International

How the future of shopping was shaped by its past

The pandemic changed the way we shop – with many ‘new’ initiatives actually reinventing old ways of doing things.

It’s a sunny, spring Saturday morning in early 2019 and I’m having coffee at the local Costa in Brentford, a small Essex town where I’ve never been before. There are plenty of people out and about and smiling. I have a couple of hours to spare so I’m planning to wander around and have a look in the shops. Then my phone pings: “Surprise!” It’s a promotion from M&S. “Here’s 20% off when you shop online”.

The Brentford branch of M&S is just a couple of doors down from where I am – I just passed it. But the notification isn’t suggesting I go there. On the contrary, this special offer will deter me from shopping in an actual shop, on an actual high street, where I know I’d now be paying 25% more (if you start from the lower price) than I would if I bought online. It is, in effect, a counter-advertisement – taking me away from the shops and towards a virtual, online-only future.

Around this time, M&S had been closing stores in numerous locations. Many of these shops had been there for as long as people could remember, and were part of the towns’ identity. Like “our” NHS, and unlike most other commercial brands, M&S evokes a feeling of belonging to a shared history.

Looking back, my little counter-epiphany now seems to encapsulate something of the fraught shopping mood of three years ago. The incident felt like a painful sign of the contradictory state of British retail – and especially that part of it that is commonly known as the high street.

The choice on offer was absurd for both the customers (only one rational way to go), and the company (why push customers away from the stores that are still in use?). But it was somehow feasible then, in those innocent pre-pandemic times, to take for granted the inevitable triumph of online retail, even if it brought with it the destruction of most other modes of buying and selling.

From street pedlars to supermarkets

Online shopping seemed in those days to be the next and natural step along the path that began with the introduction of self-service. I started charting these developments more than 20 years ago when I wrote Carried Away: The Invention of Modern Shopping. And a year after the sad Brentwood episode, at the start of 2020, I was coming to the end of writing my new book Back to the Shops: The High Street in History and the Future. This investigates the different stages of shopping, from its early beginnings to the present.

This history stretches back to pedlars and weekly markets and runs through small fixed shops in towns and villages to the grand “destination” city department stores of the last part of the 19th century. Then, in the later 20th century, came self-service, to be followed in recent years by the move online.

This story is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism and is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects to tackle societal and scientific challenges.

But shopping history never moves in one single direction or all at once. There have always been regional and chronological divergences from mainstream developments. There are also retailing modes that fall by the wayside and then return at a later date in new guises or with new names. They often have every appearance of being newly invented.

Take fast fashion, for instance. We think of fast fashion as inseparable from a contemporary culture of rapid turnover. But a version of it can be found as far back as the 18th century, well before garments were mass-produced in factories. Clothes at this time were all sewn by hand.

In late 18th century London, a new type of shop appeared where, for a price, a lady or gentleman could commission a customised outfit that would be made up for them overnight. It offered an instant transformation into the style and class of the best social circles. But unlike modern fast fashion, it wasn’t cheap and the clothes weren’t flimsy or soon discarded.

The same period also saw the arrival of short-term shops not unlike those that we now call pop-ups. They might appear in any village, when an itinerant salesman rented a room in the local pub as a temporary location for what he’d present as a flash sale: “now or never”. In the 1760s, for example, Thomas Turner, who kept the main shop in the small Sussex village of East Hoathly, complained in his diary about just such a character zooming into the area – and taking away attention, and trade, from his own steady service.

Today, pop-ups move into empty shop units on a short-term basis and at a lower-cost rental. It is a useful arrangement for both the owner of the premises and the shopkeeper. The landlord gets some (if not all) of their usual income for a space that would otherwise be yielding no income, while the tenant, with no long-term commitment, takes no great risk. The business itself – often selling time-limited, seasonal stock – is here today and gone soon after.

Mail order shopping also has a rich history that seems to anticipate later developments, too. Catalogue companies, like Freeman’s or Kay’s, were massively popular in the middle decades of the 20th century. But despite its popularity, “the book” (the affectionate name for the big, “full colour” catalogue) never posed a threat to the shops. Nevertheless, mail order was a form of virtual shopping at a distance, and now looks like a striking precursor to online shopping.

Perhaps the most surprising example of an early retail development whose beginnings have now disappeared from view, is the chain store. We tend to think of chain stores as having pushed independent shops out of the way in the late 20th century, with the result that every shopping mall and every high street (if it survives at all) looks like all the rest. But, in fact, chain stores were everywhere a century earlier, including some of the names that are still well known today.

Chains took off in the second half of the 19th century. Nationwide grocery companies like Lipton’s or Home & Colonial had thousands – yes, thousands – of branches by 1900. Of these early chains (or “multiples” as they were then called) only the Co-op remains. The Co-op no longer maintains the cultural and trading pre-eminence it had from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. But unlike the other dominant chains of that era, it has endured. It even pioneered the move to self-service in the middle of the 20th century and it remains a significant player among the biggest supermarket chains of today.

WHSmith, the newsagent and bookseller, developed from the late 1840s alongside the growing railway network. There was soon a stall to be seen inside every station of any size, providing the passenger with novels or newspapers for their journey. In 1900, there were no fewer than 800 branches nationwide. From the beginning of the 20th century, Smith’s also had outlets on town shopping streets.

Boots the chemist was another 19th-century chain that is still a standard high street presence. The first Boots shop was opened in Nottingham in 1849. By the turn of the century, there were around 250 branches – and 1,000 by the early 1930s.

Numerous small and large chains, selling many types of commodity, faded away, died their deaths, or were taken over. But the striking point is that chain store Britain is nothing new. It dates back well over a century.

The self-service revolution

If online retail was the new feature of early 21st century shopping, self-service was the shopping revolution of the 20th century.

Self-service reached Europe after the Second World war. In the US, it had been an accidental invention of the Great Depression, when abandoned factories and warehouses were turned into makeshift, cut-price outlets. Customers picked out goods as they walked around and paid for everything at the end. By the 1940s, this new type of store was well established, often in regional chains, as the “super market”. Postwar, this new American mode of retail operation was exported to the rest of the world.

Promoted as a modern, efficient way to shop, self-service entailed both a different type of store layout and new norms of customer and shopworker behaviour. Before this, every purchase made was asked for over the counter, item by item, and the assistant “served” the customer personally. Few goods were packaged, so every order was literally customised: measured or weighed and then wrapped.

But self-service did away with all this. There was no need for counter service if customers were making their own selections. All available goods were put out on display, within reach. No need to ask someone to fetch them. And there was no one else waiting behind you for their turn to be served. You could take your time, look around – or get it done at speed. It was your choice.

This was a newly impersonal shopping environment. The customer was in control of the pace and the selection, but they were on their own and there was no longer someone standing there to serve them. For shop workers, meanwhile, the abolition of counter service meant that their various skills, including their people skills, were made redundant. So too was their often detailed knowledge of the products they sold.

When the customer did encounter a person across a counter, it was not to ask for advice about what to buy; it was simply to pay and get out. Now they just handed over a basket of goods already picked out; the assistant was not involved in the choosing. Nor was the checkout for chatting. Like factory workers, cashiers had to keep up to speed.

The whole process was meant to be more efficient, a saving of time and money for the benefit of business and customers alike. The customer, notably, was seen now as someone for whom time was a finite and valuable resource. In this way the shift to self-service was perfectly matched with some large social changes of the postwar decades.

As late as the 1960s, for example, “housewife” was the default designation for women over the age of 16 (even though many had part- or full-time jobs). But the “housewife” would soon be replaced by the double-shift working woman, eternally “juggling” the demands of both home and work. By the end of the 20th century, now with the help of a fridge and a car, the daily walk to the local shops had been replaced by a weekly trip to the supermarket, where everything was available under one roof and the shopping was now a substantial task.

The first 1950s self-service stores are distant enough today to have become the subject of mild nostalgia, obscuring the original picture of smart efficiency. Black and white photos from the archives show people (particularly women) of every social type gamely learning to manage the curious “basket” containers provided for them to carry around on their arms and fill up as they walked around the shop. These shoppers are no longer standing or sitting at the counter while they wait for their turn and that, at the outset, was the visible difference introduced by self-service. What looks odd now, many decades later, is how little they’re buying – just a few jars and tins.

Save time online

With self-service firmly established to assist supposedly “time-poor” consumers, the stage was set for internet shopping to promise an even more efficient way of doing things.

An Ocado flyer from early 2019 displays the caption: “More time living, less time shopping”, as if living and shopping have become mutually exclusive. And crucially, it is not money but time – its saving or gaining – which is the quantifiable currency of the promotion.

In this way, the online upgrade appears to remove all remaining real-life interference from the task of shopping. You don’t have to take yourself anywhere to get to the store, which never closes. There are no empty shelves; everything is always there on the screen. There is still a trolley or basket, but not one that you have to push or carry, and it will hold whatever you “add” to it, irrespective of volume or quantity.

The shop assistant is wholly absent from the screen, although there are downgraded virtual versions available in the form of programmed chat-bots. With online shopping, the backstage work that “fulfils” an order occurs in a storage facility far away and is invisible to the customer. But in large self-service settings, like supermarkets and DIY mega-stores, the role of the checkout cashier had already been reduced to that single scanning function, requiring no specialist range of skills and no particular knowledge of any one of the thousands of possible things, from bananas to baby wipes, that they might be rapidly moving along.

Back to the ‘real’ shops?

Town centres had been dying a much discussed death for years, as more and more shops were being closed down – and stayed unused.

But amid the doom and gloom, some towns had been taking action to resist the trend, battling back with collective imagination and sometimes with significant financial backing. Shrewsbury Town Council revitalised a 1970s market building to make it a thriving centre for food stalls, cafés and specialist shops. The council also bought a couple of run-down indoor shopping centres in the town, which can now be redeveloped with community interests in mind.

On a smaller scale is Treorchy in South Wales, which won a national best high street prize in 2019 thanks to its flourishing independent shops and cafés. They all worked together to organise cultural events with the help of an enterprising chamber of commerce.

Still, initiatives like these were exceptional. For the places at the other extreme, where boarded-up units were everywhere, the call to keep shops open could sound like a hopeless plea, and too late to make a difference.

Lockdown’s impact

In the first weeks of lockdown, it seemed that the pandemic would hasten the move online, by closing down most of the shops that were left – and seemingly leaving online as the only option. But as that slow, strange time went on, it became clear that something quite different was going on. Two years later, we can see that the lockdowns brought about a return to slower, more local and personal modes of shopping.

The shops still open for normal business – those that officially qualified as providers of “essential” goods – were being used in new (and yet old) ways. They became places to go for some vital variation in our daily routines.

People also began to make a point of supporting and using independent, local shops. At the same time, home deliveries were being organised by these smaller shops, often working together in groups. This was the case with Heathfield, a few miles from Thomas Turner’s village in East Sussex. And it was nothing to do with the networks set up by the supermarkets and other big chains.

In the media, shop assistants, working on checkouts or filling shelves, began to be referred to as “frontline workers”. The implication of this “promotion” was that they were doing invaluable work that was comparable to the public-spirited dedication of NHS employees.

The local high street seemed to be benefitting from renewed appreciation. It was as if the pandemic had demonstrated what shops were really for, and why we should not let them go. To say that shops – real shops – are a much needed community resource used to sound worthy and well-meaning. Now it just states the obvious.

A return to home delivery

Meanwhile, another, related revival is happening: home delivery. This is often assumed to have been an online invention, promoted by big supermarkets as the latest expansion of their networks and by big stores of all kinds. Some of the big home delivery names, such as Boohoo and Asos, have no physical shops at all.

But until the middle of the 20th century, most shops offered home delivery as a matter of course. For many food products, like milk or meat, this arrangement was the default. The butcher’s boy brought round the tray of meat, and the milkman delivered the bottles direct to your doorstep every morning.

With self-service came the end of most home delivery services, too. When bigger supermarkets were built on the edges of towns, in the 1980s and 1990s, the basket became a big trolley, and people put all the bags they came out with into the back of a car. As with all the other changes associated with “self”-service, the difference was that customers were doing this work themselves. The “service” was no longer provided by others.

The new delivery services offered by smaller, independent stores that started up during lockdown represented a return to local arrangements of the kind that were standard before the arrival of self-service. Yet orders are often now made online. In this case, then, new technology has actively contributed to the revival of an older form of shopping.

In the East Sussex village of Rushlake Green, for example, the local shop began to offer home deliveries. This was so successful that they acquired a new delivery van with their name on the side. This marked something of a return to the 1930s, when local shops first started investing in a “motor van” to make deliveries (a new trend much remarked on in the trade handbooks of the time).

As it happens, this joining of the traditional with the latest tech is itself a long established phenomenon in the history of retail distribution. New modes of transport and communication have repeatedly modified the existing conditions of shopping, and the current manifestation has striking antecedents.

Virginia Woolf’s last novel, Between the Acts, offers a nice illustration of this. It is set at the end of the 1930s, when the installation of domestic telephones was beginning to make it possible for affluent customers to ring up the shop and order their meat or groceries for delivery, without having to leave the house or send a servant.

One scene in the novel has a country lady distractedly ordering fish “in time for lunch”, while she brushes her hair in front of the mirror and murmurs lines of poetry to herself. A few pages later, just as she requested, “The fish had been delivered. Mitchell’s boy, holding them in a crook of his arm, jumped off his motor bike.”

The narrator stays with this small domestic event for a moment, commenting on how the motorbike, a recent arrival on the local scene, is driving slow old habits out of use.

No feeding the pony with lumps of sugar at the kitchen door, nor time for gossip since his round had been increased.

In Woolf’s time, this mode of transport, along with the phoned-in order, was a notable innovation, allowing just-in-time gourmet food deliveries. Almost a century later, the exclusive telephone is now the semi-universal smartphone, but the method of ordering at a distance is the same. And as it turns out, the motorbike has not been superseded in the online age of Deliveroo.

For you: more from our Insights series:

The discovery of insulin: a story of monstrous egos and toxic rivalries

How your culture informs the emotions you feel when listening to music

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Rachel Bowlby does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

depression default pandemic deaths lockdown europe ukGovernment

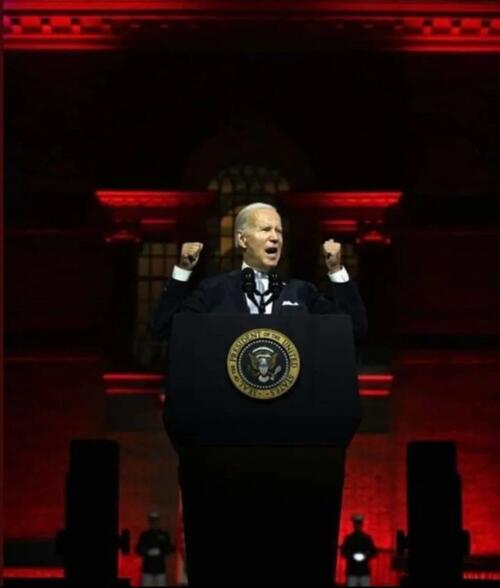

President Biden Delivers The “Darkest, Most Un-American Speech Given By A President”

President Biden Delivers The "Darkest, Most Un-American Speech Given By A President"

Having successfully raged, ranted, lied, and yelled through…

Having successfully raged, ranted, lied, and yelled through the State of The Union, President Biden can go back to his crypt now.

Whatever 'they' gave Biden, every American man, woman, and the other should be allowed to take it - though it seems the cocktail brings out 'dark Brandon'?

Tl;dw: Biden's Speech tonight ...

-

Fund Ukraine.

-

Trump is threat to democracy and America itself.

-

Abortion is good.

-

American Economy is stronger than ever.

-

Inflation wasn't Biden's fault.

-

Illegals are Americans too.

-

Republicans are responsible for the border crisis.

-

Trump is bad.

-

Biden stands with trans-children.

-

J6 was the worst insurrection since the Civil War.

(h/t @TCDMS99)

Tucker Carlson's response sums it all up perfectly:

"that was possibly the darkest, most un-American speech given by an American president. It wasn't a speech, it was a rant..."

Carlson continued: "The true measure of a nation's greatness lies within its capacity to control borders, yet Bid refuses to do it."

"In a fair election, Joe Biden cannot win"

And concluded:

“There was not a meaningful word for the entire duration about the things that actually matter to people who live here.”

Victor Davis Hanson added some excellent color, but this was probably the best line on Biden:

"he doesn't care... he lives in an alternative reality."

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) March 8, 2024

* * *

Watch SOTU Live here...

* * *

Mises' Connor O'Keeffe, warns: "Be on the Lookout for These Lies in Biden's State of the Union Address."

On Thursday evening, President Joe Biden is set to give his third State of the Union address. The political press has been buzzing with speculation over what the president will say. That speculation, however, is focused more on how Biden will perform, and which issues he will prioritize. Much of the speech is expected to be familiar.

The story Biden will tell about what he has done as president and where the country finds itself as a result will be the same dishonest story he's been telling since at least the summer.

He'll cite government statistics to say the economy is growing, unemployment is low, and inflation is down.

Something that has been frustrating Biden, his team, and his allies in the media is that the American people do not feel as economically well off as the official data says they are. Despite what the White House and establishment-friendly journalists say, the problem lies with the data, not the American people's ability to perceive their own well-being.

As I wrote back in January, the reason for the discrepancy is the lack of distinction made between private economic activity and government spending in the most frequently cited economic indicators. There is an important difference between the two:

-

Government, unlike any other entity in the economy, can simply take money and resources from others to spend on things and hire people. Whether or not the spending brings people value is irrelevant

-

It's the private sector that's responsible for producing goods and services that actually meet people's needs and wants. So, the private components of the economy have the most significant effect on people's economic well-being.

Recently, government spending and hiring has accounted for a larger than normal share of both economic activity and employment. This means the government is propping up these traditional measures, making the economy appear better than it actually is. Also, many of the jobs Biden and his allies take credit for creating will quickly go away once it becomes clear that consumers don't actually want whatever the government encouraged these companies to produce.

On top of all that, the administration is dealing with the consequences of their chosen inflation rhetoric.

Since its peak in the summer of 2022, the president's team has talked about inflation "coming back down," which can easily give the impression that it's prices that will eventually come back down.

But that's not what that phrase means. It would be more honest to say that price increases are slowing down.

Americans are finally waking up to the fact that the cost of living will not return to prepandemic levels, and they're not happy about it.

The president has made some clumsy attempts at damage control, such as a Super Bowl Sunday video attacking food companies for "shrinkflation"—selling smaller portions at the same price instead of simply raising prices.

In his speech Thursday, Biden is expected to play up his desire to crack down on the "corporate greed" he's blaming for high prices.

In the name of "bringing down costs for Americans," the administration wants to implement targeted price ceilings - something anyone who has taken even a single economics class could tell you does more harm than good. Biden would never place the blame for the dramatic price increases we've experienced during his term where it actually belongs—on all the government spending that he and President Donald Trump oversaw during the pandemic, funded by the creation of $6 trillion out of thin air - because that kind of spending is precisely what he hopes to kick back up in a second term.

If reelected, the president wants to "revive" parts of his so-called Build Back Better agenda, which he tried and failed to pass in his first year. That would bring a significant expansion of domestic spending. And Biden remains committed to the idea that Americans must be forced to continue funding the war in Ukraine. That's another topic Biden is expected to highlight in the State of the Union, likely accompanied by the lie that Ukraine spending is good for the American economy. It isn't.

It's not possible to predict all the ways President Biden will exaggerate, mislead, and outright lie in his speech on Thursday. But we can be sure of two things. The "state of the Union" is not as strong as Biden will say it is. And his policy ambitions risk making it much worse.

* * *

The American people will be tuning in on their smartphones, laptops, and televisions on Thursday evening to see if 'sloppy joe' 81-year-old President Joe Biden can coherently put together more than two sentences (even with a teleprompter) as he gives his third State of the Union in front of a divided Congress.

President Biden will speak on various topics to convince voters why he shouldn't be sent to a retirement home.

The state of our union under President Biden: three years of decline. pic.twitter.com/Da1KOIb3eR

— Speaker Mike Johnson (@SpeakerJohnson) March 7, 2024

According to CNN sources, here are some of the topics Biden will discuss tonight:

Economic issues: Biden and his team have been drafting a speech heavy on economic populism, aides said, with calls for higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy – an attempt to draw a sharp contrast with Republicans and their likely presidential nominee, Donald Trump.

Health care expenses: Biden will also push for lowering health care costs and discuss his efforts to go after drug manufacturers to lower the cost of prescription medications — all issues his advisers believe can help buoy what have been sagging economic approval ratings.

Israel's war with Hamas: Also looming large over Biden's primetime address is the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, which has consumed much of the president's time and attention over the past few months. The president's top national security advisers have been working around the clock to try to finalize a ceasefire-hostages release deal by Ramadan, the Muslim holy month that begins next week.

An argument for reelection: Aides view Thursday's speech as a critical opportunity for the president to tout his accomplishments in office and lay out his plans for another four years in the nation's top job. Even though viewership has declined over the years, the yearly speech reliably draws tens of millions of households.

Sources provided more color on Biden's SOTU address:

The speech is expected to be heavy on economic populism. The president will talk about raising taxes on corporations and the wealthy. He'll highlight efforts to cut costs for the American people, including pushing Congress to help make prescription drugs more affordable.

Biden will talk about the need to preserve democracy and freedom, a cornerstone of his re-election bid. That includes protecting and bolstering reproductive rights, an issue Democrats believe will energize voters in November. Biden is also expected to promote his unity agenda, a key feature of each of his addresses to Congress while in office.

Biden is also expected to give remarks on border security while the invasion of illegals has become one of the most heated topics among American voters. A majority of voters are frustrated with radical progressives in the White House facilitating the illegal migrant invasion.

It is probable that the president will attribute the failure of the Senate border bill to the Republicans, a claim many voters view as unfounded. This is because the White House has the option to issue an executive order to restore border security, yet opts not to do so

Maybe this is why?

Most Americans are still unaware that the census counts ALL people, including illegal immigrants, for deciding how many House seats each state gets!

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 7, 2024

This results in Dem states getting roughly 20 more House seats, which is another strong incentive for them not to deport illegals.

While Biden addresses the nation, the Biden administration will be armed with a social media team to pump propaganda to at least 100 million Americans.

"The White House hosted about 70 creators, digital publishers, and influencers across three separate events" on Wednesday and Thursday, a White House official told CNN.

Not a very capable social media team...

The State of Confusion https://t.co/C31mHc5ABJ

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) March 7, 2024

The administration's move to ramp up social media operations comes as users on X are mostly free from government censorship with Elon Musk at the helm. This infuriates Democrats, who can no longer censor their political enemies on X.

Meanwhile, Democratic lawmakers tell Axios that the president's SOTU performance will be critical as he tries to dispel voter concerns about his elderly age. The address reached as many as 27 million people in 2023.

"We are all nervous," said one House Democrat, citing concerns about the president's "ability to speak without blowing things."

The SOTU address comes as Biden's polling data is in the dumps.

BetOnline has created several money-making opportunities for gamblers tonight, such as betting on what word Biden mentions the most.

As well as...

We will update you when Tucker Carlson's live feed of SOTU is published.

Fuck it. We’ll do it live! Thursday night, March 7, our live response to Joe Biden’s State of the Union speech. pic.twitter.com/V0UwOrgKvz

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) March 6, 2024

International

What is intersectionality and why does it make feminism more effective?

The social categories that we belong to shape our understanding of the world in different ways.

The way we talk about society and the people and structures in it is constantly changing. One term you may come across this International Women’s Day is “intersectionality”. And specifically, the concept of “intersectional feminism”.

Intersectionality refers to the fact that everyone is part of multiple social categories. These include gender, social class, sexuality, (dis)ability and racialisation (when people are divided into “racial” groups often based on skin colour or features).

These categories are not independent of each other, they intersect. This looks different for every person. For example, a black woman without a disability will have a different experience of society than a white woman without a disability – or a black woman with a disability.

An intersectional approach makes social policy more inclusive and just. Its value was evident in research during the pandemic, when it became clear that women from various groups, those who worked in caring jobs and who lived in crowded circumstances were much more likely to die from COVID.

A long-fought battle

American civil rights leader and scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw first introduced the term intersectionality in a 1989 paper. She argued that focusing on a single form of oppression (such as gender or race) perpetuated discrimination against black women, who are simultaneously subjected to both racism and sexism.

Crenshaw gave a name to ways of thinking and theorising that black and Latina feminists, as well as working-class and lesbian feminists, had argued for decades. The Combahee River Collective of black lesbians was groundbreaking in this work.

They called for strategic alliances with black men to oppose racism, white women to oppose sexism and lesbians to oppose homophobia. This was an example of how an intersectional understanding of identity and social power relations can create more opportunities for action.

These ideas have, through political struggle, come to be accepted in feminist thinking and women’s studies scholarship. An increasing number of feminists now use the term “intersectional feminism”.

The term has moved from academia to feminist activist and social justice circles and beyond in recent years. Its popularity and widespread use means it is subjected to much scrutiny and debate about how and when it should be employed. For example, some argue that it should always include attention to racism and racialisation.

Recognising more issues makes feminism more effective

In writing about intersectionality, Crenshaw argued that singular approaches to social categories made black women’s oppression invisible. Many black feminists have pointed out that white feminists frequently overlook how racial categories shape different women’s experiences.

One example is hair discrimination. It is only in the 2020s that many organisations in South Africa, the UK and US have recognised that it is discriminatory to regulate black women’s hairstyles in ways that render their natural hair unacceptable.

This is an intersectional approach. White women and most black men do not face the same discrimination and pressures to straighten their hair.

“Abortion on demand” in the 1970s and 1980s in the UK and USA took no account of the fact that black women in these and many other countries needed to campaign against being given abortions against their will. The fight for reproductive justice does not look the same for all women.

Similarly, the experiences of working-class women have frequently been rendered invisible in white, middle class feminist campaigns and writings. Intersectionality means that these issues are recognised and fought for in an inclusive and more powerful way.

In the 35 years since Crenshaw coined the term, feminist scholars have analysed how women are positioned in society, for example, as black, working-class, lesbian or colonial subjects. Intersectionality reminds us that fruitful discussions about discrimination and justice must acknowledge how these different categories affect each other and their associated power relations.

This does not mean that research and policy cannot focus predominantly on one social category, such as race, gender or social class. But it does mean that we cannot, and should not, understand those categories in isolation of each other.

Ann Phoenix does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

africa uk pandemicGovernment

Biden defends immigration policy during State of the Union, blaming Republicans in Congress for refusing to act

A rising number of Americans say that immigration is the country’s biggest problem. Biden called for Congress to pass a bipartisan border and immigration…

President Joe Biden delivered the annual State of the Union address on March 7, 2024, casting a wide net on a range of major themes – the economy, abortion rights, threats to democracy, the wars in Gaza and Ukraine – that are preoccupying many Americans heading into the November presidential election.

The president also addressed massive increases in immigration at the southern border and the political battle in Congress over how to manage it. “We can fight about the border, or we can fix it. I’m ready to fix it,” Biden said.

But while Biden stressed that he wants to overcome political division and take action on immigration and the border, he cautioned that he will not “demonize immigrants,” as he said his predecessor, former President Donald Trump, does.

“I will not separate families. I will not ban people from America because of their faith,” Biden said.

Biden’s speech comes as a rising number of American voters say that immigration is the country’s biggest problem.

Immigration law scholar Jean Lantz Reisz answers four questions about why immigration has become a top issue for Americans, and the limits of presidential power when it comes to immigration and border security.

1. What is driving all of the attention and concern immigration is receiving?

The unprecedented number of undocumented migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border right now has drawn national concern to the U.S. immigration system and the president’s enforcement policies at the border.

Border security has always been part of the immigration debate about how to stop unlawful immigration.

But in this election, the immigration debate is also fueled by images of large groups of migrants crossing a river and crawling through barbed wire fences. There is also news of standoffs between Texas law enforcement and U.S. Border Patrol agents and cities like New York and Chicago struggling to handle the influx of arriving migrants.

Republicans blame Biden for not taking action on what they say is an “invasion” at the U.S. border. Democrats blame Republicans for refusing to pass laws that would give the president the power to stop the flow of migration at the border.

2. Are Biden’s immigration policies effective?

Confusion about immigration laws may be the reason people believe that Biden is not implementing effective policies at the border.

The U.S. passed a law in 1952 that gives any person arriving at the border or inside the U.S. the right to apply for asylum and the right to legally stay in the country, even if that person crossed the border illegally. That law has not changed.

Courts struck down many of former President Donald Trump’s policies that tried to limit immigration. Trump was able to lawfully deport migrants at the border without processing their asylum claims during the COVID-19 pandemic under a public health law called Title 42. Biden continued that policy until the legal justification for Title 42 – meaning the public health emergency – ended in 2023.

Republicans falsely attribute the surge in undocumented migration to the U.S. over the past three years to something they call Biden’s “open border” policy. There is no such policy.

Multiple factors are driving increased migration to the U.S.

More people are leaving dangerous or difficult situations in their countries, and some people have waited to migrate until after the COVID-19 pandemic ended. People who smuggle migrants are also spreading misinformation to migrants about the ability to enter and stay in the U.S.

3. How much power does the president have over immigration?

The president’s power regarding immigration is limited to enforcing existing immigration laws. But the president has broad authority over how to enforce those laws.

For example, the president can place every single immigrant unlawfully present in the U.S. in deportation proceedings. Because there is not enough money or employees at federal agencies and courts to accomplish that, the president will usually choose to prioritize the deportation of certain immigrants, like those who have committed serious and violent crimes in the U.S.

The federal agency Immigration and Customs Enforcement deported more than 142,000 immigrants from October 2022 through September 2023, double the number of people it deported the previous fiscal year.

But under current law, the president does not have the power to summarily expel migrants who say they are afraid of returning to their country. The law requires the president to process their claims for asylum.

Biden’s ability to enforce immigration law also depends on a budget approved by Congress. Without congressional approval, the president cannot spend money to build a wall, increase immigration detention facilities’ capacity or send more Border Patrol agents to process undocumented migrants entering the country.

4. How could Biden address the current immigration problems in this country?

In early 2024, Republicans in the Senate refused to pass a bill – developed by a bipartisan team of legislators – that would have made it harder to get asylum and given Biden the power to stop taking asylum applications when migrant crossings reached a certain number.

During his speech, Biden called this bill the “toughest set of border security reforms we’ve ever seen in this country.”

That bill would have also provided more federal money to help immigration agencies and courts quickly review more asylum claims and expedite the asylum process, which remains backlogged with millions of cases, Biden said. Biden said the bipartisan deal would also hire 1,500 more border security agents and officers, as well as 4,300 more asylum officers.

Removing this backlog in immigration courts could mean that some undocumented migrants, who now might wait six to eight years for an asylum hearing, would instead only wait six weeks, Biden said. That means it would be “highly unlikely” migrants would pay a large amount to be smuggled into the country, only to be “kicked out quickly,” Biden said.

“My Republican friends, you owe it to the American people to get this bill done. We need to act,” Biden said.

Biden’s remarks calling for Congress to pass the bill drew jeers from some in the audience. Biden quickly responded, saying that it was a bipartisan effort: “What are you against?” he asked.

Biden is now considering using section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act to get more control over immigration. This sweeping law allows the president to temporarily suspend or restrict the entry of all foreigners if their arrival is detrimental to the U.S.

This obscure law gained attention when Trump used it in January 2017 to implement a travel ban on foreigners from mainly Muslim countries. The Supreme Court upheld the travel ban in 2018.

Trump again also signed an executive order in April 2020 that blocked foreigners who were seeking lawful permanent residency from entering the country for 60 days, citing this same section of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Biden did not mention any possible use of section 212(f) during his State of the Union speech. If the president uses this, it would likely be challenged in court. It is not clear that 212(f) would apply to people already in the U.S., and it conflicts with existing asylum law that gives people within the U.S. the right to seek asylum.

Jean Lantz Reisz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

congress senate trump pandemic covid-19 mexico ukraine-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

Government1 month ago

Government1 month agoWar Delirium

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges