International

How banks are trying to capture the green transition

How banks are trying to capture the green transition

Private sector banks in the UK should have a central role in financing climate action and supporting a just transition to a low carbon economy. That’s according to a new report from the Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics.

Framed as a strategic opportunity that climate change represents for investors, the report identifies four specific reasons why banks should support the just transition. It would reinforce trust after the financial crisis; it would demonstrate leadership; it would reduce their exposure to material climate risks; and it would expand their customer base by creating demand for new services and products.

The report is not alone in its attempt to put banking and finance at the centre of a green and just transition. Similar arguments are presented by the World Bank, by the European Union, and by many national task forces on financing the transition, including the UK’s.

In all these cases, banks and financial markets are presented as essential allies in the green and just transition. At the same time, the climate emergency is described as a chance that finance cannot miss. Not because of the legal duties that arise from international conventions and the national framework, but because banking the green transition could help reestablish public legitimacy, innovate and guarantee future cashflow.

Twelve years after the financial crisis, we may be aware that banks and finance were responsible for the intensification of climate change and the exacerbation of inequality, but such reports say our future is still inexorably in their hands.

Is there no alternative to climate finance?

Four decades on from British prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s infamous motto that There Is No Alternative to the rule of the market, the relationship between financial capital and the green and just transition is presented as universal and inevitable. However, a vision of the future is a political construction whose strength and content depend on who is shaping it, the depth of their networks and their capacity transform a vision into reality.

In the case of climate finance, it seems that a very limited number of people and institutions have been strategically occupying key spaces in the public debate and contributed to the reproduction of this monotone vision. In our ongoing research we are mapping various groups involved in green financial policymaking: the EU’s High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance and its Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance, the UK Green Finance Task Force, the participants to the 2018 and 2019 Green Finance Summits in London and the authors behind publications like the LSE’s Banking on a Just Transition report.

Across these networks, key positions are occupied by current and former private industry leaders. Having done well out of the status quo, their trajectories and profiles denote a clear orientation in favour of deregulation and a strong private sector.

Often, the same people and organisations operate across networks and influence both regional and national conversations. Others are hubs that occupy a pivotal role in the construction of the network and in the predisposition of the spaces and guidelines for dialogue and policy making. This is the case, for example, of the Climate Bond Initiative (CBI), a relatively young international NGO headquartered in London whose sole mission is to “mobilise the largest capital market of all, the [US]$100 trillion bond market, for climate change solutions”. Characterised by a strong pro-private finance attitude, CBI proposes policy actions that are infused by the inevitability of aligning the interests of the finance industry with those of the planet.

Let’s unbank the green and just transition

COVID-19 has emphasised the socio-economic fragility of global financial capitalism and represents the shock that may lead to an acceleration of political processes. While corporate giants are declaring bankruptcy and millions are losing their jobs, governments in Europe and across the global north continue to pump trillions into rescuing and relaunching the economy in the name of the green recovery.

Political debate and positioning will decide whether these public funds will be spent on bailouts or public investments, on tax breaks for the 1% or provision of essential services, or whether the focus will be on green growth or climate justice. But private finance is already capturing this debate and may become a key beneficiary. Getting a green and just transition does not only depend on the voices that are heard, but also those that are silenced.

Intellectual and political elites on the side of the banks are making it harder to have a serious discussion about addressing climate change. NGOs and campaign groups are participating, but only if they share the premises and objectives of the financial sector.

This crowds out more transformative voices from civil society and the academy, and establishes a false public narrative of agreed actions despite the numerous voices outside of this club. And it also normalises the priority of financial market activities, putting profit before people and planet.

The current crisis is an opportunity to rethink what a green and just transition would entail. We must continue to question the role of finance rather than taking it for granted and ensure that the “green and just transition” becomes precisely that: green and just, rather than another source of profits for banks and the 1%.

Tomaso Ferrando received funding from the British Academy Newton Fund and the Flanders Research Foundation (FWO) to research the establishment and expansion of the market for green bonds.

Daniel Tischer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Spread & Containment

Four Years Ago This Week, Freedom Was Torched

Four Years Ago This Week, Freedom Was Torched

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Brownstone Institute,

"Beware the Ides of March,” Shakespeare…

Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Brownstone Institute,

"Beware the Ides of March,” Shakespeare quotes the soothsayer’s warning Julius Caesar about what turned out to be an impending assassination on March 15. The death of American liberty happened around the same time four years ago, when the orders went out from all levels of government to close all indoor and outdoor venues where people gather.

It was not quite a law and it was never voted on by anyone. Seemingly out of nowhere, people who the public had largely ignored, the public health bureaucrats, all united to tell the executives in charge – mayors, governors, and the president – that the only way to deal with a respiratory virus was to scrap freedom and the Bill of Rights.

And they did, not only in the US but all over the world.

The forced closures in the US began on March 6 when the mayor of Austin, Texas, announced the shutdown of the technology and arts festival South by Southwest. Hundreds of thousands of contracts, of attendees and vendors, were instantly scrapped. The mayor said he was acting on the advice of his health experts and they in turn pointed to the CDC, which in turn pointed to the World Health Organization, which in turn pointed to member states and so on.

There was no record of Covid in Austin, Texas, that day but they were sure they were doing their part to stop the spread. It was the first deployment of the “Zero Covid” strategy that became, for a time, official US policy, just as in China.

It was never clear precisely who to blame or who would take responsibility, legal or otherwise.

This Friday evening press conference in Austin was just the beginning. By the next Thursday evening, the lockdown mania reached a full crescendo. Donald Trump went on nationwide television to announce that everything was under control but that he was stopping all travel in and out of US borders, from Europe, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. American citizens would need to return by Monday or be stuck.

Americans abroad panicked while spending on tickets home and crowded into international airports with waits up to 8 hours standing shoulder to shoulder. It was the first clear sign: there would be no consistency in the deployment of these edicts.

There is no historical record of any American president ever issuing global travel restrictions like this without a declaration of war. Until then, and since the age of travel began, every American had taken it for granted that he could buy a ticket and board a plane. That was no longer possible. Very quickly it became even difficult to travel state to state, as most states eventually implemented a two-week quarantine rule.

The next day, Friday March 13, Broadway closed and New York City began to empty out as any residents who could went to summer homes or out of state.

On that day, the Trump administration declared the national emergency by invoking the Stafford Act which triggers new powers and resources to the Federal Emergency Management Administration.

In addition, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a classified document, only to be released to the public months later. The document initiated the lockdowns. It still does not exist on any government website.

The White House Coronavirus Response Task Force, led by the Vice President, will coordinate a whole-of-government approach, including governors, state and local officials, and members of Congress, to develop the best options for the safety, well-being, and health of the American people. HHS is the LFA [Lead Federal Agency] for coordinating the federal response to COVID-19.

Closures were guaranteed:

Recommend significantly limiting public gatherings and cancellation of almost all sporting events, performances, and public and private meetings that cannot be convened by phone. Consider school closures. Issue widespread ‘stay at home’ directives for public and private organizations, with nearly 100% telework for some, although critical public services and infrastructure may need to retain skeleton crews. Law enforcement could shift to focus more on crime prevention, as routine monitoring of storefronts could be important.

In this vision of turnkey totalitarian control of society, the vaccine was pre-approved: “Partner with pharmaceutical industry to produce anti-virals and vaccine.”

The National Security Council was put in charge of policy making. The CDC was just the marketing operation. That’s why it felt like martial law. Without using those words, that’s what was being declared. It even urged information management, with censorship strongly implied.

The timing here is fascinating. This document came out on a Friday. But according to every autobiographical account – from Mike Pence and Scott Gottlieb to Deborah Birx and Jared Kushner – the gathered team did not meet with Trump himself until the weekend of the 14th and 15th, Saturday and Sunday.

According to their account, this was his first real encounter with the urge that he lock down the whole country. He reluctantly agreed to 15 days to flatten the curve. He announced this on Monday the 16th with the famous line: “All public and private venues where people gather should be closed.”

This makes no sense. The decision had already been made and all enabling documents were already in circulation.

There are only two possibilities.

One: the Department of Homeland Security issued this March 13 HHS document without Trump’s knowledge or authority. That seems unlikely.

Two: Kushner, Birx, Pence, and Gottlieb are lying. They decided on a story and they are sticking to it.

Trump himself has never explained the timeline or precisely when he decided to greenlight the lockdowns. To this day, he avoids the issue beyond his constant claim that he doesn’t get enough credit for his handling of the pandemic.

With Nixon, the famous question was always what did he know and when did he know it? When it comes to Trump and insofar as concerns Covid lockdowns – unlike the fake allegations of collusion with Russia – we have no investigations. To this day, no one in the corporate media seems even slightly interested in why, how, or when human rights got abolished by bureaucratic edict.

As part of the lockdowns, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which was and is part of the Department of Homeland Security, as set up in 2018, broke the entire American labor force into essential and nonessential.

They also set up and enforced censorship protocols, which is why it seemed like so few objected. In addition, CISA was tasked with overseeing mail-in ballots.

Only 8 days into the 15, Trump announced that he wanted to open the country by Easter, which was on April 12. His announcement on March 24 was treated as outrageous and irresponsible by the national press but keep in mind: Easter would already take us beyond the initial two-week lockdown. What seemed to be an opening was an extension of closing.

This announcement by Trump encouraged Birx and Fauci to ask for an additional 30 days of lockdown, which Trump granted. Even on April 23, Trump told Georgia and Florida, which had made noises about reopening, that “It’s too soon.” He publicly fought with the governor of Georgia, who was first to open his state.

Before the 15 days was over, Congress passed and the president signed the 880-page CARES Act, which authorized the distribution of $2 trillion to states, businesses, and individuals, thus guaranteeing that lockdowns would continue for the duration.

There was never a stated exit plan beyond Birx’s public statements that she wanted zero cases of Covid in the country. That was never going to happen. It is very likely that the virus had already been circulating in the US and Canada from October 2019. A famous seroprevalence study by Jay Bhattacharya came out in May 2020 discerning that infections and immunity were already widespread in the California county they examined.

What that implied was two crucial points: there was zero hope for the Zero Covid mission and this pandemic would end as they all did, through endemicity via exposure, not from a vaccine as such. That was certainly not the message that was being broadcast from Washington. The growing sense at the time was that we all had to sit tight and just wait for the inoculation on which pharmaceutical companies were working.

By summer 2020, you recall what happened. A restless generation of kids fed up with this stay-at-home nonsense seized on the opportunity to protest racial injustice in the killing of George Floyd. Public health officials approved of these gatherings – unlike protests against lockdowns – on grounds that racism was a virus even more serious than Covid. Some of these protests got out of hand and became violent and destructive.

Meanwhile, substance abuse rage – the liquor and weed stores never closed – and immune systems were being degraded by lack of normal exposure, exactly as the Bakersfield doctors had predicted. Millions of small businesses had closed. The learning losses from school closures were mounting, as it turned out that Zoom school was near worthless.

It was about this time that Trump seemed to figure out – thanks to the wise council of Dr. Scott Atlas – that he had been played and started urging states to reopen. But it was strange: he seemed to be less in the position of being a president in charge and more of a public pundit, Tweeting out his wishes until his account was banned. He was unable to put the worms back in the can that he had approved opening.

By that time, and by all accounts, Trump was convinced that the whole effort was a mistake, that he had been trolled into wrecking the country he promised to make great. It was too late. Mail-in ballots had been widely approved, the country was in shambles, the media and public health bureaucrats were ruling the airwaves, and his final months of the campaign failed even to come to grips with the reality on the ground.

At the time, many people had predicted that once Biden took office and the vaccine was released, Covid would be declared to have been beaten. But that didn’t happen and mainly for one reason: resistance to the vaccine was more intense than anyone had predicted. The Biden administration attempted to impose mandates on the entire US workforce. Thanks to a Supreme Court ruling, that effort was thwarted but not before HR departments around the country had already implemented them.

As the months rolled on – and four major cities closed all public accommodations to the unvaccinated, who were being demonized for prolonging the pandemic – it became clear that the vaccine could not and would not stop infection or transmission, which means that this shot could not be classified as a public health benefit. Even as a private benefit, the evidence was mixed. Any protection it provided was short-lived and reports of vaccine injury began to mount. Even now, we cannot gain full clarity on the scale of the problem because essential data and documentation remains classified.

After four years, we find ourselves in a strange position. We still do not know precisely what unfolded in mid-March 2020: who made what decisions, when, and why. There has been no serious attempt at any high level to provide a clear accounting much less assign blame.

Not even Tucker Carlson, who reportedly played a crucial role in getting Trump to panic over the virus, will tell us the source of his own information or what his source told him. There have been a series of valuable hearings in the House and Senate but they have received little to no press attention, and none have focus on the lockdown orders themselves.

The prevailing attitude in public life is just to forget the whole thing. And yet we live now in a country very different from the one we inhabited five years ago. Our media is captured. Social media is widely censored in violation of the First Amendment, a problem being taken up by the Supreme Court this month with no certainty of the outcome. The administrative state that seized control has not given up power. Crime has been normalized. Art and music institutions are on the rocks. Public trust in all official institutions is at rock bottom. We don’t even know if we can trust the elections anymore.

In the early days of lockdown, Henry Kissinger warned that if the mitigation plan does not go well, the world will find itself set “on fire.” He died in 2023. Meanwhile, the world is indeed on fire. The essential struggle in every country on earth today concerns the battle between the authority and power of permanent administration apparatus of the state – the very one that took total control in lockdowns – and the enlightenment ideal of a government that is responsible to the will of the people and the moral demand for freedom and rights.

How this struggle turns out is the essential story of our times.

CODA: I’m embedding a copy of PanCAP Adapted, as annotated by Debbie Lerman. You might need to download the whole thing to see the annotations. If you can help with research, please do.

* * *

Jeffrey Tucker is the author of the excellent new book 'Life After Lock-Down'

International

Red Candle In The Wind

Red Candle In The Wind

By Benjamin PIcton of Rabobank

February non-farm payrolls superficially exceeded market expectations on Friday by…

By Benjamin PIcton of Rabobank

February non-farm payrolls superficially exceeded market expectations on Friday by printing at 275,000 against a consensus call of 200,000. We say superficially, because the downward revisions to prior months totalled 167,000 for December and January, taking the total change in employed persons well below the implied forecast, and helping the unemployment rate to pop two-ticks to 3.9%. The U6 underemployment rate also rose from 7.2% to 7.3%, while average hourly earnings growth fell to 0.2% m-o-m and average weekly hours worked languished at 34.3, equalling pre-pandemic lows.

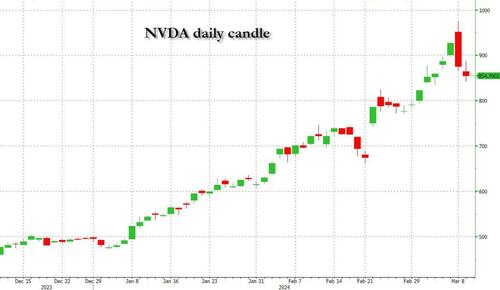

Undeterred by the devil in the detail, the algos sprang into action once exchanges opened. Market darling NVIDIA hit a new intraday high of $974 before (presumably) the humans took over and sold the stock down more than 10% to close at $875.28. If our suspicions are correct that it was the AIs buying before the humans started selling (no doubt triggering trailing stops on the way down), the irony is not lost on us.

The 1-day chart for NVIDIA now makes for interesting viewing, because the red candle posted on Friday presents quite a strong bearish engulfing signal. Volume traded on the day was almost double the 15-day simple moving average, and similar price action is observable on the 1-day charts for both Intel and AMD. Regular readers will be aware that we have expressed incredulity in the past about the durability the AI thematic melt-up, so it will be interesting to see whether Friday’s sell off is just a profit-taking blip, or a genuine trend reversal.

AI equities aside, this week ought to be important for markets because the BTFP program expires today. That means that the Fed will no longer be loaning cash to the banking system in exchange for collateral pledged at-par. The KBW Regional Banking index has so far taken this in its stride and is trading 30% above the lows established during the mini banking crisis of this time last year, but the Fed’s liquidity facility was effectively an exercise in can-kicking that makes regional banks a sector of the market worth paying attention to in the weeks ahead. Even here in Sydney, regulators are warning of external risks posed to the banking sector from scheduled refinancing of commercial real estate loans following sharp falls in valuations.

Markets are sending signals in other sectors, too. Gold closed at a new record-high of $2178/oz on Friday after trading above $2200/oz briefly. Gold has been going ballistic since the Friday before last, posting gains even on days where 2-year Treasury yields have risen. Gold bugs are buying as real yields fall from the October highs and inflation breakevens creep higher. This is particularly interesting as gold ETFs have been recording net outflows; suggesting that price gains aren’t being driven by a retail pile-in. Are gold buyers now betting on a stagflationary outcome where the Fed cuts without inflation being anchored at the 2% target? The price action around the US CPI release tomorrow ought to be illuminating.

Leaving the day-to-day movements to one side, we are also seeing further signs of structural change at the macro level. The UK budget last week included a provision for the creation of a British ISA. That is, an Individual Savings Account that provides tax breaks to savers who invest their money in the stock of British companies. This follows moves last year to encourage pension funds to head up the risk curve by allocating 5% of their capital to unlisted investments.

As a Hail Mary option for a government cruising toward an electoral drubbing it’s a curious choice, but it’s worth highlighting as cash-strapped governments increasingly see private savings pools as a funding solution for their spending priorities.

Of course, the UK is not alone in making creeping moves towards financial repression. In contrast to announcements today of increased trade liberalisation, Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmers has in the recent past flagged his interest in tapping private pension savings to fund state spending priorities, including defence, public housing and renewable energy projects. Both the UK and Australia appear intent on finding ways to open up the lungs of their economies, but government wants more say in directing private capital flows for state goals.

So, how far is the blurring of the lines between free markets and state planning likely to go? Given the immense and varied budgetary (and security) pressures that governments are facing, could we see a re-up of WWII-era Victory bonds, where private investors are encouraged to do their patriotic duty by directly financing government at negative real rates?

That would really light a fire under the gold market.

Spread & Containment

Trump “Clearly Hasn’t Learned From His COVID-Era Mistakes”, RFK Jr. Says

Trump "Clearly Hasn’t Learned From His COVID-Era Mistakes", RFK Jr. Says

Authored by Jeff Louderback via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

President…

Authored by Jeff Louderback via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

President Joe Biden claimed that COVID vaccines are now helping cancer patients during his State of the Union address on March 7, but it was a response on Truth Social from former President Donald Trump that drew the ire of independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

During the address, President Biden said: “The pandemic no longer controls our lives. The vaccines that saved us from COVID are now being used to help beat cancer, turning setback into comeback. That’s what America does.”

President Trump wrote: “The Pandemic no longer controls our lives. The VACCINES that saved us from COVID are now being used to help beat cancer—turning setback into comeback. YOU’RE WELCOME JOE. NINE-MONTH APPROVAL TIME VS. 12 YEARS THAT IT WOULD HAVE TAKEN YOU.”

An outspoken critic of President Trump’s COVID response, and the Operation Warp Speed program that escalated the availability of COVID vaccines, Mr. Kennedy said on X, formerly known as Twitter, that “Donald Trump clearly hasn’t learned from his COVID-era mistakes.”

“He fails to recognize how ineffective his warp speed vaccine is as the ninth shot is being recommended to seniors. Even more troubling is the documented harm being caused by the shot to so many innocent children and adults who are suffering myocarditis, pericarditis, and brain inflammation,” Mr. Kennedy remarked.

“This has been confirmed by a CDC-funded study of 99 million people. Instead of bragging about its speedy approval, we should be honestly and transparently debating the abundant evidence that this vaccine may have caused more harm than good.

“I look forward to debating both Trump and Biden on Sept. 16 in San Marcos, Texas.”

Mr. Kennedy announced in April 2023 that he would challenge President Biden for the 2024 Democratic Party presidential nomination before declaring his run as an independent last October, claiming that the Democrat National Committee was “rigging the primary.”

Since the early stages of his campaign, Mr. Kennedy has generated more support than pundits expected from conservatives, moderates, and independents resulting in speculation that he could take votes away from President Trump.

Many Republicans continue to seek a reckoning over the government-imposed pandemic lockdowns and vaccine mandates.

President Trump’s defense of Operation Warp Speed, the program he rolled out in May 2020 to spur the development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines amid the pandemic, remains a sticking point for some of his supporters.

Operation Warp Speed featured a partnership between the government, the military, and the private sector, with the government paying for millions of vaccine doses to be produced.

President Trump released a statement in March 2021 saying: “I hope everyone remembers when they’re getting the COVID-19 Vaccine, that if I wasn’t President, you wouldn’t be getting that beautiful ‘shot’ for 5 years, at best, and probably wouldn’t be getting it at all. I hope everyone remembers!”

President Trump said about the COVID-19 vaccine in an interview on Fox News in March 2021: “It works incredibly well. Ninety-five percent, maybe even more than that. I would recommend it, and I would recommend it to a lot of people that don’t want to get it and a lot of those people voted for me, frankly.

“But again, we have our freedoms and we have to live by that and I agree with that also. But it’s a great vaccine, it’s a safe vaccine, and it’s something that works.”

On many occasions, President Trump has said that he is not in favor of vaccine mandates.

An environmental attorney, Mr. Kennedy founded Children’s Health Defense, a nonprofit that aims to end childhood health epidemics by promoting vaccine safeguards, among other initiatives.

Last year, Mr. Kennedy told podcaster Joe Rogan that ivermectin was suppressed by the FDA so that the COVID-19 vaccines could be granted emergency use authorization.

He has criticized Big Pharma, vaccine safety, and government mandates for years.

Since launching his presidential campaign, Mr. Kennedy has made his stances on the COVID-19 vaccines, and vaccines in general, a frequent talking point.

“I would argue that the science is very clear right now that they [vaccines] caused a lot more problems than they averted,” Mr. Kennedy said on Piers Morgan Uncensored last April.

“And if you look at the countries that did not vaccinate, they had the lowest death rates, they had the lowest COVID and infection rates.”

Additional data show a “direct correlation” between excess deaths and high vaccination rates in developed countries, he said.

President Trump and Mr. Kennedy have similar views on topics like protecting the U.S.-Mexico border and ending the Russia-Ukraine war.

COVID-19 is the topic where Mr. Kennedy and President Trump seem to differ the most.

Former President Donald Trump intended to “drain the swamp” when he took office in 2017, but he was “intimidated by bureaucrats” at federal agencies and did not accomplish that objective, Mr. Kennedy said on Feb. 5.

Speaking at a voter rally in Tucson, where he collected signatures to get on the Arizona ballot, the independent presidential candidate said President Trump was “earnest” when he vowed to “drain the swamp,” but it was “business as usual” during his term.

John Bolton, who President Trump appointed as a national security adviser, is “the template for a swamp creature,” Mr. Kennedy said.

Scott Gottlieb, who President Trump named to run the FDA, “was Pfizer’s business partner” and eventually returned to Pfizer, Mr. Kennedy said.

Mr. Kennedy said that President Trump had more lobbyists running federal agencies than any president in U.S. history.

“You can’t reform them when you’ve got the swamp creatures running them, and I’m not going to do that. I’m going to do something different,” Mr. Kennedy said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, President Trump “did not ask the questions that he should have,” he believes.

President Trump “knew that lockdowns were wrong” and then “agreed to lockdowns,” Mr. Kennedy said.

He also “knew that hydroxychloroquine worked, he said it,” Mr. Kennedy explained, adding that he was eventually “rolled over” by Dr. Anthony Fauci and his advisers.

MaryJo Perry, a longtime advocate for vaccine choice and a Trump supporter, thinks votes will be at a premium come Election Day, particularly because the independent and third-party field is becoming more competitive.

Ms. Perry, president of Mississippi Parents for Vaccine Rights, believes advocates for medical freedom could determine who is ultimately president.

She believes that Mr. Kennedy is “pulling votes from Trump” because of the former president’s stance on the vaccines.

“People care about medical freedom. It’s an important issue here in Mississippi, and across the country,” Ms. Perry told The Epoch Times.

“Trump should admit he was wrong about Operation Warp Speed and that COVID vaccines have been dangerous. That would make a difference among people he has offended.”

President Trump won’t lose enough votes to Mr. Kennedy about Operation Warp Speed and COVID vaccines to have a significant impact on the election, Ohio Republican strategist Wes Farno told The Epoch Times.

President Trump won in Ohio by eight percentage points in both 2016 and 2020. The Ohio Republican Party endorsed President Trump for the nomination in 2024.

“The positives of a Trump presidency far outweigh the negatives,” Mr. Farno said. “People are more concerned about their wallet and the economy.

“They are asking themselves if they were better off during President Trump’s term compared to since President Biden took office. The answer to that question is obvious because many Americans are struggling to afford groceries, gas, mortgages, and rent payments.

“America needs President Trump.”

Multiple national polls back Mr. Farno’s view.

As of March 6, the RealClearPolitics average of polls indicates that President Trump has 41.8 percent support in a five-way race that includes President Biden (38.4 percent), Mr. Kennedy (12.7 percent), independent Cornel West (2.6 percent), and Green Party nominee Jill Stein (1.7 percent).

A Pew Research Center study conducted among 10,133 U.S. adults from Feb. 7 to Feb. 11 showed that Democrats and Democrat-leaning independents (42 percent) are more likely than Republicans and GOP-leaning independents (15 percent) to say they have received an updated COVID vaccine.

The poll also reported that just 28 percent of adults say they have received the updated COVID inoculation.

The peer-reviewed multinational study of more than 99 million vaccinated people that Mr. Kennedy referenced in his X post on March 7 was published in the Vaccine journal on Feb. 12.

It aimed to evaluate the risk of 13 adverse events of special interest (AESI) following COVID-19 vaccination. The AESIs spanned three categories—neurological, hematologic (blood), and cardiovascular.

The study reviewed data collected from more than 99 million vaccinated people from eight nations—Argentina, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, New Zealand, and Scotland—looking at risks up to 42 days after getting the shots.

Three vaccines—Pfizer and Moderna’s mRNA vaccines as well as AstraZeneca’s viral vector jab—were examined in the study.

Researchers found higher-than-expected cases that they deemed met the threshold to be potential safety signals for multiple AESIs, including for Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS), cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), myocarditis, and pericarditis.

A safety signal refers to information that could suggest a potential risk or harm that may be associated with a medical product.

The study identified higher incidences of neurological, cardiovascular, and blood disorder complications than what the researchers expected.

President Trump’s role in Operation Warp Speed, and his continued praise of the COVID vaccine, remains a concern for some voters, including those who still support him.

Krista Cobb is a 40-year-old mother in western Ohio. She voted for President Trump in 2020 and said she would cast her vote for him this November, but she was stunned when she saw his response to President Biden about the COVID-19 vaccine during the State of the Union address.

“I love President Trump and support his policies, but at this point, he has to know they [advisers and health officials] lied about the shot,” Ms. Cobb told The Epoch Times.

“If he continues to promote it, especially after all of the hearings they’ve had about it in Congress, the side effects, and cover-ups on Capitol Hill, at what point does he become the same as the people who have lied?” Ms. Cobb added.

“I think he should distance himself from talk about Operation Warp Speed and even admit that he was wrong—that the vaccines have not had the impact he was told they would have. If he did that, people would respect him even more.”

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International4 days ago

International4 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoGOP Efforts To Shore Up Election Security In Swing States Face Challenges