Government

How well did the Fed’s intervention in the municipal bond market work?

The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic strained many sectors of the economy, including the municipal bond market, prompting an unprecedented intervention by the Federal Reserve. This post summarizes the latest research on the effectiveness of the Fed’s…

By Sophia Campbell, David Wessel

The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic strained many sectors of the economy, including the municipal bond market, prompting an unprecedented intervention by the Federal Reserve. This post summarizes the latest research on the effectiveness of the Fed’s response to COVID-related distress in the muni market, which finances more than 50,000 local and state governments and other entities.

How did COVID-19 affect the muni bond market?

Prior to the pandemic, the muni market was ebullient. According to Morningstar, between the beginning of 2019 and February 2020, investors put $105 billion into muni mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, the largest annual influx in the muni sector in 25 years.

COVID-19 hit nearly every sector of the financial market. In the muni market, investors apparently feared that state and local government revenues would fall and spending would increase, hurting governments’ ability to service their debt.

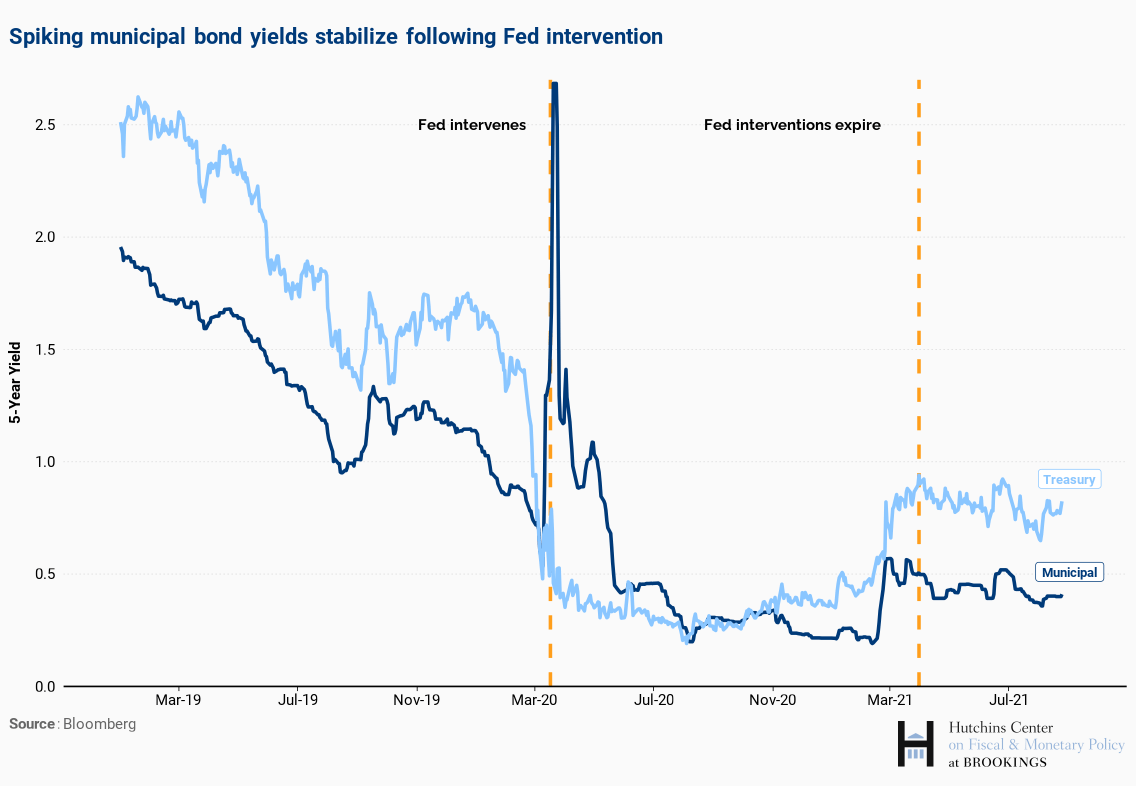

In March 2020, investors pulled a record $45 billion from muni funds. Municipal bond prices dropped, and the yield on muni bonds rose sharply above the yield on comparable U.S. Treasuries. The yield on muni bonds typically is about 80% of that of U.S. Treasury bonds, reflecting the fact that interest on the former is exempt from federal income taxes and interest on the latter is taxable. By the end of March, muni yields were nearly four times that of Treasuries.

With few investors willing to buy municipal securities, state and local governments struggled to borrow in the face of COVID-related budget constraints.

What did the Fed do?

During the Great Recession, the Federal Reserve did not intervene in the muni bond market, nor did it lend to state and local governments. The COVID-19 recession was different.

The $2.2 trillion CARES Act, passed by Congress early in the pandemic, provided $454 billion to the Treasury to be used to backstop Fed lending to businesses and state and local governments. In general, the Federal Reserve will lend only if it expects it will be paid back in full; the appropriation was intended to absorb any losses that the Fed incurred.

In March 2020, the Federal Reserve made municipal securities eligible for its Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) (meaning the Fed was willing to buy short-term muni debt directly from state and local governments) and for the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF) (meaning that the Fed would make loans to banks secured by municipal securities bought from money market mutual funds). Both actions were intended to stabilize municipal bond prices and state and local governments’ ability to borrow through the public health crisis. Both the MMLF and CPFF expired on March 31st, 2021.

In addition, the Fed launched the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) in April 2020 to lend up to $500 billion directly to states and local governments with populations above a certain threshold; the list of eligible borrowers was later expanded to include more issuers. However, only the state of Illinois and the New York MTA made use of the program, borrowing $3.2 billion and $3.36 billion, respectively. The MLF stopped lending on December 31st, 2020, after Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin withdrew Treasury support.

Did the Fed’s intervention work?

Fed intervention was intended to prevent the deepening COVID-19 recession from pushing up muni rates and starving state and local governments of cash. Within days of the Fed’s initial intervention in March 2020, muni yields began a sharp decline that would continue through the summer of 2020. By the time the CPFF and MMLF expired, muni rates sat at about 50% of Treasury rates and have remained there since.

Despite low take up of the Municipal Liquidity Facility, research suggests the availability of the program was quite effective at easing investors’ concerns and stabilizing muni bond yields. Based on the historical relationship between unemployment and muni bond rates, Michael D. Bordo of Rutgers and John V. Duca of the Dallas Fed estimate that muni yields could have risen by as much as 8 percentage points more than they did in mid-April had the Fed not launched the MLF on April 9. “That these effects occurred far in advance of the opening of the MLF and given the very modest borrowing by municipal entities at the MLF together imply that the announcement of this new facility had a pronounced and rapid backstop effect,” the authors say. “These results along with others imply that there was systemic risk in the muni bond market in the COVID-19 pandemic, that was not the case for the isolated, but prominent, muni defaults in the prior half century.”

In a paper presented at the Hutchins Center’s 10th Annual Municipal Finance Conference, Andrew Haughwout, Benjamin Hyman, and Or Shachar of the New York Fed show that the introduction of the MLF particularly lowered yields in the private market for low-rated issuers, and allowed local governments to more easily borrow money to retain employees despite falling revenues and higher spending due to the pandemic. By comparing issuers just below and above the population eligibility cutoff for the MLF, Haughwout and co-authors find that eligible low-rated issuers saw yields fall by about 72 basis points relative to comparable ineligible issuers. The higher gains from the MLF experienced by low-rated issuers, the authors hypothesize, imply that the MLF was seen as an indication of the Fed’s willingness to share credit risk by making loans available to struggling state and local governments.

Furthermore, Haughwout and co-authors show that in response to the improved muni market conditions and direct aid from the CARES Act, local governments eligible for the MLF retained 25% to 30% more service-providing employees, particularly in the education sector. High-rated government issuers recalled employees despite continued shutdowns—suggesting that the MLF option may have alleviated some of the uncertainty local governments faced at the start of the pandemic.

Huixin Bi and W. Blake Marsh of the Kansas City Fed investigate whether the increases in muni bond yields at the onset of the COVID crisis reflect overall liquidity risk (concern that a muni bond would be difficult to sell quickly without a substantial decline in price) or local credit risk (concern that counties with high COVID cases per capita would not be able to pay their debts on time). The authors compare yields on pre-funded bonds (which are essentially backed by Treasuries and so not much affected by credit risk concerns) to bonds that are not pre-funded. Movements in pre-refunded bond yields should reflect liquidity concerns, while changes in spreads between pre-refunded and not-pre-refunded bond yields should reflect credit risks. Observing that yields on both sets of bonds fell after Fed announcements, the authors conclude that policy interventions stabilized muni yields significantly by lowering liquidity risks, but didn’t immediate ease credit concerns—that is, worries that a prolonged economic downtown would make it difficult to governments to pay debt service on time.

Bi and Marsh also find that credit risks were an important component of short-term muni bond yields at the start of the pandemic. Following Fed interventions (which largely targeted short-term debt), credit concerns eased for short-term debt but became more pronounced for long-term debt.

The Fed did not intervene in the secondary market for muni bonds, as it did in the secondary market for corporate bonds. Yi Li and Xing (Alex) Zhou of the Federal Reserve Board and Maureen O’Hara of Cornell University argue that this lack of intervention prolonged fragility in the market for municipal bonds held by mutual funds. At the start of the crisis, secondary market dealers stopped buying and started selling muni bonds held by mutual funds, and continued to do so even after the Fed’s interventions stabilized the muni market—leaving a lingering spread of about 30 basis points, a “fire sale premium,” between bonds held by mutual funds and those that were not.

In the corporate bond market, however, which also saw large outflows from mutual funds at the start of the crisis, the announcement of the Fed’s Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility offered reassurance to dealers that the Fed would purchase secondary market corporate bonds and stabilize liquidity in the market. Mutual fund outflows reversed, and soon returned to their pre-pandemic levels. With no such reassurance from the Fed, Li and co-authors argue, dealers in the muni market continued to sell bonds carrying mutual fund risks and the “fire sale premium” persisted.

recession unemployment pandemic covid-19 treasury bonds municipal bonds bonds corporate bonds fed federal reserve treasury rates mnuchin congress spread recession unemploymentGovernment

Low Iron Levels In Blood Could Trigger Long COVID: Study

Low Iron Levels In Blood Could Trigger Long COVID: Study

Authored by Amie Dahnke via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

People with inadequate…

Authored by Amie Dahnke via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

People with inadequate iron levels in their blood due to a COVID-19 infection could be at greater risk of long COVID.

A new study indicates that problems with iron levels in the bloodstream likely trigger chronic inflammation and other conditions associated with the post-COVID phenomenon. The findings, published on March 1 in Nature Immunology, could offer new ways to treat or prevent the condition.

Long COVID Patients Have Low Iron Levels

Researchers at the University of Cambridge pinpointed low iron as a potential link to long-COVID symptoms thanks to a study they initiated shortly after the start of the pandemic. They recruited people who tested positive for the virus to provide blood samples for analysis over a year, which allowed the researchers to look for post-infection changes in the blood. The researchers looked at 214 samples and found that 45 percent of patients reported symptoms of long COVID that lasted between three and 10 months.

In analyzing the blood samples, the research team noticed that people experiencing long COVID had low iron levels, contributing to anemia and low red blood cell production, just two weeks after they were diagnosed with COVID-19. This was true for patients regardless of age, sex, or the initial severity of their infection.

According to one of the study co-authors, the removal of iron from the bloodstream is a natural process and defense mechanism of the body.

But it can jeopardize a person’s recovery.

“When the body has an infection, it responds by removing iron from the bloodstream. This protects us from potentially lethal bacteria that capture the iron in the bloodstream and grow rapidly. It’s an evolutionary response that redistributes iron in the body, and the blood plasma becomes an iron desert,” University of Oxford professor Hal Drakesmith said in a press release. “However, if this goes on for a long time, there is less iron for red blood cells, so oxygen is transported less efficiently affecting metabolism and energy production, and for white blood cells, which need iron to work properly. The protective mechanism ends up becoming a problem.”

The research team believes that consistently low iron levels could explain why individuals with long COVID continue to experience fatigue and difficulty exercising. As such, the researchers suggested iron supplementation to help regulate and prevent the often debilitating symptoms associated with long COVID.

“It isn’t necessarily the case that individuals don’t have enough iron in their body, it’s just that it’s trapped in the wrong place,” Aimee Hanson, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge who worked on the study, said in the press release. “What we need is a way to remobilize the iron and pull it back into the bloodstream, where it becomes more useful to the red blood cells.”

The research team pointed out that iron supplementation isn’t always straightforward. Achieving the right level of iron varies from person to person. Too much iron can cause stomach issues, ranging from constipation, nausea, and abdominal pain to gastritis and gastric lesions.

1 in 5 Still Affected by Long COVID

COVID-19 has affected nearly 40 percent of Americans, with one in five of those still suffering from symptoms of long COVID, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Long COVID is marked by health issues that continue at least four weeks after an individual was initially diagnosed with COVID-19. Symptoms can last for days, weeks, months, or years and may include fatigue, cough or chest pain, headache, brain fog, depression or anxiety, digestive issues, and joint or muscle pain.

Government

Walmart joins Costco in sharing key pricing news

The massive retailers have both shared information that some retailers keep very close to the vest.

As we head toward a presidential election, the presumed candidates for both parties will look for issues that rally undecided voters.

The economy will be a key issue, with Democrats pointing to job creation and lowering prices while Republicans will cite the layoffs at Big Tech companies, high housing prices, and of course, sticky inflation.

The covid pandemic created a perfect storm for inflation and higher prices. It became harder to get many items because people getting sick slowed down, or even stopped, production at some factories.

Related: Popular mall retailer shuts down abruptly after bankruptcy filing

It was also a period where demand increased while shipping, trucking and delivery systems were all strained or thrown out of whack. The combination led to product shortages and higher prices.

You might have gone to the grocery store and not been able to buy your favorite paper towel brand or find toilet paper at all. That happened partly because of the supply chain and partly due to increased demand, but at the end of the day, it led to higher prices, which some consumers blamed on President Joe Biden's administration.

Biden, of course, was blamed for the price increases, but as inflation has dropped and grocery prices have fallen, few companies have been up front about it. That's probably not a political choice in most cases. Instead, some companies have chosen to lower prices more slowly than they raised them.

However, two major retailers, Walmart (WMT) and Costco, have been very honest about inflation. Walmart Chief Executive Doug McMillon's most recent comments validate what Biden's administration has been saying about the state of the economy. And they contrast with the economic picture being painted by Republicans who support their presumptive nominee, Donald Trump.

Image source: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Walmart sees lower prices

McMillon does not talk about lower prices to make a political statement. He's communicating with customers and potential customers through the analysts who cover the company's quarterly-earnings calls.

During Walmart's fiscal-fourth-quarter-earnings call, McMillon was clear that prices are going down.

"I'm excited about the omnichannel net promoter score trends the team is driving. Across countries, we continue to see a customer that's resilient but looking for value. As always, we're working hard to deliver that for them, including through our rollbacks on food pricing in Walmart U.S. Those were up significantly in Q4 versus last year, following a big increase in Q3," he said.

He was specific about where the chain has seen prices go down.

"Our general merchandise prices are lower than a year ago and even two years ago in some categories, which means our customers are finding value in areas like apparel and hard lines," he said. "In food, prices are lower than a year ago in places like eggs, apples, and deli snacks, but higher in other places like asparagus and blackberries."

McMillon said that in other areas prices were still up but have been falling.

"Dry grocery and consumables categories like paper goods and cleaning supplies are up mid-single digits versus last year and high teens versus two years ago. Private-brand penetration is up in many of the countries where we operate, including the United States," he said.

Costco sees almost no inflation impact

McMillon avoided the word inflation in his comments. Costco (COST) Chief Financial Officer Richard Galanti, who steps down on March 15, has been very transparent on the topic.

The CFO commented on inflation during his company's fiscal-first-quarter-earnings call.

"Most recently, in the last fourth-quarter discussion, we had estimated that year-over-year inflation was in the 1% to 2% range. Our estimate for the quarter just ended, that inflation was in the 0% to 1% range," he said.

Galanti made clear that inflation (and even deflation) varied by category.

"A bigger deflation in some big and bulky items like furniture sets due to lower freight costs year over year, as well as on things like domestics, bulky lower-priced items, again, where the freight cost is significant. Some deflationary items were as much as 20% to 30% and, again, mostly freight-related," he added.

bankruptcy pandemic trumpGovernment

Walmart has really good news for shoppers (and Joe Biden)

The giant retailer joins Costco in making a statement that has political overtones, even if that’s not the intent.

As we head toward a presidential election, the presumed candidates for both parties will look for issues that rally undecided voters.

The economy will be a key issue, with Democrats pointing to job creation and lowering prices while Republicans will cite the layoffs at Big Tech companies, high housing prices, and of course, sticky inflation.

The covid pandemic created a perfect storm for inflation and higher prices. It became harder to get many items because people getting sick slowed down, or even stopped, production at some factories.

Related: Popular mall retailer shuts down abruptly after bankruptcy filing

It was also a period where demand increased while shipping, trucking and delivery systems were all strained or thrown out of whack. The combination led to product shortages and higher prices.

You might have gone to the grocery store and not been able to buy your favorite paper towel brand or find toilet paper at all. That happened partly because of the supply chain and partly due to increased demand, but at the end of the day, it led to higher prices, which some consumers blamed on President Joe Biden's administration.

Biden, of course, was blamed for the price increases, but as inflation has dropped and grocery prices have fallen, few companies have been up front about it. That's probably not a political choice in most cases. Instead, some companies have chosen to lower prices more slowly than they raised them.

However, two major retailers, Walmart (WMT) and Costco, have been very honest about inflation. Walmart Chief Executive Doug McMillon's most recent comments validate what Biden's administration has been saying about the state of the economy. And they contrast with the economic picture being painted by Republicans who support their presumptive nominee, Donald Trump.

Image source: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Walmart sees lower prices

McMillon does not talk about lower prices to make a political statement. He's communicating with customers and potential customers through the analysts who cover the company's quarterly-earnings calls.

During Walmart's fiscal-fourth-quarter-earnings call, McMillon was clear that prices are going down.

"I'm excited about the omnichannel net promoter score trends the team is driving. Across countries, we continue to see a customer that's resilient but looking for value. As always, we're working hard to deliver that for them, including through our rollbacks on food pricing in Walmart U.S. Those were up significantly in Q4 versus last year, following a big increase in Q3," he said.

He was specific about where the chain has seen prices go down.

"Our general merchandise prices are lower than a year ago and even two years ago in some categories, which means our customers are finding value in areas like apparel and hard lines," he said. "In food, prices are lower than a year ago in places like eggs, apples, and deli snacks, but higher in other places like asparagus and blackberries."

McMillon said that in other areas prices were still up but have been falling.

"Dry grocery and consumables categories like paper goods and cleaning supplies are up mid-single digits versus last year and high teens versus two years ago. Private-brand penetration is up in many of the countries where we operate, including the United States," he said.

Costco sees almost no inflation impact

McMillon avoided the word inflation in his comments. Costco (COST) Chief Financial Officer Richard Galanti, who steps down on March 15, has been very transparent on the topic.

The CFO commented on inflation during his company's fiscal-first-quarter-earnings call.

"Most recently, in the last fourth-quarter discussion, we had estimated that year-over-year inflation was in the 1% to 2% range. Our estimate for the quarter just ended, that inflation was in the 0% to 1% range," he said.

Galanti made clear that inflation (and even deflation) varied by category.

"A bigger deflation in some big and bulky items like furniture sets due to lower freight costs year over year, as well as on things like domestics, bulky lower-priced items, again, where the freight cost is significant. Some deflationary items were as much as 20% to 30% and, again, mostly freight-related," he added.

bankruptcy pandemic trump-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges