developed.

Dan: I’m Dan Merino in San Francisco.

Gemma: And I’m Gemma Ware in London. You’re listening to The Conversation Weekly, the world explained by experts.

Gemma: So Dan, the war in Ukraine has been a massive political and economic story for the whole world. But how is it touching science?

Dan: It’s touching science in a bunch of ways. There’s a huge technology angle, a big environmental angle — but as someone who covers space a lot, there’s also a pretty interesting space angle to this whole thing.

Gemma: In what way?

Dan: Well, for the most part, space has traditionally been a place of collaboration in science, and this insulation from tensions and conflict on the ground is under threat right now.

Gemma: What do you mean?

Dan: Well, the first thing that happened is that Russia cancelled its Soyuz rocket launches from a European spaceport in French Guiana and this meant a lot of missions needed to figure out how to get their stuff up into orbit.

Newsclip: The Russians also cut off sales and support for Russian rocket engines used in US spacecraft.

Dan: Following that, the European space agency suspended its work with Russia on the ExoMars project to get a new rover on mars.

Newsclip: In a statement the European space agency has said and I quote “while recognising the impact of scientific exploration of space, the ESA – that is the European Space Agency – is fully aligned with the sanctions that have been imposed in Russia by its member states.”

Dan: Europe cancelled cooperation with Russia on a bunch of moon missions and of course there was all this hullabaloo about the International space station.

News clip: This morning the international space station in political cross-hairs as Russia retaliates against American sanctions.

Gemma: I heard about this – I saw a spoof video that the Russian Space Agency put together reporting to show what would happen if the Russians detached their module from the international space station.

Dan: Yes, there were videos, there were tweets from the head of Roscosmos – this guy Dmitry Rogozin. He’s a bit of a Twitter hot head but he threatened to let the ISS crash down to earth. That threat is a bit empty and NASA kinda confirmed that really quickly but Russia did threaten to pull out of the ISS completely and said that the restoration of normal relations is possible only with the complete unconditional lifting of illegal sanctions. So that’s kind of a big shot across the bow of international collaboration in space.

Gemma: So, what would happen if Russia did actually pull out of the international space station?

Dan: Well, it’s pretty complicated and it definitely wouldn’t happen overnight. And to understand it, you really need to understand both the technical operations of the ISS and also the legal framework.

David: My name is David Kuan-Wei Chen

Dan: David is the executive director of the McGill Center for Research in Air and Space Law in Canada and he’s really an expert in all things space law. I asked him to explain how the ISS really operates on a day-to-day basis.

David: Construction started in 1998 when the Russians sent the first elements up into space and then from there on, different states added their own elements. Right? So, this is part of the reason behind the controversy if Russia were to pull out completely from the space station, because the Russian element is quite essential to what they call station keeping. Right? So the Russian element has the propulsion system that maintains the space station so that it doesn’t come crashing down to earth, because you know, the earth’s gravity would naturally just pull every single object down towards earth.

And it’s also Russia, which is obligated to provide a permanent escape capsule which is docked to the ISS in case, whatever emergency that the astronauts on board need to escape and evacuate. And there are other elements that are contributed by the other partners, such as the Europeans have a science module. The Japanese also have a science and research module. Canada contributed the Canada arm, which is very instrumental in the construction and the maintenance of the space station itself.

Dan: So what laws actually govern the International Space Station in all these different modules from different countries?

David: There’s one overarching agreement between the governments of the US, Russia, Canada, Japan and 11 of the participant states of the European space agency. So this intergovernmental agreement, or the IGA, is a legally binding international treaty which lays down the basic rules on the joint development and use of the ISS. The agreement also lays down that, each module, each element of the partner, what they would contribute to the collaborative project.

Dan: You mentioned there’s a Russian module, there’s the Canada Arm, there’s the Japanese science branch. Is this like a little piece of sovereign soil up in space or what’s the actual rules here? Are we talking flags and border checkpoints or anything like that?

David: Yeah so in a sense, yes. So, according to basic space law and this is reflected in the intergovernmental agreement of the ISS, every module belongs to and is operated by that state, right? So the US module obviously is operated and maintained by the US, through its space agency, NASA, and ditto with the Russian module operated and maintained through its space agency, Roscosmos. And the law is, for instance, if there were an invention created aboard the US module, then intellectual property law of the US would apply to that creation and then there are also laws dealing with customs and immigration and so on and so on.

Dan: Oh, interesting. So like there is in fact some “customs”, on the space station. Like you don’t have to check in or anything but like if something passes through one branch to the other technically there’s the shift in laws.

David: Technically, there is a shift in law and the interesting fact is, because of the unique nature of the space station, the IGA actually has a provision dealing with criminal jurisdiction, right? If say, a crime were committed on board, what kind of laws would govern? What is unique to the ISS is that, the states have agreed they would have criminal jurisdiction over their own nationals. So, for example, if a US national were to commit a crime on board the space station then US law would apply to this US national.

Gemma: Dan, has this ever actually happened, has there ever been a crime on board the space station?

Dan: Well, somebody was accused of a crime.

Newsclip: NASA’s reportedly investigating what may be the first crime committed in space.

Dan: A couple years ago, a US astronaut, Anne McLain, was accused of using a NASA computer to access the bank account of her wife who she was divorcing at the time.

News clip: McLain’s wife reportedly filed a complaint accusing her of identity theft.

Gemma: So was it the first space crime?

Dan: Well, some people investigated and the case was actually later dropped and McLain was cleared of any wrongdoing. In a funny twist, it’s now actually McLain’s former wife who’s facing trial this year and is accused of lying to federal authorities.

Gemma: OK, so it sounds complicated! But we’ve digressed a little bit here… so back to the International Space Station. We’ve had these threats from the head of the Russian Space station, Roscosmos to withdraw from the ISS, but what has actually happened? Like, how is everything going for the astronauts up there orbiting earth.

Dan: Things seem to be going alright up in space. Russian cosmonauts just the other day did a space walk and connected a control panel to a European owned robotic arm. End of March, a NASA astronaut named Mark Vande Hei returned to earth on a Russian Soyuz space capsule with his Russian colleagues.

News clip: Touchdown! Mark Vande Hei and Pyotr Dubrov back home one year after leaving the planet.

Dan: Rogozin had actually said his return could be under threat, but you know the guy’s kinda full of hot air.

News clip: Even as tensions rise here between America and Russia, over the war in Ukraine, the crew shared a hug.

David: It just shows despite these tensions on earth, cooperation continues and the heads of NASA and the Canadian space agency have all written to their Russian counterpart to say, you know, cooperation in the ISS is independent of any geopolitical issue, and the US government and Canadian government continue to support the ISS and to ensure its success. And I think astronaut Vande Hei said it best when you said “I’ve heard about these tweets and threats, I kinda laughed it off and I moved on.”

Dan: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

David: And you know, these threats have been made before these sanctions. Actually, the Roscosmos chief Rogozin – they were actually in place at the time, the 2014 invasion of Crimea – when he was the deputy prime minister, there were sanctions imposed on him personally. And at the time, also we saw these threats that were being issued to cease the co-operation on the ISS but NASA came out and assured the world that cooperation would continue as usual and nothing has changed. And hopefully this is going to be the same as well.

Dan: So, you talked about the intergovernmental agreement that kind of governs the laws regarding ISS, from Crimea, from the invasion of Ukraine, do you feel like the laws in place are doing their job aboard the ISS? Are they strong? Are they robust? Are they involved in keeping the stability?

David: Yeah, I think so, I think so. I mean nobody wants to see Russia, which has been such an instrumental partner in the ISS, withdraw from the ISS, right? And you know, the IGA, like with any agreement, it’s not as easy as you think they “Oh, We’re gonna stop cooperation, we’re gonna withdraw from this”, because there is actually built in provision, which says, if you do want to withdraw, there is a one year period. And I think they negotiated it into this because they wanted to make sure that it’s not just a sudden withdrawal, whereby all the other partners are left in the lurch.

So, this one year withdrawal period allows them to kind of negotiate, discuss what would happen, you know, who will take over and so on and so on. And there are also provisions in the IGA, which deals with what happens when there’s this dispute. So clearly, right now, there is a dispute, and there are mechanisms in place to initiate consultation and negotiation to hopefully resolve any issues.

Like all international agreements, these provisions are in place to prevent the unnecessary escalation of political disputes or tensions which threaten to completely derail 20-30 years of unprecedented cooperation in space, right? This again, despite these tensions, the ISS has continued to operate and space has really has always been an arena that’s kind of, isolated from tensions on earth and we hope this continues to be the case with the ISS.

Gemma: You know, David mentioned there was this long history of scientific collaboration in space … but that wasn’t always the case, right? I mean, I, in my head, I think of the space race between the US and the Soviets during the cold war and lots of competition – it was a tense period.

Dan: Yes, it certainly was a time of tension. There was a lot of competition to become the space dominant player but there was a surprising amount of collaboration too. Notably, there was the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz test, where an American Apollo spacecraft, carrying three US astronauts, docked with a Russian Soyuz spacecraft carrying a couple Russian cosmonauts. They not only docked in orbit – first time that ever happened – but they shook hands.

Gemma: Friendly!

Dan: Friendly… during the middle of the cold war when the United States and Russia all thought they were gonna nuke each other. There’s also been a bunch of kinda more international efforts. There was the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the 1979 Moon Agreement and we’re gonna hear a lot more about those later.

Gemma: So this was a moment of real tension on earth and yet in space things were you know not so hostile?

Dan: It wasn’t and it was actually really both in the US and the Soviet Union’s strategic interests to restrain themselves in space in a sense. Space is such a global good, and at that time there was so much room for technological growth and advancement. It was more of a rising tide lifts all boats and not so much a zero sum game. At least back then.

Gemma: So the US and the Soviets started collaborating in space – what happened from there?

Dan: Well, slowly as other countries gained their own space abilities they got in the game too. France became the third country to put a satellite in space in 1965. In the 70s, a group of European nations formed the European Space Agency. This is the ESA. And now they’ve got 22 member states. But the European Space Agency was the first side of things to come. As more and more nations gained access to space and especially in the last couple decades alliances, treaties, collaboration, have gotten a lot more complicated. And to understand what’s been happening to get us where we are today and what might happen next – I called up someone who studies power itself and how it’s divided in space.

Svetla: My name is Svetla Ben-Itzak.

Dan: Svetla is an assistant professor of space and international relations at Air University in the US, where she works with and trains senior members of the US space force.

Svetla: And I teach courses on space security, international security, and the like. However, I would like to say that the views that I express here are my own.

Dan: Today, more than 70 countries have an official space agency of some sort. An additional roughly 26 or so have at least one satellite in orbit. But as Svetla explained, some countries are still clear leaders.

Svetla: We can say the top five leading space faring countries are the US, China, Russia, Japan, and India. And of course the European Space Agency is up there among the top six.

Dan: So with all these newcomers entering the space game, how has the nature of international collaboration changed?

Svetla: So, in the past, we had individual countries leading in space, however, nowadays, more often than not, in space, they’re not acting alone. So the trend has been that countries that partner on the ground also come together in space to accomplish specific missions in space. So I call such formation space blocs. So it makes sense for countries to come together to pool their resources, manpower, expertise, and know-how, to accomplish more. Right. So those space blocs have most of them formed over the last five to 10 years, right?

Dan: So, this is super recent?

Svetla: Very recent. Especially the ones that actually have specific missions to accomplish in space.

Dan: Who are these space blocs? What are the kinds of big players and who’s in them?

Svetla: We have the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization also known as APSCo. This one was formed back in 2005. We have the Latin American and Caribbean Space Agency kind of bloc. That was from just last year in 2021 and currently has seven countries led by Argentina. We have the Arab Space Coordination Group, formed in 2019 by the United Arab Emirates. Currently it has about ten Arab countries. And of course you have the African Space Agency.

Dan: The race to the moon and in particular a moon base, this is a pretty good example where these blocs are kind of in play. So can you describe what’s going on there?

Svetla: Yes. On one hand we have the Artemis Accords, an international agreement signed in October 2020, initiated and led by the United States.

News clip: We’re going to the moon sustainably – in other words this time when we go to the Moon we’re gonna stay at the Moon for long periods of time.

Svetla: The main objective is to put a man and a woman back on the Moon by 2025 with the ultimate goal of expanding space exploration to Mars and beyond, right. We have 18 countries signatories to the accords. The last two to join were Bahrain and Singapore and also the Isle of Man, actually.

News clip: Ushering in a new era of space cooperation between Russia and China – the two countries have signed a memorandum that sets in motion plans to join the space station, either on the Moon’s surface or in its orbit.

Svetla: On the other hand, we have another space bloc formed by an agreement between Russia and China, that dates back to 2019 when both countries actually affirmed their intent to work together and established an international lunar space station by 2026, again, on the south pole of the Moon.

Dan: Why aren’t they working together? Right. Like what’s going on here?

Svetla: Well, my argument is that this separation reflects actually strategic interests and uncertainties about the security intentions on the ground that have been kind of transposed to space and one supporting evidence to that is that although the Artemus Accords, are open to any nation to join in – anybody can join in – Russia and China have been reluctant, they have not become signatories. And some argue not only Russia and China, but also some scholars argue that those accords are an effort to expand US-centered and US-defined order to outer space. Right?

Read more: Artemis Accords: why many countries are refusing to sign Moon exploration agreement

So through space blocs actually countries consolidate their sphere of influence. Not only on the ground, but also in space. Right, so on our side, we’re also are not running into kind of joining the Sino-Russian space bloc. I mean, I argue that, for example, the Asia Pacific Space Cooperation Organization, the APSCo led by China that was established back in 2005 and currently has eight members namely Bangladesh, Pakistan, Mongolia, Peru, Thailand and Turkey. So China is using this bloc to expand its influence in the area via its space, satellite services that it provides to the members.

So my argument here is that countries actually use those space blocs to consolidate and expand their sphere of influence both on the ground and in space. The question is how many such space blocs will develop? Whether there will be some connection between the blocs based on scientific interests? And whether those blocs will actually consolidate even further and exclude anybody who would be interested in joining? So we are actually are at the very beginning of how power relations in space are being formed and developed.

Dan: And that certainly makes things interesting. So, how do the commercial actors play into this whole world?

Svetla: So let me just kind of like set the stage a little bit because over the last 15 years, thanks to federal deregulation specifically in the United States, commercial activity in space, more than tripled. In 2020, commercial activity accounted for about 80% of the total global space economy. And some scholars see that this is the future of international cooperation in space, through commercial entities and shared commercial interests, right? Because commercial companies will actually decrease this inherent uncertainty as to what we think the others will do. Right? I argue personally that although important, I think commercial entities will remain subject to state actors, because states dictate what goes in space.

They dictate the rules in space. And one example for that is the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which provides the basic legal framework of international space law. So the Outer Space Treaty gives states full responsibility, liability and ownership of any commercial entity that operates in space.

Dan: Can you explain what you mean by that? As in, SpaceX launches a rocket – it’s technically the US launching a rocket, right?

Svetla: Yes, absolutely. Actually, nothing flies into outer space without registering with a state first and being allowed by the state to fly. And of course, to return, because states are responsible and liable for any object or person that happens in space. And they also own it, in terms of the rules of states that apply on that specific spacecraft as well as people, right.

Dan: I want to move on to the invasion of Ukraine and would you say that this recent event is kind of that first test of the new kind of order of space, the first big shock to the system, if you will? And if so, how’s it playing out?

Svetla: It is not the first and it won’t be the last. It happened many times in the past. The war in Crimea was very similar to what’s happening right now. But what is happening now really evidences what I’ve been arguing, namely the primacy of states over commercial actors in space affairs. Right?

So for example, in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, western countries imposed a number of sanctions against Russia. And as a result of those sanctions, many commercial companies actually stopped collaborating with Russia’s space agency Roscosmos. So, the British satellite company, OneWeb, suspended all launches from Russia’s Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Scientific collaboration with Russia in space also ceased. For example, Germany discontinued their scientific collaboration with Russia on the International Space Station.

Dan: Do you think the invasion of Ukraine and all these actions that are being imposed sanctions, lack of scientific collaboration. Is this further ossifying space blocs or what is it kind of doing to the trend line?

Svetla: The unfortunate effect in this particular case is that tensions on the ground for now seem to have kind of rigidified the system even further in space, right? Have had negative consequences on scientific collaboration in space and commercial collaboration. Now in the past, what happened in space actually weathered storms on the ground, and collaborations survived, and even thrived despite tensions on the ground. So we’ll just have to wait and see if those will have some long-term effects on the pace blocs in general or on specific scientific missions.

Dan: Are there risks to this? Are there any parallels you can draw to some historical places on land, perhaps?

Svetla: Yes, absolutely. So, if history is to serve us as any kind of warning precedent or lesson? I would say we should be reminded of what happened just before world war one. The lesson there that the more rigid alliances become, an inflexible alliances become, such as the growing rigidity of the two alliances, the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of 20th century. The growing rigidity of the two alliances is often cited as a triggering cause of world war one at the systemic level, right? And also cited as the war was inevitable, right? So I think we can draw a lesson that as long as existing space blocs remain flexible, open to all, willing to accommodate very often diverging interests – cooperation will continue and, we may avoid an open conflict in space.

Dan: So, given all of these trends, Svetla, are you optimistic about the future of space or are these space blocs that are emerging potentially a bad thing?

Svetla: I want to be optimistic about the future, but I also can see that things may develop into a different kind of, not so optimistic pathway. So, if we manage to keep the uncertainty about the intentions of others at bay and focus on the scientific missions at hand – actually pooling our resources together in those space blocs will help us accomplish this faster and will help us go further for the benefit of all. The bad news here is that, if security interests that are usually based on the fact that we are uncertain as to what the other side is trying to accomplish, override current space mission objectives – this may lead to further rigidity of the existing space blocs, which will limit our options and it will spiral us down into an undesired path of confrontation and conflict.

Gemma: So, Dan, a space war sounds like science fiction but also very scary … how did you leave your conversation with Svetla? Did you feel like it was going to happen any time soon?

Dan: Gosh, I certainly hope not. But it’s hard to predict. So I’m not going to go on the record books here. But I do think it’s very interesting how the structures of power and the structures of relations in space are shifting towards a place that might in fact be more conducive to conflict and that’s scary.

Gemma: And is there anything preventing us from having a war in space?

Dan: I guess the one thing kind of preventing it is sort of space law but that’s a really big grey area.

Gemma: We heard a little bit about the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. Is that not going to help?

Dan: Well it might and David Kuan-Wei Chen actually talked about this a little bit.

David: That treaty together with a series of other UN treaties were adopted in the 1960s and 70s, at the height of the cold war and it’s quite miraculous that the Soviet Union and United States came together at the UN to lay down the basic principles, what you can and cannot do. They agreed that you cannot own space or own celestial bodies such as the moon or asteroids and so on and so on. Even then they agreed on the fundamental principle that you cannot use nuclear weapons or weapons of mass destruction in space. And there’s also, a very general consensus on the fact that the exploration and use of outer space should be for so-called peaceful purposes. So, even at the time they recognised that outer space is not a lawless, wild west domain, where anyone can do anything.

Dan: Things have changed a lot. Do you think that space law is well-equipped to deal with today’s problems? Especially with all the ways different countries and companies are aligning themselves and using space?

David: Yeah, so I think one major problem is the possibility and the fear of an extension of conflict into outer space. So yes, when they were drafting the space law treaties at the UN, they made sure that there’ll be no military manoeuvres, no testing of any kind of weapons on the Moon. But then there’s a legal vacuum because that doesn’t address the testing of weapons in outer space. And so we saw unfortunately it was Russia that tested a weapon in November 2021.

News clip: The US has condemned Russia for conducting a dangerous and irresponsible missile test that it says endangered the crew aboard the International Space Station.

David: So they tested what they call an anti-satellite weapon, basically using a missile to destroy its own satellite. And that created a whole bunch of debris that really threatened, potentially, the space objects of other states.

News clip: Station Houston on space to ground two, for an early wake up. Astronauts aboard the international space station were awakened overnight by NASA flight controllers in Houston.

David: Astronauts on board the International Space Station had to temporarily evacuate into the capsule, you know, in case they had to flee oncoming space debris.

Dan: When there’s clear laws in place if an actor does something that breaks international law or violates something, response is justified, right? My worry is that without clear guidance, there’s a little more leeway, right? Like Russia can rattle, a sabre in space, and what is the response? Because it isn’t breaking any laws. So is this kind of like grey area a problem that people are thinking about?

David: Yeah. it is. And so my background is in law. So, you know, I see the world in terms of law of rights and obligations and, what, what we’re seeing right now is increasing recognition of threats to space activities and space objects. Which is a great thing, but there’s also a shift from how to address these threats, right?

So in the 60s and 70s, we adopted a series of UN space law treaties, which are legally binding. And there are consequences if you were to violate such legal principles and norms, then now the dialogue is increasingly moving towards the adoption of so-called guidelines for the long-term sustainable use of outer space and more recently, states are discussing about norms and rules and principles of responsible behaviour, which are based on, you know, shared values and expectations of what is appropriate behaviour. But what happens when someone breaks a norm or does not behave responsibly?

Dan: Sure, sure, Sure.

David: I mentioned earlier the Russian ASAT test in November. Many states came out and condemned the action as irresponsible behaviour. That’s it.

Dan: But then what? You can’t do anything else, right? Yeah.

David: Exactly! I’m not singling out Russia.

Dan: Sure, sure, sure.

David: You know, the United States, China, India they have all conducted ASAT tests in space. But there’s a big difference between calling someone an irresponsible actor and calling someone a law breaker. Because when someone is a law breaker, there are potential obligations, potentially – if you were to cause damage, then you may have to compensate. And there are legal consequences. There are also potential political fallout of being cast as an outlaw. And so, this is something that we are quite concerned with.

Dan: Do you think that law can play a role in maintaining cooperation and flexibility as space changes and as technologies improve?

David: Yeah, I think so. I mean, again, you know, really the testament and the legacy of the Outer Space Treaty and the series of UN space law treaties is that they remain relevant til this day.

Dan: And you do think that? Like I like cause that that’s there so old what it’s crazy that we are actually still relevant.

David: Yeah, but you know, you can say the same about the laws of war, right? The laws of war were developed on Earth, originally in the 1800s, ironically in the Crimea, because the founder of the International Committee of the Red Cross saw such devastation and tragedy happening to the civilian population that, you know, you said there must be basic principles of what we cannot do in an armed conflict situation. That’s over a hundred years ago, but those still remain relevant to this day; remain relevant to the conflict situation in Ukraine, in Afghanistan, in Yemen and so on.

So, even though laws may be old, that doesn’t mean they’re necessarily outdated. And I think the strength of the space law treaties is that perhaps with foresight, they were drafted in such a way that you can interpret them and apply them to new contexts and new situations.

Dan: David and his colleagues at McGill are currently putting together a new manual – the goal to actually clarify a lot of the grey areas in space law and turn some of the unwritten rules of space into actual written rules.

Gemma: And is some of this about who owns space as well? Because Svetla talked about these two kinds of slightly competing missions going to the south pole of the Moon – what if they find water there, or minerals or something they want to exploit?

Dan: It’s less a question of if they will find it because we know it’s there. It’s more of a question who’s got the rights to do what with it? And that’s exactly why these two missions are going there – to see what they can do to exploit these resources and David actually talked about this a lot too.

David: I think what would be very interesting to see, especially as countries return to the Moon, is how they interpret international law. So we have the United States, especially, rallying countries around the world to sign up to the Artemis Accords, which, which lays down the basic, political commitments. They’re not actually legal obligations, they’re political commitments of what they’re going to do on the Moon. Which includes the exploration and exploitation of space resources. Now, how does, for example, going to the Moon and extracting resources square with that international legal obligation established very clearly in 1967? And there are a number of countries, Japan being the latest one, in addition to Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates and the United States, which have passed national legislation saying, we recognise that private actors can go and exploit space resources, and have rights over such space resources.

Dan: Oh, so the rights is the important part there, right?

David: Right! Yeah. So, how does that square with the overarching concept of non-appropriation under international space law? One of the UN space law treaties is called the Moon Agreement, which was adopted in 1979, which envisions the establishment of an international regulatory body to deal with the extraction and the sharing of lunar resources. To date, there are only 18 states that are parties to the Moon Agreement – none of which are major space-faring countries.

Dan: So we’ve talked about the Moon and missions to establish bases there, but what about further out into space, like Mars for example or maybe moons of Saturn, eventually?

David: Yeah. So, the Moon Agreement, even though the name is Moon Agreement, it actually applies to celestial bodies in the solar system. Technically the Moon Agreement would apply to activities in the exploration and use of resources on Mars. And that’s, that’s something that I think, you know, Elon Musk has been saying, you know, it may happen in the 2030s and so on. Again, not many countries have signed up to the Moon Agreement so therefore those obligations under Moon Agreement do not apply to them. And so I think the big question with the next steps of space exploration and habitation is how do you make sure that these laws that were drafted on Earth apply and are enforceable in extra terrestrial contexts?

Dan: So not only do we have the grey area kind of hole, we’ve got the enforcement hole, which certainly, you know, a law doesn’t matter if it’s not enforced.

David: Yeah. And, you know, there was, again, I’m not trying to single out, Elon Musk, but he floated this idea, people can sign up for missions to Mars and basically work to pay back there…

Dan: Oh gosh.

David: And that sounds like something, unfortunately sounds like indentured servitude.

Dan: Yeah, we’ve got plenty of history and plenty of sci-fi shows to warn us against this.

David: That’s right. So, I think, it’s great that we are seeing more private and commercial investment in space which means, you know, governments do not have to dedicate so much of their financial resources to space exploration because you know, these billionaires are willing to spend their money and fortunes, hopefully for the benefit of humankind. But you know, it may also then raise the concerns of whether again, looking back at history, we’ve seen the history of privateers; people going to new territories and new worlds and saying, well, we’re going to exploit. We’re going to colonise. What does that mean? Again, it comes down to what impact will that have on the international binding laws that the states have agreed on for so many decades.

Gemma: When you think about it, it’s actually the richest countries in the world who have the resources to go to space. So it’s the richest countries that are gonna benefit from it. So really finding a way to make sure those laws are enforced is incredibly important to equity to space resources in the future.

Dan: Absolutely and again it’s all about resources. To kinda close the loop on this episode. I really was shocked when all this stuff started bubbling up about tensions between Russia and the United States in space. I had this kind of naive bubble that space was some happy-go-lucky place of collaboration and science and that it was in some way insulated from the realpolitik of earthly tensions. the invasion of Ukraine and all the fallout from that has really kind of shattered that bubble for me and as Svetla explained this has not been a surprise for those who have been paying attention for it and that’s because of the technology changes and because there so many people going into space, and because there’s this competition and so, space needs laws.

Gemma: It definitely does.

Gemma: If you want to learn more about how the Russian invasion of Ukraine has affected scientific collaboration, including in space, we’ve been publishing a few articles about that on The Conversation including from Svetla and David.

Dan: We’ll put some links to their stories in the show notes as well as a few others.

Gemma: Before we go, Australians are going to the polls on the 21 May in a federal election. And a new podcast from The Conversation is digging into some of the political issues ahead of the vote.

Jon Faine: Hello I’m Jon Faine, former ABC Melbourne presenter and now a vice chancellor’s fellow at the University of Melbourne. If you’ve been enjoying The Conversation Weekly I hope you’ll love our new podcast Below the Line from The Conversation, Australia and La Trobe University covering the Australian federal election campaign 2022.

Amid the global headwinds of COVID-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and local crisis here, the devastating floods, the government of prime minister Scott Morrison is behind in the polls. Can he turn things around or will the Labor Party take back power in our election in May. I’ll be joined by political scientists Anika Gauja and Simon Jackman from the University of Sydney and La Trobe University’s Andrea Carson. Around twice a week we’ll try to do it to unpack the party lines and policies that matter. To listen and subscribe, search for Below the Line on The Conversation or your favourite podcast app.

Gemma: That’s it for this week. Thanks to all the academics who’ve spoken to us for this episode. And thanks to the conversation’s Nehal el-Hadi and Stephen Khan and to Alice Mason for our social media permission.

Dan: You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio, on Instagram at theconversationdotcom or via email. Don’t forget to sign up for our free daily email as well and hey – tell a friend if you liked this episode.

Gemma: The Conversation Weekly is co-produced by Mend Mariwany and me Gemma Ware with sound design by Eloise Stevens. Our theme music is by Neeta Sarl.

Dan: I’m Dan Merino, thank you for listening!

Kuan-Wei (David) Chen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Svetla Ben-Itzhak does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

us government covid-19 testing singapore india japan canada european europe france germany russia ukraine chinaInternational

Four Years Ago This Week, Freedom Was Torched

Four Years Ago This Week, Freedom Was Torched

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Brownstone Institute,

"Beware the Ides of March,” Shakespeare…

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Brownstone Institute,

"Beware the Ides of March,” Shakespeare quotes the soothsayer’s warning Julius Caesar about what turned out to be an impending assassination on March 15. The death of American liberty happened around the same time four years ago, when the orders went out from all levels of government to close all indoor and outdoor venues where people gather.

It was not quite a law and it was never voted on by anyone. Seemingly out of nowhere, people who the public had largely ignored, the public health bureaucrats, all united to tell the executives in charge – mayors, governors, and the president – that the only way to deal with a respiratory virus was to scrap freedom and the Bill of Rights.

And they did, not only in the US but all over the world.

The forced closures in the US began on March 6 when the mayor of Austin, Texas, announced the shutdown of the technology and arts festival South by Southwest. Hundreds of thousands of contracts, of attendees and vendors, were instantly scrapped. The mayor said he was acting on the advice of his health experts and they in turn pointed to the CDC, which in turn pointed to the World Health Organization, which in turn pointed to member states and so on.

There was no record of Covid in Austin, Texas, that day but they were sure they were doing their part to stop the spread. It was the first deployment of the “Zero Covid” strategy that became, for a time, official US policy, just as in China.

It was never clear precisely who to blame or who would take responsibility, legal or otherwise.

This Friday evening press conference in Austin was just the beginning. By the next Thursday evening, the lockdown mania reached a full crescendo. Donald Trump went on nationwide television to announce that everything was under control but that he was stopping all travel in and out of US borders, from Europe, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. American citizens would need to return by Monday or be stuck.

Americans abroad panicked while spending on tickets home and crowded into international airports with waits up to 8 hours standing shoulder to shoulder. It was the first clear sign: there would be no consistency in the deployment of these edicts.

There is no historical record of any American president ever issuing global travel restrictions like this without a declaration of war. Until then, and since the age of travel began, every American had taken it for granted that he could buy a ticket and board a plane. That was no longer possible. Very quickly it became even difficult to travel state to state, as most states eventually implemented a two-week quarantine rule.

The next day, Friday March 13, Broadway closed and New York City began to empty out as any residents who could went to summer homes or out of state.

On that day, the Trump administration declared the national emergency by invoking the Stafford Act which triggers new powers and resources to the Federal Emergency Management Administration.

In addition, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a classified document, only to be released to the public months later. The document initiated the lockdowns. It still does not exist on any government website.

The White House Coronavirus Response Task Force, led by the Vice President, will coordinate a whole-of-government approach, including governors, state and local officials, and members of Congress, to develop the best options for the safety, well-being, and health of the American people. HHS is the LFA [Lead Federal Agency] for coordinating the federal response to COVID-19.

Closures were guaranteed:

Recommend significantly limiting public gatherings and cancellation of almost all sporting events, performances, and public and private meetings that cannot be convened by phone. Consider school closures. Issue widespread ‘stay at home’ directives for public and private organizations, with nearly 100% telework for some, although critical public services and infrastructure may need to retain skeleton crews. Law enforcement could shift to focus more on crime prevention, as routine monitoring of storefronts could be important.

In this vision of turnkey totalitarian control of society, the vaccine was pre-approved: “Partner with pharmaceutical industry to produce anti-virals and vaccine.”

The National Security Council was put in charge of policy making. The CDC was just the marketing operation. That’s why it felt like martial law. Without using those words, that’s what was being declared. It even urged information management, with censorship strongly implied.

The timing here is fascinating. This document came out on a Friday. But according to every autobiographical account – from Mike Pence and Scott Gottlieb to Deborah Birx and Jared Kushner – the gathered team did not meet with Trump himself until the weekend of the 14th and 15th, Saturday and Sunday.

According to their account, this was his first real encounter with the urge that he lock down the whole country. He reluctantly agreed to 15 days to flatten the curve. He announced this on Monday the 16th with the famous line: “All public and private venues where people gather should be closed.”

This makes no sense. The decision had already been made and all enabling documents were already in circulation.

There are only two possibilities.

One: the Department of Homeland Security issued this March 13 HHS document without Trump’s knowledge or authority. That seems unlikely.

Two: Kushner, Birx, Pence, and Gottlieb are lying. They decided on a story and they are sticking to it.

Trump himself has never explained the timeline or precisely when he decided to greenlight the lockdowns. To this day, he avoids the issue beyond his constant claim that he doesn’t get enough credit for his handling of the pandemic.

With Nixon, the famous question was always what did he know and when did he know it? When it comes to Trump and insofar as concerns Covid lockdowns – unlike the fake allegations of collusion with Russia – we have no investigations. To this day, no one in the corporate media seems even slightly interested in why, how, or when human rights got abolished by bureaucratic edict.

As part of the lockdowns, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which was and is part of the Department of Homeland Security, as set up in 2018, broke the entire American labor force into essential and nonessential.

They also set up and enforced censorship protocols, which is why it seemed like so few objected. In addition, CISA was tasked with overseeing mail-in ballots.

Only 8 days into the 15, Trump announced that he wanted to open the country by Easter, which was on April 12. His announcement on March 24 was treated as outrageous and irresponsible by the national press but keep in mind: Easter would already take us beyond the initial two-week lockdown. What seemed to be an opening was an extension of closing.

This announcement by Trump encouraged Birx and Fauci to ask for an additional 30 days of lockdown, which Trump granted. Even on April 23, Trump told Georgia and Florida, which had made noises about reopening, that “It’s too soon.” He publicly fought with the governor of Georgia, who was first to open his state.

Before the 15 days was over, Congress passed and the president signed the 880-page CARES Act, which authorized the distribution of $2 trillion to states, businesses, and individuals, thus guaranteeing that lockdowns would continue for the duration.

There was never a stated exit plan beyond Birx’s public statements that she wanted zero cases of Covid in the country. That was never going to happen. It is very likely that the virus had already been circulating in the US and Canada from October 2019. A famous seroprevalence study by Jay Bhattacharya came out in May 2020 discerning that infections and immunity were already widespread in the California county they examined.

What that implied was two crucial points: there was zero hope for the Zero Covid mission and this pandemic would end as they all did, through endemicity via exposure, not from a vaccine as such. That was certainly not the message that was being broadcast from Washington. The growing sense at the time was that we all had to sit tight and just wait for the inoculation on which pharmaceutical companies were working.

By summer 2020, you recall what happened. A restless generation of kids fed up with this stay-at-home nonsense seized on the opportunity to protest racial injustice in the killing of George Floyd. Public health officials approved of these gatherings – unlike protests against lockdowns – on grounds that racism was a virus even more serious than Covid. Some of these protests got out of hand and became violent and destructive.

Meanwhile, substance abuse rage – the liquor and weed stores never closed – and immune systems were being degraded by lack of normal exposure, exactly as the Bakersfield doctors had predicted. Millions of small businesses had closed. The learning losses from school closures were mounting, as it turned out that Zoom school was near worthless.

It was about this time that Trump seemed to figure out – thanks to the wise council of Dr. Scott Atlas – that he had been played and started urging states to reopen. But it was strange: he seemed to be less in the position of being a president in charge and more of a public pundit, Tweeting out his wishes until his account was banned. He was unable to put the worms back in the can that he had approved opening.

By that time, and by all accounts, Trump was convinced that the whole effort was a mistake, that he had been trolled into wrecking the country he promised to make great. It was too late. Mail-in ballots had been widely approved, the country was in shambles, the media and public health bureaucrats were ruling the airwaves, and his final months of the campaign failed even to come to grips with the reality on the ground.

At the time, many people had predicted that once Biden took office and the vaccine was released, Covid would be declared to have been beaten. But that didn’t happen and mainly for one reason: resistance to the vaccine was more intense than anyone had predicted. The Biden administration attempted to impose mandates on the entire US workforce. Thanks to a Supreme Court ruling, that effort was thwarted but not before HR departments around the country had already implemented them.

As the months rolled on – and four major cities closed all public accommodations to the unvaccinated, who were being demonized for prolonging the pandemic – it became clear that the vaccine could not and would not stop infection or transmission, which means that this shot could not be classified as a public health benefit. Even as a private benefit, the evidence was mixed. Any protection it provided was short-lived and reports of vaccine injury began to mount. Even now, we cannot gain full clarity on the scale of the problem because essential data and documentation remains classified.

After four years, we find ourselves in a strange position. We still do not know precisely what unfolded in mid-March 2020: who made what decisions, when, and why. There has been no serious attempt at any high level to provide a clear accounting much less assign blame.

Not even Tucker Carlson, who reportedly played a crucial role in getting Trump to panic over the virus, will tell us the source of his own information or what his source told him. There have been a series of valuable hearings in the House and Senate but they have received little to no press attention, and none have focus on the lockdown orders themselves.

The prevailing attitude in public life is just to forget the whole thing. And yet we live now in a country very different from the one we inhabited five years ago. Our media is captured. Social media is widely censored in violation of the First Amendment, a problem being taken up by the Supreme Court this month with no certainty of the outcome. The administrative state that seized control has not given up power. Crime has been normalized. Art and music institutions are on the rocks. Public trust in all official institutions is at rock bottom. We don’t even know if we can trust the elections anymore.

In the early days of lockdown, Henry Kissinger warned that if the mitigation plan does not go well, the world will find itself set “on fire.” He died in 2023. Meanwhile, the world is indeed on fire. The essential struggle in every country on earth today concerns the battle between the authority and power of permanent administration apparatus of the state – the very one that took total control in lockdowns – and the enlightenment ideal of a government that is responsible to the will of the people and the moral demand for freedom and rights.

How this struggle turns out is the essential story of our times.

CODA: I’m embedding a copy of PanCAP Adapted, as annotated by Debbie Lerman. You might need to download the whole thing to see the annotations. If you can help with research, please do.

* * *

Jeffrey Tucker is the author of the excellent new book 'Life After Lock-Down'

Government

CDC Warns Thousands Of Children Sent To ER After Taking Common Sleep Aid

CDC Warns Thousands Of Children Sent To ER After Taking Common Sleep Aid

Authored by Jack Phillips via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

A…

Authored by Jack Phillips via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

A U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) paper released Thursday found that thousands of young children have been taken to the emergency room over the past several years after taking the very common sleep-aid supplement melatonin.

The agency said that melatonin, which can come in gummies that are meant for adults, was implicated in about 7 percent of all emergency room visits for young children and infants “for unsupervised medication ingestions,” adding that many incidents were linked to the ingestion of gummy formulations that were flavored. Those incidents occurred between the years 2019 and 2022.

Melatonin is a hormone produced by the human body to regulate its sleep cycle. Supplements, which are sold in a number of different formulas, are generally taken before falling asleep and are popular among people suffering from insomnia, jet lag, chronic pain, or other problems.

The supplement isn’t regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and does not require child-resistant packaging. However, a number of supplement companies include caps or lids that are difficult for children to open.

The CDC report said that a significant number of melatonin-ingestion cases among young children were due to the children opening bottles that had not been properly closed or were within their reach. Thursday’s report, the agency said, “highlights the importance of educating parents and other caregivers about keeping all medications and supplements (including gummies) out of children’s reach and sight,” including melatonin.

The approximately 11,000 emergency department visits for unsupervised melatonin ingestions by infants and young children during 2019–2022 highlight the importance of educating parents and other caregivers about keeping all medications and supplements (including gummies) out of children’s reach and sight.

The CDC notes that melatonin use among Americans has increased five-fold over the past 25 years or so. That has coincided with a 530 percent increase in poison center calls for melatonin exposures to children between 2012 and 2021, it said, as well as a 420 percent increase in emergency visits for unsupervised melatonin ingestion by young children or infants between 2009 and 2020.

Some health officials advise that children under the age of 3 should avoid taking melatonin unless a doctor says otherwise. Side effects include drowsiness, headaches, agitation, dizziness, and bed wetting.

Other symptoms of too much melatonin include nausea, diarrhea, joint pain, anxiety, and irritability. The supplement can also impact blood pressure.

However, there is no established threshold for a melatonin overdose, officials have said. Most adult melatonin supplements contain a maximum of 10 milligrams of melatonin per serving, and some contain less.

Many people can tolerate even relatively large doses of melatonin without significant harm, officials say. But there is no antidote for an overdose. In cases of a child accidentally ingesting melatonin, doctors often ask a reliable adult to monitor them at home.

Dr. Cora Collette Breuner, with the Seattle Children’s Hospital at the University of Washington, told CNN that parents should speak with a doctor before giving their children the supplement.

“I also tell families, this is not something your child should take forever. Nobody knows what the long-term effects of taking this is on your child’s growth and development,” she told the outlet. “Taking away blue-light-emitting smartphones, tablets, laptops, and television at least two hours before bed will keep melatonin production humming along, as will reading or listening to bedtime stories in a softly lit room, taking a warm bath, or doing light stretches.”

In 2022, researchers found that in 2021, U.S. poison control centers received more than 52,000 calls about children consuming worrisome amounts of the dietary supplement. That’s a six-fold increase from about a decade earlier. Most such calls are about young children who accidentally got into bottles of melatonin, some of which come in the form of gummies for kids, the report said.

Dr. Karima Lelak, an emergency physician at Children’s Hospital of Michigan and the lead author of the study published in 2022 by the CDC, found that in about 83 percent of those calls, the children did not show any symptoms.

However, other children had vomiting, altered breathing, or other symptoms. Over the 10 years studied, more than 4,000 children were hospitalized, five were put on machines to help them breathe, and two children under the age of two died. Most of the hospitalized children were teenagers, and many of those ingestions were thought to be suicide attempts.

Those researchers also suggested that COVID-19 lockdowns and virtual learning forced more children to be at home all day, meaning there were more opportunities for kids to access melatonin. Also, those restrictions may have caused sleep-disrupting stress and anxiety, leading more families to consider melatonin, they suggested.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

International

Red Candle In The Wind

Red Candle In The Wind

By Benjamin PIcton of Rabobank

February non-farm payrolls superficially exceeded market expectations on Friday by…

By Benjamin PIcton of Rabobank

February non-farm payrolls superficially exceeded market expectations on Friday by printing at 275,000 against a consensus call of 200,000. We say superficially, because the downward revisions to prior months totalled 167,000 for December and January, taking the total change in employed persons well below the implied forecast, and helping the unemployment rate to pop two-ticks to 3.9%. The U6 underemployment rate also rose from 7.2% to 7.3%, while average hourly earnings growth fell to 0.2% m-o-m and average weekly hours worked languished at 34.3, equalling pre-pandemic lows.

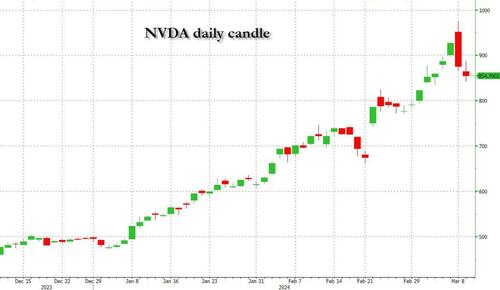

Undeterred by the devil in the detail, the algos sprang into action once exchanges opened. Market darling NVIDIA hit a new intraday high of $974 before (presumably) the humans took over and sold the stock down more than 10% to close at $875.28. If our suspicions are correct that it was the AIs buying before the humans started selling (no doubt triggering trailing stops on the way down), the irony is not lost on us.

The 1-day chart for NVIDIA now makes for interesting viewing, because the red candle posted on Friday presents quite a strong bearish engulfing signal. Volume traded on the day was almost double the 15-day simple moving average, and similar price action is observable on the 1-day charts for both Intel and AMD. Regular readers will be aware that we have expressed incredulity in the past about the durability the AI thematic melt-up, so it will be interesting to see whether Friday’s sell off is just a profit-taking blip, or a genuine trend reversal.

AI equities aside, this week ought to be important for markets because the BTFP program expires today. That means that the Fed will no longer be loaning cash to the banking system in exchange for collateral pledged at-par. The KBW Regional Banking index has so far taken this in its stride and is trading 30% above the lows established during the mini banking crisis of this time last year, but the Fed’s liquidity facility was effectively an exercise in can-kicking that makes regional banks a sector of the market worth paying attention to in the weeks ahead. Even here in Sydney, regulators are warning of external risks posed to the banking sector from scheduled refinancing of commercial real estate loans following sharp falls in valuations.

Markets are sending signals in other sectors, too. Gold closed at a new record-high of $2178/oz on Friday after trading above $2200/oz briefly. Gold has been going ballistic since the Friday before last, posting gains even on days where 2-year Treasury yields have risen. Gold bugs are buying as real yields fall from the October highs and inflation breakevens creep higher. This is particularly interesting as gold ETFs have been recording net outflows; suggesting that price gains aren’t being driven by a retail pile-in. Are gold buyers now betting on a stagflationary outcome where the Fed cuts without inflation being anchored at the 2% target? The price action around the US CPI release tomorrow ought to be illuminating.

Leaving the day-to-day movements to one side, we are also seeing further signs of structural change at the macro level. The UK budget last week included a provision for the creation of a British ISA. That is, an Individual Savings Account that provides tax breaks to savers who invest their money in the stock of British companies. This follows moves last year to encourage pension funds to head up the risk curve by allocating 5% of their capital to unlisted investments.

As a Hail Mary option for a government cruising toward an electoral drubbing it’s a curious choice, but it’s worth highlighting as cash-strapped governments increasingly see private savings pools as a funding solution for their spending priorities.

Of course, the UK is not alone in making creeping moves towards financial repression. In contrast to announcements today of increased trade liberalisation, Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmers has in the recent past flagged his interest in tapping private pension savings to fund state spending priorities, including defence, public housing and renewable energy projects. Both the UK and Australia appear intent on finding ways to open up the lungs of their economies, but government wants more say in directing private capital flows for state goals.

So, how far is the blurring of the lines between free markets and state planning likely to go? Given the immense and varied budgetary (and security) pressures that governments are facing, could we see a re-up of WWII-era Victory bonds, where private investors are encouraged to do their patriotic duty by directly financing government at negative real rates?

That would really light a fire under the gold market.

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges