How much does climate change* actually affect GDP? How much will currently-envisioned climate policies reduce that damage, and thereby raise GDP? As we prepare to spend trillions and trillions of dollars on climate change, this certainly seems like the important question that economists should have good answers for. I'm looking in to what anyone actually knows about these questions. The answer is surprisingly little, and it seems a ripe area for research. This post begins a series.

I haven't gotten deep in this issue before, because of a set of overriding facts and logical problems. I don't see how these will change, but the question frames my investigation.

An illogical question

The economic effects of climate change are dwarfed by growth.

Take even worst-case estimates that climate change will lower GDP by 5-10% in the year 2100. Compared to growth, that's couch change. At our current tragically low 2% per year, without even compounding (or in logs), GDP in 2100 will be 160% greater than now. Climate change will make 2100 be as terrible as... 2095 would otherwise be. If we could boost growth to 3% per year, GDP in 2100 will be 240% greater than now, an extra 80 percentage points. 8% in 80 years is one tenth of a percent per year growth. That's tiny.

In the 72 years since 1947, US GDP per capita grew from $14,000 to $57,000 in real terms, a 400% increase, and real GDP itself grew from $2,027 T to $19,086 T, a 900% increase. Just returning to the 1945-2000 growth rate would dwarf the effects of climate change and the GDP-increasing effects of climate policy.

Comparing the US and Europe, Europe is about 40% below the US in GDP Per Capita, and the the US is about 60% above Europe. So Europe's institutions do on the order of 5-10 times more damage to GDP than climate change.

Residential zoning alone costs something like 10-20% of GDP, by keeping people away from high productivity jobs. Abandoning migration restrictions could as much as double world GDP (also here).

It is often said that climate change will hit different countries differentially, and poor countries more, so it's an "equity" issue as much as a rich-country GDP issue. Yet just since 1990, China's GDP Per Capita has grown 1,100%, from $729 to $8405 (World bank). As the world got hotter. 1,100% is a lot more than 10%. We'll look at poor country GDP climate effects, but from what I've seen so far, reducing carbon doesn't get 1,100% gains.

India's GDP Per Capita is $2,000. The US at $60,000 is 30 times greater, or 2,900% more. Adopting US institutions could raise India's GDP by 2,900% in a century, and that's the cost of not doing so. And US institutions are far from perfect. That's a lot more than 10%

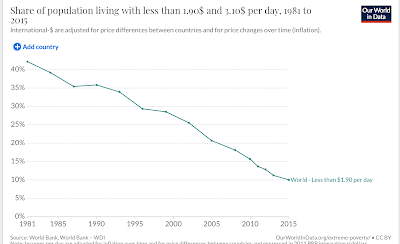

The share of the world population in extreme poverty is plummeting. No plausible estimate of climate damage comes close to this kind of change. And this change comes in part from increasing diffusion of fossil fuels. People who used to hoe by hand now use tractors.

Logically, then, if the question is "how do we increase GDP or GDP Per Capita by 10% in 2010" the answer is, "get out of the way of economic growth and do everything possible to speed it up." And you'll get a lot more than 10% out of that. If the question is, "how do we reduce global poverty" the answer is, "get out of the way of economic growth and do everything possible to speed it up."

I suppose it would make sense to focus on climate if economic growth were going as fast as possible, all government policies were perfect, and climate policy were the last lever in hand to raise GDP 10% by 2010. But that's ludicrous. Economic growth is not going as fast as possible. Most government policy is devoted to slowing down economic growth, in order to change the distribution of income, and mostly not to flatten the distribution of income especially internationally. If we want to spend a few trillion now to increase GDP in 2100, windmills and electric cars are, even at inflated estimates about the least efficient ways to do so. It's almost as ludicrous as California's governors' intimations that the way to solve the water and wildfire problems is to build a high speed train.

"Once you start thinking about growth, it's hard to think about anything else," says Bob Lucas. He's right about economists, but wrong about everyone else. People, politicians, bureaucrats, lobbyists, media, activists, and governments seem devoted to thinking about just about anything but economic growth. Growth comes from innovation and displacement of old companies and industries and entrenched elites with new ones and everybody with any political power hates it. See Uber vs. Taxi companies.

A logical conundrum

We have fallen victims to an amazing lapse of basic logic. We ask "what is the economic effect of climate change?" We then discount damages assess costs, and discuss cost benefit analysis of carbon policies.

(Well, "we" economists do. Public policy on this issue has left cost-benefit analysis in the rear-view mirror. Defunding fossil fuels, canceling Keystone but not Nord 3, building electric-car charging stations across North Dakota..is anyone doing any cost-benefit analysis? How much cost today vs. benefit in 2100 GDP is calculated to justify central bank's new climate dirigisme? But I digress. Let's pretend that cost today vs. benefit in 2100 will have some influence on policy.)

The logic is, climate change will (maybe) hurt the economy in 2100. By spending money, or suffering loss of income to do things in more costly but less carbon-intensive ways now, we can raise GDP in 2100. So, depending on the economic damage of carbon later, the cost of cleaning it up now, and the discount rate, we should do it. We should embark on carbon policy because it raises GDP in 2100. That is the inescapable logic of the economic approach.

But reducing carbon is thus, logically, just one item on the list of answers to "What can we do to raise GDP in 2100?," and especially "What can we do to raise GDP in currently-poor countries by 2100?" Asked that way, you can see that "lower carbon emissions" is about #100 on the list, even admitting the 5-10% of GDP thumb-on-the-scale estimates. It's like asking whether removing that "Go Bears" flag from your radio antenna will improve your gas mileage and lower your overall expenses. Well, yes, maybe, but it's hardly first on the list.

There must be some behavioral name for the bias that focuses on a tiny insignificant little cause and effect, leaving much more important questions languishing. Whatever it is, that's where we are.

Moreover, viewed this way it's not even obvious that climate policy should do anything. To my uncomfortable truth that Europe lags 40% of GDP per capita behind the US, Europeans may say, well we're happy with that tradeoff; our welfare state and long vacations are worth it. The US political system has made the tradeoff that 10-20% of GDP is worth whatever the benefits of residential zoning are, and the whole word bars immigration. Fossil fuels have real benefits, especially to the world's poor. Cooking with propane rather than "renewable" cow chips has immense health benefits. Now. Waiting for solar cells + batteries + electric for cooking, air conditioning, basic transport, is a large cost. Maybe 10% of GDP in 2100 is worth it in the same way that we tolerate these far larger GDP costs now.

If not "this is the best most cost-effective way to raise global GDP in the year 2100?" -- which it surely is not -- then what is the question to which current climate policy is the answer?

Catastrophes?

Even if you are not a climate activist, you surely are frothing at the mouth with objections. Well, we don't want to stop climate change just because it's the most cost-efficient way to raise world GDP in 2100, I'm sure you're saying. Filthy lucre is not the only reason to stop the "climate emergency."

OK, but why not? If not for a more prosperous future, why are we embarking on trillions of cost, many more trillions of foregone growth, especially in developing countries?

Many arguments are raised. Maybe 5-10% is wrong, and we are on the edge of a "tipping point," a complete breakdown in which global GDP crashes. Indeed, 5-10% of GDP in 80 years hardly qualifies as an "emergency." Maybe a tipping point does? But that is nowhere in any science I have seen so far, though I will be looking for it. Is there a vaguely reasonable scenario in which GDP not just grows one tenth of a percent per year more slowly, but actually collapses?

If so, then the 5-10% by 2010 calculations are completely irrelevant -- only the chance of this collapse matters. We should, and I will, look for concrete climate and economic scenarios that lead to collapse.

But the same logical problem arises with catastrophism. Suppose the answer is, we need to enact costly climate policy because we need to avert the small chance of a civilization-ending catastrophe in 100 years. Then I get to ask, Is a slow-moving, very predictable change in climate, in a race with adaptation and technology, really the greatest threat to civilization, and the one where 10 trillion dollars now has the greatest effect? What about nuclear war, civil war, pandemic, crop failure, antibiotic resistant bacteria, asteroid strike, and most of all the general decline and fall we see all around us?

There is an argument that says, well, nobody knows but it could happen. So take out some insurance. But if we spend $10 trillion dollars on every possible unknown poorly understood low-probability event, we won't have anything left. You have to quantify damage, probability, and the cost-benefit channel.

As we did not start with a list of ways to improve GDP in 80 years and, look, climate policy is the most cost-effective, so we did not start with a list of ways to avoid civilizational collapse and, look, climate policy is the most cost-effective.

Environment?

Maybe it's not about GDP at all. Something about natural stewardship, keeping the world as we found it, and so forth clearly motivates climate policy.

I'm pretty much of an environmentalist too, it may surprise you to learn. The environment and natural world are worth preserving and restoring, even at substantial cost. We are living through a mass extinction, larger than the dinosaurs, though it started about 13,000 years ago not just when fossil fuels came along. Much of humanity lives with unsafe air and water, full of things much more directly damaging to health right now than carbon dioxide.

But the same logical conundrum applies.

Yes, climate change is not good for many endangered species. But elephants and rhinos will be dead from people shooting them and taking over habitat long before it gets too hot for them, just as thousands of megafauna species before them. A trillion dollars would buy one heck of a wilderness area. If the question is, "what's the most damaging human activity to species and the most cost-effective way to preserve species -- and especially not-so-photogenic but really biologically important species?" climate change goes back to #100 on the list. If the question is "what are the greatest environmental dangers to human health, and the most cost effective steps to improving the human environment?" climate change goes back to #100 on the list.

Moreover, if this is the question, then it's a mistake for advocates to even talk about GDP. We're going to lower GDP in the year 2100, deliberately, to help the environment. But we're talking about huge amounts of money -- tens of trillions at least of direct expenditure and more of foregone growth. We have to put some dollar figures to the benefits and the costs.

An answer in search of a question

It's really not about GDP is it? Suppose when we end this investigation, we find that there are no economic costs at all to climate change. Sure, the planet gets several degrees warmer, ice sheets melt, seas rise, costs of adaptation must be borne, but when you add it all up the overall effect on GDP is zero. Or (gasp) suppose warming is actually beneficial to GDP. Would that end the urgent desire of those who want to do climate policy to do so? I don't think it would have much effect at all. Already pro-climate arguments mistake costs and benefits with three and four zeros in the wrong place.

Climate policy at the current moment seems like an answer in search of a question. If we had noticed carbon, as we did freon, and set in motion a small research and development effort leading to a mildly costly transition -- say a few hundred billion a year, couch change for today's governments -- that would be a different matter. But with a "whole-of-government" whole of society project, with tens of trillions of costs involved, just what the question is starts to matter.

This is like a husband who really wants to buy a new truck. "Honey, " he says, "we could use the truck to go get some new pavers for the yard at Home Depot." "They deliver," she answers. "We could take the bikes up to the mountains for a nice trip," he adds. "We could also buy a bike rack for the car," she answers. Yes, the truck would have a lot of nice benefits. But in each case, "what's the right way to answer this problem" is not to buy a truck.

So we are with current climate policy. The current climate policy package -- shut down advanced-country fossil fuels (Keystone no, Nord stream yes, promises from China), subsidies to windmills, solar, electric cars; no nuclear, geoengineering, carbon capture, or heavy R&D to hydrogen, geothermal fracking etc. -- really does not have a question. Even if the costs of climate are 5-10% of GDP in 2100, the marginal improvement of these very expensive policies will not change that much. (Coming soon). If we find that climate has no effect on GDP, or if we find that there are far better ways to improve the lot of the world's poor and disadvantaged, that will not silence climate policy advocates. If we find that climate has no effect on species or human health, or that there are far better ways to advance these goals, that will not silence climate policy advocates.

What is the question? I'm not sure. Stating one to which this policy set is the logical answer would surely help.

Well, let's get back to the question that economists can answer -- what are the effects of climate change on the economy? Stay tuned...

*A note on language

Global warming climate change climate crisis climate justice climate emergency.

I will stick with last year's PC terminology "climate change." In the beginning there was "global warming," the rather uncontroversial statement that carbon dioxide emissions were warming the planet. This did not spur enough action, so it moved to "climate change." In part that reflects the reality that some places will be hit more than others, that some places benefit from hotter temperatures, and the much less scientifically established claim that there will be more extreme weather -- fires, droughts, hurricanes etc. That too was apparently not enough, so there was a brief foray to "climate justice," entwining climate change with all sorts of "social justice" issues that really have nothing to do with it. "Climate crisis" seemed good enough for a while, but even that has not scared enough people into supporting the current policy package. "Climate emergency" we are now to call it, or so baptizes the (now profoundly un-) Scientific American. Will "climate catastrophe" be next? Fast-evolving, virtue-signaling, political-affiliation labeling, increasingly hysterical language, and conscious efforts to choose language to push policy goals, are also not a good sign of clear scientific thinking. The "truck emergency" didn't work either.

subsidies

economic growth

pandemic

gdp

india

europe

china

Read More