International

Inside Vertex 3.0: Can Reshma Kewalramani repeat one of biotech’s biggest success stories ‘again and again and again’?

This was not how Reshma Kewalramani imagined spending her first day as Vertex CEO. The 47-year-old nephrologist should’ve been in a spacious window office on the 14th floor of the biotech’s glassy Boston Seaport headquarters, three rooms down from…

This was not how Reshma Kewalramani imagined spending her first day as Vertex CEO. The 47-year-old nephrologist should’ve been in a spacious window office on the 14th floor of the biotech’s glassy Boston Seaport headquarters, three rooms down from where she had spent the last three years. There should have been family photos on the desk, scientists buzzing in the labs beneath, and, feet away, executives she knew and trusted, briefing her on potential cures for sickle cell disease and diabetes.

Instead, on that bone-chillingly cold day last spring, she was at a makeshift desk in the dimly lit basement of her home outside Boston, a bivouac chosen because it was closest to the Wifi router. Her closest companion was Ferris Bueller’s smug face on the wall and she spent the day jumping from Zoom call to Zoom call, worried less about making new drugs than making sure her employees were safe and that the global supply chain didn’t leave a cystic fibrosis patient without access to the Vertex pills that had changed their life. It was April 1, 2020.

“These are not what I thought would be the two of the highest priorities,” she tells me. “The safety of our people? You take it for granted.”

The pandemic hit Vertex at the worst possible time. Over the last decade, CEO Jeffrey Leiden, a jovial but shrewd and commanding figure, had pushed the development of those CF drugs, turning the most common fatal genetic disease in US and Europe into, for 90% of patients, a treatable condition. In the process, they had gone from a $6 billion to a $60 billion company and won the rare collective awe of the business, medical and patient communities. “I scream it from the rooftops,” says Bob Coughlin, former CEO of industry group MassBio, who’s 19-year-old son has CF. “He’s a whole new person, I’m filled with more gratitude than I’ve ever had in my whole damn life.”

Now, just as Leiden passed the torch, the entire world was collapsing. It was a trial by wildfire for Kewalramani, who had already been an unlikely choice as CEO. The heads of large biotechs are almost exclusively businesspeople, executives whose chief job is to sell the drugs the company has already developed and find other companies to acquire. If they have MDs, they also have an MBA or 20 years of experience in sales. All, historically, have been men.

Kewalramani was a clear-eyed, affable physician who had trained at Boston’s most prestigious hospitals and spent 12 years running trials at Amgen, but she had little experience on the business side of biotech. For the prior three years, leading Vertex’s medical team, she stood opposite the executive committee at key moments, explaining results from trials she designed and ran in sickle cell and cystic fibrosis.

“She came from the medical side, which was unique,” says Terry McGuire, founder and general partner of the Boston-based biotech VC Polaris Partners. “It speaks to their desire to really focus on what’s going on in the clinic and for patients.” Indeed, Vertex had only considered physician-scientists for the role. They had big plans for the role — for what they called Vertex 3.0. Although they had become known as the CF company, for years, Leiden told anyone who would listen that he didn’t just want to transform one disease: He planned to use the lavish proceeds from those pills to cure CF completely and either cure or defang an Infernal Council of famous ailments: Sickle cell disease, diabetes, muscular dystrophy and pain, among others.

It was as ambitious a plan as a biotech had ever put forward, spanning medical disciplines from hematology to nephrology and technologies from old-fashioned pills to new forms of CRISPR gene editing, and they needed someone with unimpeachable scientific chops to carry it out. If Kewalramani and her team can, they will change the face of medicine: Not just for one rare disease but several, and a few not so rare ones as well. They could also set off the same string of rancorous global debates that have followed Vertex’s CF drugs, as the company charged more than what many countries said they could pay. Kewalramani, while striking a less abrasive tone than her predecessor, has pledged to keep the same pricing strategy moving forward.

“We’re going to do what we did in CF,” Kewalramani tells me, echoing a promise she makes repeatedly. “Again and again and again.” But first they would have to deal with Covid-19.

As Kewalramani began her tenure as CEO, Vertex’s glimmering Seafront headquarters sat largely empty, as Boston faced the height of the early pandemic

Click on the image to see the full-sized version

Vertex has never been short on ambition. Kewalramani likes to tell the story of her first day at the company, in 2016. She was still an executive at Amgen, flown across the country to interview with a firm she knew little about, except that they invented Kalydeco, a powerful CF drug but one that worked for only 4% of patients. There was little data to suggest they could do the same for the other 96%, but when she sat down with Leiden and other executives, one by one they looked her in the eye and said, “We’re going to cure CF” — “without flinching, without looking down, without hedging,” she recalls.

Cures are so rarely delivered that drug executives can be loath to even utter ‘the C word,’ for fear they’ll be accused offering false hope, but it didn’t come across as bluster to Kewalramani. “I’ve not heard that kind of vision before,” she says. “That’s a pretty big statement: We’re going to cure a disease. And I believed them. I believed that this was the kind of company that would do that, and I wanted to be a part of it.”

Joshua Boger

Joshua BogerAnother way of looking at it is hubris, but Vertex has rarely minded that either. “Vertex is entirely driven by hubris,” longtime CTO Mark Mucko remarked in 1991. The company was founded in 1989 by Joshua Boger, a whiz-kid chemist at Merck who disdained the bureaucracy and conservatism endemic to big pharma, their preference for quick-to-market drugs that offered only marginal improvements, and believed he could do more with two chemists — and some then-cutting edge technology — than his deep-pocketed rivals could do with 200. “Arrogance doesn’t disturb or impress us,” he said once. “We understand arrogance.”

Arrogance served Vertex well, until it didn’t. Scientific achievements came: They cracked the structures of crucial proteins and published them in Cell and Nature, and they developed a potent AIDS antiviral, albeit one that came in gargantuan, unswallowable pills no one bought. Their big success was supposed to be Incivek, a hepatitis C antiviral that launched in 2011 and sold faster than any drug in history. But it wasn’t a cure and, within months, it became clear that a rival approach — one that Vertex derided and dismissed for years — would essentially be. Sales dried up. Layoffs eventually followed. Leiden, who joined the board in 2009 and became CEO amid the crisis, was later asked how Vertex failed. He responded, “hubris.”

The company Kewalramani interviewed at was in some ways a company reborn, even if they had never lost that potent mix of scientific commitment and self-belief, boasting about how half of its executive committee had MDs or PhDs and upwards of 70% of the budget went to R&D — more than virtually any other large drugmaker. After Incivek’s fall, Leiden pivoted to cystic fibrosis, focusing on a program Vertex had acquired as an afterthought when they bought out another biotech in 2001.

They had kept the project going largely because the CF Foundation agreed to foot much of the bill, eventually committing nearly $200 million in the hope Vertex could fix the disease’s root cause. CF is caused by mutations in CFTR, a protein that regulates how salt and moisture traffic throughout the body. In patients, the protein is misfolded, salt and moisture don’t move properly, and their mucus becomes thick and slimy, mucking up the lungs and preventing the pancreas from releasing key enzymes for digestion.

Vicki Sato

Vicki SatoThe foundation wanted Vertex to find a molecule that could refold the misfolded protein. It was a seemingly simple idea, but pharma companies had only ever used molecules to disable or, in a select few cases, activate a protein. Using one to refold a protein was a bit like trying to use bullets to heal a wound. “People thought we were crazy,” says Vicki Sato, CSO and then president of Vertex from 1992 to 2005. Yet by 2012, Kalydeco had reached patients. Kewalramani, head of nephrology at Amgen at the time, was so impressed that she added a slide about it to talks she gave about drug development: CF ranked among the most famously intractable disorders; researchers tried and failed to treat it for decades. “I was very inspired by that story,” she says.

Kewalramani would contribute to it. She took the job four days after the visit, leaving behind a dream home she built less than a year before with her husband and twin boys near Amgen’s California headquarters, and set about building it anew. Kalydeco worked for the 4% of patients whose proteins were misshapen in such a way they could be fixed with a single molecule. Within months of Kewalramani’s hiring, Vertex had early data to suggest that, for most patients, a combination of three molecules could be just as potent for 90% of patients. Kewalramani designed and ran the trials that would prove it, presenting the results to the executive committee two years after she arrived.

On March 31, 2019 Rachel Olimb was sitting in her living room in Phoenix when the phone rang. It was her husband, Jeremy. The Olimbs had lost one kid and had two other boys, Asher and Beck, under 12 with CF — boys the doctors said could expect to live to 36. But Jeremy said Vertex had just made an announcement: The triple-combo worked, improving lung function by 10% for 90% of patients, a level that could allow many to lead healthy lives. “They both cried for minutes, gushing tears on opposite ends of the line. “We felt like wow this is it, this is here,” Olimb told me. “This is the moment we’ve fought for, this is the moment where everything changes.”

In 2015, CEO Jeff Leiden and CSO David Altshuler devised a strategy to allow Vertex to repeat their success in CF in a series of diseases. They said it was different than anything else in the industry. (Photo by Barry Chin/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Click on the image to see the full-sized version

Everything changed for Vertex, as well. The company Kewalramani soon inherited would have to become something new. For a decade, despite occasional financial woes, Vertex dedicated itself to CF, building sophisticated cell models of disease, synthesizing tens of thousands of molecules and running dozens of trials. Now, they had taken the approach nearly as far as they could — the last 10% of CF patients have mutations that can’t be fixed by small molecules, either because make no proteins or proteins so garbled they can’t be saved — and were all but guaranteed $6 billion per year of revenue for over a decade. But what to do with it?

Historically, this is where most pharma companies fail. For all the talk of high drug prices funding future innovation, repeat success is vanishingly rare in biopharma, visited only on the couple companies who got lucky or, more recently, managed to master a particular disease or technology and then apply the skill repeatedly. (Think Regeneron, who, spent two decades struggling to develop a way of making antibodies, but have now produced 8 in the last 12 years, for cancer, Covid-19, Ebola, eczema, and heart disease, among other diseaes.) Knowing this, most large biotechs just buy their drugs from smaller companies.

But in 2015, famed geneticist Davild Altschuler, recently lured to Vertex as CSO, stood up at an all-2000-employees meeting and outlined a different strategy. They wouldn’t become masters of any of technology or disease, but instead be jack of all of them and master of something far more nebulous. Most drugs, he and Leiden concluded, failed simply because they were aimed at the wrong target. Think Alzheimer’s, where companies have spent, collectively, 20 years, billions of dollars and hundreds of failed attempts going after the same protein, without clear evidence it causes the devastating condition. So Vertex would become experts in picking the right targets. They would only go after serious diseases — “we’ll never make a drug for baldness,” as Leiden put it to me — where there was a clear target, usually a gene, that if you knocked out, modified or activated, you were nearly guaranteed to have an impact. The target had to be measurable, so you could tell quickly, both in lab models and in humans, whether the drug’s working. And the target had to be in “specialty markets” — diseases where you didn’t have to spend much on marketing, so they could continue to pour 70% of their expenses on R&D. They would then develop or acquire whatever technology was required to hit it.

Vertex previously had a mishmash of programs, drugs like VX-765 that had been studied for everything: Alzheimer’s, epilepsy, heart attack, arthritis, psoriasis. By Kewalramani’s first day in February, 2017, VX-765 was in the freezer and the company had jettisoned their cancer molecules to Merck KGaA, dropping out of a disease with often high sales costs. They signed a gene editing collaboration with CRISPR Therapeutics to search for cures for cystic fibrosis and sickle cell disease, and revved up internal programs in pain, AAT — a rare lung and liver disease caused, like CF, by a misshapen protein — and a form of kidney disease caused by a specific genetic mutation called APOL1.

Those programs, Kewalramani says, are a key part of what made her join. “I felt like I had just gotten to see something pretty amazing,” she says, “Everybody else was unaware of this, that there was this big pipeline behind CF.”

Doug Melton

Doug MeltonIn the months before Kewalramani was named CEO, Vertex burnished that pipeline with two moves. At a Mass General board meeting in April, Altshuler ran into Doug Melton, the Gilead co-founder and Harvard biologist, who produced from his briefcase a thumb-sized vial containing what looked like black caviar suspended in water. He explained that his company, Semma, had finally figured out how to synthetically produce the insulin-producing cells that are destroyed in type 1 diabetes patients and needed money to put them into humans as a would-be cure. “He said, ‘you know, we’ve been talking about this but we didn’t know it was that far along. Could I take that vial back to Vertex?” Melton recalls. Within six weeks, they had agreed in principle on a nearly $1 billion buyout.

Around the same time, Leiden called up UT Southwestern professor Eric Olson, an old friend who was working on a gene editing cure for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pfizer, Sarepta and Solid Bio were all racing to develop a gene therapy for the fatal muscle-wasting disease, but Leiden and Olson wondered how effective they would be. Gene therapy for DMD always faced a problem: The gene in DMD, dystrophin, is too long to fit inside the harmless viruses used to shuttle into humans, so researchers relied on a shortened version of the gene only ⅓ its size, called micro-dystrophin, that could. But would micro-dystrophin work as well as dystrophin? Dystrophin is a molecular shock-absorber, lining muscle cells and cushioning the stress of every contraction. No one knew if their mini shock absorber could handle the stress.

Eric Olson UT Southwestern

Eric Olson UT Southwestern Starting in 2012, Olson tried using CRISPR to build an alternative system to fix the mutant full-length gene patients already have, and, by 2019, showed it worked in dogs. He hadn’t planned on selling his company, Exonics, but he knew the hurdles they faced and what Vertex had done in CF — a genetic disease, like DMD, that had resisted every effort to treat it. He agreed to a $245 million buyout that June. “I felt like they knew the whole psychology around attacking these disorders,” he says.

The lab-grown insulin-producing cells Melton showed Altshuler. After 30 years in academic development, Vertex is hoping to place them into diabetes patients for the first time later this year, as a possible cure

Click on the image to see the full-sized version

By that time, Vertex had already been searching for a new CEO for nearly a year. Leiden was nearing the end of his career when he entered the role and, as Trikafta’s approval neared, he was looking for someone to lead the next phase: a physician-scientist who knew and believed Vertex’s strategy and could communicate it to both employees and the world. “And the more we looked, the more it became clear to us,” Leiden says. “She basically checked all the boxes.”

Kewalramani was as scientifically pedigreed as a drug executive came. She was born in Mumbai, back when it was known as Bombay, and at age 11 emigrated with her parents to Boston, where she says she learned a level of resilience and self-reliance struggling to fit in a school where no one could understand her accent. As she grew older, she jokes her parents gave her few options for the future. “I come from a good Indian family,” she says. “There’s only a few professions our families are happy with. Medicine is definitely one of them. Engineering is another common one. And I tell people the priesthood is a third, and I was not going to become a priest or an engineer.”

Fortunately, she was a self-described geek and after becoming a Westinghouse semi-finalist and going to a seven-year med school program at Boston University, she went for nephrology residency at MGH, relishing a field that relied on deduction rather than memorization. There was also a contrarian streak: “I also liked the fact that people really disliked nephrology,” she says. “It scared them, I thought it was cool.” Colleagues remembered her as particularly attentive and responsible. “She cared deeply about the patients entrusted in her care,” says Sekar Kathiresan, now CEO at Verve. “And that, I think, is emblematic of the kind of success she’s had over the years.”

Moving to Brigham and Women’s for a research fellowship, Kewalramani had plans to go into academic medicine, seeing patients once-a-week, but she didn’t meld perfectly with the nuts and bolts of lab work: She’d sweat profusely over mouse cages, she recalled last fall, and went to elaborate means to avoid touching them, including buying long tweezers or simply anesthetizing the rodents any time they had to be handled, a sometimes fatal resort. Despite her trepidation, the research was going well. But she also felt isolated in the lab and wondered if there was a way to have a more direct impact on patients. In 2004, she got a call from an Amgen headhunter, who happened to be the son of her department head at Brigham’s, and moved to California to help run kidney trials.

Those trials largely failed, as most trials do, but Tod Ibrahim, head of the American Society of Nephrology, says Kewalramani helped change kidney drug development. In 2010, he flew out to Amgen’s headquarters to meet with executives about how to bring to nephrology, long a pharmaceutical backwater, the advances that had come in areas like cancer and heart disease. Kewalramani told him they would need to spark new discoveries to get young researchers interested, while laying the clinical trial infrastructure for when those discoveries were ready for humans.

“She was going to go wherever she wanted to go, because she clearly stood out,” says Ibrahim. Her insights helped lead to the Kidney Health Initiative, an initiative that has boosted investment and helped accelerate kidney drugs. Kewalramani became a founding member and their go-to industry source. “She doesn’t say something unless she has something important to say,” Jonathan Himmelfarb, a nephrologist at the University of Washington who worked on the initiative, told me. “So she carries a lot of weight and authority, and she’s very strategic in the way that she thinks about things.”

When she joined Vertex, the company’s chemists had just synthesized the third molecule in Trikafta, and she spent most of her first years getting it to market. But as the pipeline progressed, she also designed trials for other therapies, including their gene editing therapy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia — the first company-sponsored CRISPR therapy to enter humans in the US since its 2011 discovery.

Vertex announced her role in July 2019, adding she would transition the following year. In October 2019, Kewalramani gathered Leiden and the executive committee to present the first sickle cell results. Although the data were early, she explained, all three patients appeared cured. “There was dead silence in the room for three or four minutes,” Leiden recalls. It changed his view of their post-CF work. “As we saw the sickle cell results — I mean, until then, it’s confidence in a concept, a dream,” he adds. “Now, it’s just the confidence is at a different level, because it’s proven, it’s a proven thing.”

Not everyone agrees Vertex’s pipeline is a proven thing. On investor calls throughout her first year, Kewalramani has faced constant questions about what Vertex might buy, a line of inquiry that betrays both gossip-column interest in how they’ll spend their treadmill of cash and a genuine critique that their pipeline is too thin. Kewalramani gives the same measured response each time — mid-stage drugs that fit their strategy, new technologies to help them hit new targets — I wonder if the questions ever grated.

“I assume positive intent,” Kewalramani says after a moment, noting it’s her job to explain the company’s strategy. “It does help to assume positive intent,” she said again, chuckling, “but I do assume that.”

For SVB Leerink analyst Geoffrey Porges, who has followed the company since 2003, much of Vertex’s strategy amounts simply to an ill-advised wager that they can, as their founder and early employees believed, out-research the industry. Most comapnies, he says, look for de-risked targets. He notes Vertex now work on a smattering of difficult technologies, and rather than acquire clinical-stage drugs from smaller companies, most of their deals so far have been for a motley of high-risk, early-stage science: Next-generation vectors for gene therapy, mRNA that can target the lung, new CRISPR enzymes, small molecules that can manipulate RNA. Porges called it “hubris.”

Geoffrey Porges

Geoffrey Porges“It’s hard to see why they would have any greater chance of success than anyone else, because despite a view they sometimes have, Vertex hasn’t cornered the market on smart people in the industry, they don’t have a secret sauce on picking winners,” says Porges, who wants Vertex to spend $10 to $15 billion to buy a new slate of candidates. “It’s a little dangerous for companies like Vertex to believe their own mythology.”

Vertex insists Leiden brought in a new culture in 2012, but they’ve actively cultivated the view of themselves as the industry’s scientific vanguard. At the center of the image is the CF success, even if part of the credit goes to the previous company Vertex bought and the CF foundation for keeping it alive when many of Vertex’s own employees and much of its board mocked or disdained it it. Kewalramani and colleagues refer repeatedly to the five drugs the company has brought from lab to market — a number, they note, puts them among only a tiny handful of drugmakers. And they talk about “serial innovation,” without a trace of the irony that now often follows the phrase in Silicon Valley.

“I appreciate the honesty of your question,” Kewalramani said when I raised Porges’ critique. “I couldn’t disagree more with the premise, and I’ll give you some facts.” In modifying a mutant protein, she said, the CF drugs represented that “was not known to science.” She pointed to their work on pain, where they showed proof-of-concept data on a target that large companies tried and failed to hit, and to their decision to work on CRISPR five years before it won a Nobel prize. She described their choice to go after sickle cell with a gene called BCL11A as “pure science” — a phrasing that irked UC Berkeley professor Fyodor Urnov, who noted that by 2015, academics had highlighted the target and both he and his former company, Sangamo, had described approaches to editing it. “I will admit I laughed out loud when I read the quote you sent,” he told me via email. (Vertex notes their strategy is unique and they were the first to put it in the clinic.)

Fyodor Urnov

Fyodor UrnovKewalramani said she wants Vertex to be the NASA of drug development: intense, science-heavy, relentless in pursuit of excellence. A former R&D employee, who spoke effusively about the culture, said that would trickle down to “moonshots” in individual departments, who would be encouraged to adopt whatever technology they needed to get there. “It’s really thinking big and being brave about it,” they said. Still, they found when they left there could be a downside to how intense or focused the climate was. “I kind of feel like I came out of my subterranean world, and was like, oh wow there actually is some interesting stuff going on,” they said. “When I was there, I really did believe that we were the only company doing anything interesting. And anything scientific, anything good.”

Porges’ view is far from universal. Melton said he had followed companies who buy a Phase III drug to look good to investors, but early-stage science was where one could make a large impact. “When I talked with Reshma, and Jeff,” he said, “I got the very strong feeling that they weren’t just trying to sell me on something where they could then get a quick fix that would make their balance sheet looked better.” Cowen’s Phil Nadeau called Vertex’s approach “rigorous and disciplined.”

George Scangos

George ScangosTerry McGuire, of Polaris, said he had seen that up close: In meetings with him or his companies, where other companies might ask what he had that was interesting, Vertex always knew exactly what they wanted. “Every biotech company thinks they do world-class science, most of them do not,” George Scangos, CEO of Vir and former CEO of Biogen, told me. “There’s a couple companies that I think do extraordinary research and drug development and make world-class drugs. I would put Vertex in that category.”

Yet the approach is still risky. A longtime executive noted that Vertex was trying to do something few, if any other biotechs had: Execute across technologies, such as cell and gene therapy, where the technical hurdles are extraordinary and routinely trip up companies dedicated solely to them.

“Can you believe in any one modality, let alone two, let alone six? And I think for a lot of these modalities, as exciting as these are, the process and just the ability to manufacture that product at scale — that’s a totally different level of complexity,” they told me. “We never had to deal with that… but certainly Vertex will.

Web of Alliances Vertex’s strategy has relied heavily on outside partnerships to rely on technology. In a couple cases, Exonics and Semma, they boughtout full early-stage companies

Click on the image to see the full-sized version

As Vertex became a juggernaut, they also became, to some, a villain. The company priced Kalydeco at $294,000 and charged nearly the same for all three of the pills that followed, setting off tense standoffs with countries who refused to meet their price. Leiden sometimes responded in the most personal terms imaginable, once accusing UK Prime Minister Theresa May of a “lack of commitment to children and young people with this devastating disease” and pulling their trials out of France when the country refused to pay for one of the CF drugs. (Both countries eventually struck a deal.)

Kewalramani is less caustic or openly antagonstic, and there’s been some signs of change on the ground. Belinda Nell, an activist in South Africa who’s lobbied Vertex for years for access for her sister, says the company’s representatives have become more open in the last few months, a change she attributed to the pressure activists put on the company. Yet a spokesperson denied any policy had changed and Kewalramani pledged to keep the pricing approach the same, for CF and any future meds. It’s a matter of value, she said: Vertex doesn’t make copycat or lifestyle drugs, or even drugs that just offer marginal benefit. “If you see a Vertex medicine come forward, it is a transformative medicine, if not a curative therapy,” she says. “And that’s what I think society wants to pay for, I think that’s what patients want access to.”

“I must say this is one time when I wish a CEO would not keep her word,” Paul Quinton told me. A legendary CF researcher and a CF patient himself, Quinton became a vocal Vertex critic after they priced Kalydeco. He and other activists point not to the money Vertex re-invests in R&D but to Leiden’s pay packages, which at one point eclipsed $36 million in a year. Kewalramani’s compensation pales in comparison — in 2020, as CEO, she made barely half what Leiden did as executive chair — but, as the new head, activists now call her out by name in campaigns for wider access. Patients are “literally dying,” argues one public letter addressed to her.

Activists note that, although nearly every US patient has access to Trikafta, it is still not available everywhere, including in South Africa and in Australia, where a committee recently recommended against paying Vertex’s price. (Vertex says they are working to secure access around the world; they note that Trikafta was only approved in the US in 2019 and individual countries can have long processes for approval and reimbursement.) “They have a cash cow by the horns, and there hasn’t been any effort to relieve what I see as extortion of the CF population,” Quinton says. “I was dissapointed to hear she’s not going to change anything. She sounds like another Jeff Leiden, it doesn’t inspire a lot of optimism.”

What will happen if Vertex manages to bring another drug forward? As one-time treatments, their gene therapies will likely cost even more. Aaron Kesselheim, a bioethicist at Harvard, said the problem was that Vertex doesn’t actually always develop transformative drugs. Many of the debates were around Orkambi, a pill that worked for half of patients but improved lung function by only 3%. If Vertex actually develops a cure for diabetes or DMD, he said, countries will pay. Scangos, though, wondered how long the strategy could last, particularly as more companies follow Vertex’s lead and develop high-priced drugs for rare diseases. “I don’t know about the pricing of this over the long term,” he said. “No single disease in that category is common enough to put a huge burden on the healthcare system by itself, but as more come out, it could be. I don’t know how much longer that is sustainable.

Bob Coughlin, the CF dad and former industry lobbyist, defends Trikafta’s costs because of all the costs he’s already seen save. “How many times has Bobby been in the hospital since he got his medicine? Zero,” he says. For him, Trikafta has bought time — years of Bobby’s life — for Vertex to devise a cure. It will be years before we’ll know if Vertex can deliver one, for CF or any disease, but the pandemic offered a litmus test for their scientific savvy.

Bob Coughlin’s son, Bobby, receiving his first dose of Trikafta

Bob Coughlin’s son, Bobby, receiving his first dose of TrikaftaKewalramani is a journaler but although she started amid a once-in-a-century crisis, she says she wrote little that day about fear or nerves. The company sensed early the threat the virus posed, cancelling a leadership meeting in February and becoming the first major drugmaker to publicly drop out of a major investor conference on March 3. Behind the scenes, Altshuler and a small team of data scientists worked five to eight hours a day to build their own dashboard and track the cases and hospitalization data the government wasn’t. Kewalramani checked in twice per week. It was as if they lived in a different world than the big, troubled biotech across town, Biogen, who welcomed the pandemic with the country’s first major superspreader event: A leadership meeting that epidimologists now estimate rippled out to 300,000 Covid-19 cases over the following year.

“If you look at this in a very objective way, the crisis that we face — this is in essence, a health crisis. This is a crisis of infectious disease. It’s about understanding data. It’s about contact tracing,” Kewalramani told me last September. “This is not a tsunami, it’s not an earthquake, it’s not a cyber attack, right? And in that way, Vertex is uniquely qualified to deal with this: 70% of our people are MD or PhD or PharmD.” It wasn’t intended as a dis — we didn’t discuss Biogen — but it could’ve served just as well.

The second thing Vertex did that stood out was even more unique: Nothing. While nearly every major drugmaker jumped out to develop a vaccine or an antibody or joined a molecule-hunting coalition, Vertex limited their coronavirus efforts to lending out a few assays. A virus no one had ever seen before looked and smelled nothing like CF, and they weren’t about to get distracted chasing. “We know what we’re good at and we stick to it,” she says.

So Kewalramani made sure patients had their drugs and her employees were safe and then set about figuring what science could still move forward, albeit in a different form, even amid a national shutdown: Trials for new cystic fibrosis pills? Sure. A CRISPR sickle cell therapy that involves a bone-marrow transplant and days at a hospital? Impossible.

Meanwhile, the George Floyd protests forced the freshman CEO to reckon with her own position. When she was named successor, reporters noted she would be the first woman or woman of color CEO of a large biotech before they noted her resume, but Kewalramani hadn’t sought out the position of role model. “It is my desire to be the best CEO without having to be the qualifier of women CEO, or women of color CEO,” she says. Soon, though, emails, LinkedIn messages, and handwritten letters flooded in, telling her they saw she was CEO and it meant something to them or their niece or granddaughter. Multiple people sent potted plants.

“If we don’t have role models that look like us, you start to believe that it’s not possible,” she says. “So I am thinking a lot more about it than I ever have before, and I’m very proud to serve as a role model to other people of color and to women. I certainly hope that in another couple of years, it’s not all that interesting that I happen to be a woman of color.”

As the pandemic’s first wave waned, Kewalramani got back on track, hiring 600 employees to cover their new diseases and to staff the 256,000 square foot cell & gene therapy center they were building outside Boston. Kewalramani, Altshuler and Leiden, met every other week with Olson’s DMD team, debating single DNA letter differences between the various viruses they might use to deliver the CRISPR therapy. (Another issue with DMD gene therapies: It’s difficult to get viruses to muscle). “I haven’t seen that level of focus of top level management in a large biotech, really getting into the science,” Olson said. Kewalramani personally spearheaded efforts to prepare Melton’s insulin cells for human trials, ultimately getting clearance from the FDA in March.

Because of Kewalramani’s medical-focused resume, Leiden agreed to stay around for three years to lead business development, cell and gene therapy, government affairs and investor relations. The arrangement raised early concerns about who was really in charge, one that Leiden has worked hard to dispel. Kewalramani, in turn, dove into the details of SEC filings and reading books from other CEOs: longtime GE chief Jeff Immelt’s memoir, The Hot Seat, and From Around the Corner to Around the World from ex-Dunkin’ chief Robert Rosenberg. “She has a quiet confidence about her,” Melton said. “She’s very clear about what she knows and what she doesn’t know, there’s no pretension with her. So if you’re talking about some very detailed scientific thing, and she doesn’t know about it, she says, ‘that’s interesting, tell me about it.'”

In the fall, Vertex announced their first trial for AATD failed for safety issues. Kewalramani said they would test a second molecule — for most diseases, Vertex builds a stable of back-up options, to hedge their bets — but the buzz had been so strong in the run-up, that shares fell 20%, from $271 to $215, where it has remained since. “This stock is really trading as if that means they just can’t develop drugs anymore,” says Stifel’s Paul Matteis, who’s been bullish on Vertex.

In November and December, though, the company announced curative data from 11 patients with sickle cell and beta-thalassemia, while bluebird bio announced yet more delays in their hunt for approval for a rival gene therapy. Although outside experts say it’s too early to say, Vertex now thinks they can get the first sickle cell cure on the market.

In Duchenne, Vertex had trailed Pfizer and Sarepta for years, but in January, Sarepta said that, in its first controlled trial, their gene therapy failed to improve patients’ muscle or motor function. For Leiden, it was vindication of his entire approach to drug development. “They didn’t understand that the mini shock absorber they put on that car wasn’t going to be able to take big pot holes,” he says. “It’s really not so much about the technique, it’s about understanding the underlying science.”

The hurdles ahead are huge. Kewalramani is happy to enumerate them, even as she evinces little doubt in Vertex’s ability to surpass them: Can they manufacture their cell and gene therapies, overcoming pitfalls that have snared rivals for years? Can they hire expertise across numerous diseases? Can they focus? When she arrived, she jokes, the entire company’s goal that year was developing a new CF drug, Symdeko. Now, how many actually know which molecule is VX-125 and which is VX-999?

Individual therapies face their own Achilles heels. For the diabetes therapy to hit more than a small portion of patients, they will have to figure out a way to encase the cells and shield it from the immune system. But most previous such efforts failed, said JDRF chief scientist Sanjoy Dutta. Although bluebird’s safety delay gave Vertex an upper hand, they also raised broader concerns around all sickle cell gene therapies, both analysts and researchers say.

Matteis said the next data he’s looking for is from their second AATD molecule, due out any day. Data on molecules for pain and kidney disease and the diabetes cell therapy will follow in 2022. “This year is huge,” he says. Still, he tried to caution against expecting Vertex from repeating what they did in CF: “As an analyst, I don’t think that’s the bar.” But that’s exactly where Kewalramani and Vertex have placed it.

“I think we can say we transformed CF — if we can do that for one more disease, two more diseases, gosh, if we could do that for three more diseases? That is unprecedented, and we have the chance to do it in five, six, seven, eight diseases,” she says. “So I don’t think that every single program will work, but importantly, not every single program has to.”

vaccine fda genetic antibodies therapy rna dna pandemic coronavirus covid-19 africa europe uk franceInternational

Red Candle In The Wind

Red Candle In The Wind

By Benjamin PIcton of Rabobank

February non-farm payrolls superficially exceeded market expectations on Friday by…

By Benjamin PIcton of Rabobank

February non-farm payrolls superficially exceeded market expectations on Friday by printing at 275,000 against a consensus call of 200,000. We say superficially, because the downward revisions to prior months totalled 167,000 for December and January, taking the total change in employed persons well below the implied forecast, and helping the unemployment rate to pop two-ticks to 3.9%. The U6 underemployment rate also rose from 7.2% to 7.3%, while average hourly earnings growth fell to 0.2% m-o-m and average weekly hours worked languished at 34.3, equalling pre-pandemic lows.

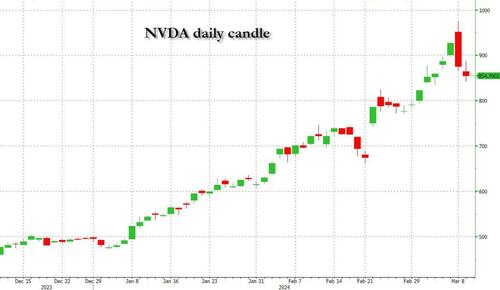

Undeterred by the devil in the detail, the algos sprang into action once exchanges opened. Market darling NVIDIA hit a new intraday high of $974 before (presumably) the humans took over and sold the stock down more than 10% to close at $875.28. If our suspicions are correct that it was the AIs buying before the humans started selling (no doubt triggering trailing stops on the way down), the irony is not lost on us.

The 1-day chart for NVIDIA now makes for interesting viewing, because the red candle posted on Friday presents quite a strong bearish engulfing signal. Volume traded on the day was almost double the 15-day simple moving average, and similar price action is observable on the 1-day charts for both Intel and AMD. Regular readers will be aware that we have expressed incredulity in the past about the durability the AI thematic melt-up, so it will be interesting to see whether Friday’s sell off is just a profit-taking blip, or a genuine trend reversal.

AI equities aside, this week ought to be important for markets because the BTFP program expires today. That means that the Fed will no longer be loaning cash to the banking system in exchange for collateral pledged at-par. The KBW Regional Banking index has so far taken this in its stride and is trading 30% above the lows established during the mini banking crisis of this time last year, but the Fed’s liquidity facility was effectively an exercise in can-kicking that makes regional banks a sector of the market worth paying attention to in the weeks ahead. Even here in Sydney, regulators are warning of external risks posed to the banking sector from scheduled refinancing of commercial real estate loans following sharp falls in valuations.

Markets are sending signals in other sectors, too. Gold closed at a new record-high of $2178/oz on Friday after trading above $2200/oz briefly. Gold has been going ballistic since the Friday before last, posting gains even on days where 2-year Treasury yields have risen. Gold bugs are buying as real yields fall from the October highs and inflation breakevens creep higher. This is particularly interesting as gold ETFs have been recording net outflows; suggesting that price gains aren’t being driven by a retail pile-in. Are gold buyers now betting on a stagflationary outcome where the Fed cuts without inflation being anchored at the 2% target? The price action around the US CPI release tomorrow ought to be illuminating.

Leaving the day-to-day movements to one side, we are also seeing further signs of structural change at the macro level. The UK budget last week included a provision for the creation of a British ISA. That is, an Individual Savings Account that provides tax breaks to savers who invest their money in the stock of British companies. This follows moves last year to encourage pension funds to head up the risk curve by allocating 5% of their capital to unlisted investments.

As a Hail Mary option for a government cruising toward an electoral drubbing it’s a curious choice, but it’s worth highlighting as cash-strapped governments increasingly see private savings pools as a funding solution for their spending priorities.

Of course, the UK is not alone in making creeping moves towards financial repression. In contrast to announcements today of increased trade liberalisation, Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmers has in the recent past flagged his interest in tapping private pension savings to fund state spending priorities, including defence, public housing and renewable energy projects. Both the UK and Australia appear intent on finding ways to open up the lungs of their economies, but government wants more say in directing private capital flows for state goals.

So, how far is the blurring of the lines between free markets and state planning likely to go? Given the immense and varied budgetary (and security) pressures that governments are facing, could we see a re-up of WWII-era Victory bonds, where private investors are encouraged to do their patriotic duty by directly financing government at negative real rates?

That would really light a fire under the gold market.

Government

Trump “Clearly Hasn’t Learned From His COVID-Era Mistakes”, RFK Jr. Says

Trump "Clearly Hasn’t Learned From His COVID-Era Mistakes", RFK Jr. Says

Authored by Jeff Louderback via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

President…

Authored by Jeff Louderback via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

President Joe Biden claimed that COVID vaccines are now helping cancer patients during his State of the Union address on March 7, but it was a response on Truth Social from former President Donald Trump that drew the ire of independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

During the address, President Biden said: “The pandemic no longer controls our lives. The vaccines that saved us from COVID are now being used to help beat cancer, turning setback into comeback. That’s what America does.”

President Trump wrote: “The Pandemic no longer controls our lives. The VACCINES that saved us from COVID are now being used to help beat cancer—turning setback into comeback. YOU’RE WELCOME JOE. NINE-MONTH APPROVAL TIME VS. 12 YEARS THAT IT WOULD HAVE TAKEN YOU.”

An outspoken critic of President Trump’s COVID response, and the Operation Warp Speed program that escalated the availability of COVID vaccines, Mr. Kennedy said on X, formerly known as Twitter, that “Donald Trump clearly hasn’t learned from his COVID-era mistakes.”

“He fails to recognize how ineffective his warp speed vaccine is as the ninth shot is being recommended to seniors. Even more troubling is the documented harm being caused by the shot to so many innocent children and adults who are suffering myocarditis, pericarditis, and brain inflammation,” Mr. Kennedy remarked.

“This has been confirmed by a CDC-funded study of 99 million people. Instead of bragging about its speedy approval, we should be honestly and transparently debating the abundant evidence that this vaccine may have caused more harm than good.

“I look forward to debating both Trump and Biden on Sept. 16 in San Marcos, Texas.”

Mr. Kennedy announced in April 2023 that he would challenge President Biden for the 2024 Democratic Party presidential nomination before declaring his run as an independent last October, claiming that the Democrat National Committee was “rigging the primary.”

Since the early stages of his campaign, Mr. Kennedy has generated more support than pundits expected from conservatives, moderates, and independents resulting in speculation that he could take votes away from President Trump.

Many Republicans continue to seek a reckoning over the government-imposed pandemic lockdowns and vaccine mandates.

President Trump’s defense of Operation Warp Speed, the program he rolled out in May 2020 to spur the development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines amid the pandemic, remains a sticking point for some of his supporters.

Operation Warp Speed featured a partnership between the government, the military, and the private sector, with the government paying for millions of vaccine doses to be produced.

President Trump released a statement in March 2021 saying: “I hope everyone remembers when they’re getting the COVID-19 Vaccine, that if I wasn’t President, you wouldn’t be getting that beautiful ‘shot’ for 5 years, at best, and probably wouldn’t be getting it at all. I hope everyone remembers!”

President Trump said about the COVID-19 vaccine in an interview on Fox News in March 2021: “It works incredibly well. Ninety-five percent, maybe even more than that. I would recommend it, and I would recommend it to a lot of people that don’t want to get it and a lot of those people voted for me, frankly.

“But again, we have our freedoms and we have to live by that and I agree with that also. But it’s a great vaccine, it’s a safe vaccine, and it’s something that works.”

On many occasions, President Trump has said that he is not in favor of vaccine mandates.

An environmental attorney, Mr. Kennedy founded Children’s Health Defense, a nonprofit that aims to end childhood health epidemics by promoting vaccine safeguards, among other initiatives.

Last year, Mr. Kennedy told podcaster Joe Rogan that ivermectin was suppressed by the FDA so that the COVID-19 vaccines could be granted emergency use authorization.

He has criticized Big Pharma, vaccine safety, and government mandates for years.

Since launching his presidential campaign, Mr. Kennedy has made his stances on the COVID-19 vaccines, and vaccines in general, a frequent talking point.

“I would argue that the science is very clear right now that they [vaccines] caused a lot more problems than they averted,” Mr. Kennedy said on Piers Morgan Uncensored last April.

“And if you look at the countries that did not vaccinate, they had the lowest death rates, they had the lowest COVID and infection rates.”

Additional data show a “direct correlation” between excess deaths and high vaccination rates in developed countries, he said.

President Trump and Mr. Kennedy have similar views on topics like protecting the U.S.-Mexico border and ending the Russia-Ukraine war.

COVID-19 is the topic where Mr. Kennedy and President Trump seem to differ the most.

Former President Donald Trump intended to “drain the swamp” when he took office in 2017, but he was “intimidated by bureaucrats” at federal agencies and did not accomplish that objective, Mr. Kennedy said on Feb. 5.

Speaking at a voter rally in Tucson, where he collected signatures to get on the Arizona ballot, the independent presidential candidate said President Trump was “earnest” when he vowed to “drain the swamp,” but it was “business as usual” during his term.

John Bolton, who President Trump appointed as a national security adviser, is “the template for a swamp creature,” Mr. Kennedy said.

Scott Gottlieb, who President Trump named to run the FDA, “was Pfizer’s business partner” and eventually returned to Pfizer, Mr. Kennedy said.

Mr. Kennedy said that President Trump had more lobbyists running federal agencies than any president in U.S. history.

“You can’t reform them when you’ve got the swamp creatures running them, and I’m not going to do that. I’m going to do something different,” Mr. Kennedy said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, President Trump “did not ask the questions that he should have,” he believes.

President Trump “knew that lockdowns were wrong” and then “agreed to lockdowns,” Mr. Kennedy said.

He also “knew that hydroxychloroquine worked, he said it,” Mr. Kennedy explained, adding that he was eventually “rolled over” by Dr. Anthony Fauci and his advisers.

MaryJo Perry, a longtime advocate for vaccine choice and a Trump supporter, thinks votes will be at a premium come Election Day, particularly because the independent and third-party field is becoming more competitive.

Ms. Perry, president of Mississippi Parents for Vaccine Rights, believes advocates for medical freedom could determine who is ultimately president.

She believes that Mr. Kennedy is “pulling votes from Trump” because of the former president’s stance on the vaccines.

“People care about medical freedom. It’s an important issue here in Mississippi, and across the country,” Ms. Perry told The Epoch Times.

“Trump should admit he was wrong about Operation Warp Speed and that COVID vaccines have been dangerous. That would make a difference among people he has offended.”

President Trump won’t lose enough votes to Mr. Kennedy about Operation Warp Speed and COVID vaccines to have a significant impact on the election, Ohio Republican strategist Wes Farno told The Epoch Times.

President Trump won in Ohio by eight percentage points in both 2016 and 2020. The Ohio Republican Party endorsed President Trump for the nomination in 2024.

“The positives of a Trump presidency far outweigh the negatives,” Mr. Farno said. “People are more concerned about their wallet and the economy.

“They are asking themselves if they were better off during President Trump’s term compared to since President Biden took office. The answer to that question is obvious because many Americans are struggling to afford groceries, gas, mortgages, and rent payments.

“America needs President Trump.”

Multiple national polls back Mr. Farno’s view.

As of March 6, the RealClearPolitics average of polls indicates that President Trump has 41.8 percent support in a five-way race that includes President Biden (38.4 percent), Mr. Kennedy (12.7 percent), independent Cornel West (2.6 percent), and Green Party nominee Jill Stein (1.7 percent).

A Pew Research Center study conducted among 10,133 U.S. adults from Feb. 7 to Feb. 11 showed that Democrats and Democrat-leaning independents (42 percent) are more likely than Republicans and GOP-leaning independents (15 percent) to say they have received an updated COVID vaccine.

The poll also reported that just 28 percent of adults say they have received the updated COVID inoculation.

The peer-reviewed multinational study of more than 99 million vaccinated people that Mr. Kennedy referenced in his X post on March 7 was published in the Vaccine journal on Feb. 12.

It aimed to evaluate the risk of 13 adverse events of special interest (AESI) following COVID-19 vaccination. The AESIs spanned three categories—neurological, hematologic (blood), and cardiovascular.

The study reviewed data collected from more than 99 million vaccinated people from eight nations—Argentina, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, New Zealand, and Scotland—looking at risks up to 42 days after getting the shots.

Three vaccines—Pfizer and Moderna’s mRNA vaccines as well as AstraZeneca’s viral vector jab—were examined in the study.

Researchers found higher-than-expected cases that they deemed met the threshold to be potential safety signals for multiple AESIs, including for Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), myocarditis, and pericarditis.

A safety signal refers to information that could suggest a potential risk or harm that may be associated with a medical product.

The study identified higher incidences of neurological, cardiovascular, and blood disorder complications than what the researchers expected.

President Trump’s role in Operation Warp Speed, and his continued praise of the COVID vaccine, remains a concern for some voters, including those who still support him.

Krista Cobb is a 40-year-old mother in western Ohio. She voted for President Trump in 2020 and said she would cast her vote for him this November, but she was stunned when she saw his response to President Biden about the COVID-19 vaccine during the State of the Union address.

“I love President Trump and support his policies, but at this point, he has to know they [advisers and health officials] lied about the shot,” Ms. Cobb told The Epoch Times.

“If he continues to promote it, especially after all of the hearings they’ve had about it in Congress, the side effects, and cover-ups on Capitol Hill, at what point does he become the same as the people who have lied?” Ms. Cobb added.

“I think he should distance himself from talk about Operation Warp Speed and even admit that he was wrong—that the vaccines have not had the impact he was told they would have. If he did that, people would respect him even more.”

International

There will soon be one million seats on this popular Amtrak route

“More people are taking the train than ever before,” says Amtrak’s Executive Vice President.

While the size of the United States makes it hard for it to compete with the inter-city train access available in places like Japan and many European countries, Amtrak trains are a very popular transportation option in certain pockets of the country — so much so that the country’s national railway company is expanding its Northeast Corridor by more than one million seats.

Related: This is what it's like to take a 19-hour train from New York to Chicago

Running from Boston all the way south to Washington, D.C., the route is one of the most popular as it passes through the most densely populated part of the country and serves as a commuter train for those who need to go between East Coast cities such as New York and Philadelphia for business.

Veronika Bondarenko

Amtrak launches new routes, promises travelers ‘additional travel options’

Earlier this month, Amtrak announced that it was adding four additional Northeastern routes to its schedule — two more routes between New York’s Penn Station and Union Station in Washington, D.C. on the weekend, a new early-morning weekday route between New York and Philadelphia’s William H. Gray III 30th Street Station and a weekend route between Philadelphia and Boston’s South Station.

More Travel:

- A new travel term is taking over the internet (and reaching airlines and hotels)

- The 10 best airline stocks to buy now

- Airlines see a new kind of traveler at the front of the plane

According to Amtrak, these additions will increase Northeast Corridor’s service by 20% on the weekdays and 10% on the weekends for a total of one million additional seats when counted by how many will ride the corridor over the year.

“More people are taking the train than ever before and we’re proud to offer our customers additional travel options when they ride with us on the Northeast Regional,” Amtrak Executive Vice President and Chief Commercial Officer Eliot Hamlisch said in a statement on the new routes. “The Northeast Regional gets you where you want to go comfortably, conveniently and sustainably as you breeze past traffic on I-95 for a more enjoyable travel experience.”

Here are some of the other Amtrak changes you can expect to see

Amtrak also said that, in the 2023 financial year, the Northeast Corridor had nearly 9.2 million riders — 8% more than it had pre-pandemic and a 29% increase from 2022. The higher demand, particularly during both off-peak hours and the time when many business travelers use to get to work, is pushing Amtrak to invest into this corridor in particular.

To reach more customers, Amtrak has also made several changes to both its routes and pricing system. In the fall of 2023, it introduced a type of new “Night Owl Fare” — if traveling during very late or very early hours, one can go between cities like New York and Philadelphia or Philadelphia and Washington. D.C. for $5 to $15.

As travel on the same routes during peak hours can reach as much as $300, this was a deliberate move to reach those who have the flexibility of time and might have otherwise preferred more affordable methods of transportation such as the bus. After seeing strong uptake, Amtrak added this type of fare to more Boston routes.

The largest distances, such as the ones between Boston and New York or New York and Washington, are available at the lowest rate for $20.

stocks pandemic japan european-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges