International

From bench to boardroom: 20 of the most influential biopharma R&D executives in drug development

Biopharma is no stranger to major scientific innovations, but when you talk to the movers and shakers in the field on who has influenced their work the most, you start to hear a few key names over and over again.

That was certainly the case when we polled

Biopharma is no stranger to major scientific innovations, but when you talk to the movers and shakers in the field on who has influenced their work the most, you start to hear a few key names over and over again.

That was certainly the case when we polled industry executives on who they viewed as the R&D luminaries of note — men and women across the drug development spectrum who take major biological and chemical breakthroughs and spin them like gold into medical miracles. These are the people who opened doors to new fields of drug research, laying the foundation for much of the work now underway in the clinic.

Whether it’s next-gen cell therapies or even the once oft-forgotten field of vaccines, our list of the 20 most influential R&D executives runs the gamut on innovation. The key traits that tie them all together are persistence, collaboration and the inability to let a good idea go uninvestigated.

More than that, these are not necessarily the executives who take the most drugs over the finish line, but rather those whose work sets the table for other innovations down the road and makes the impossible possible. And before you feel inspired to ask why we left out so many extraordinary scientists, please understand that we have enormous respect for breakthrough science legends like Jim Allison and Jennifer Doudna and Phil Sharp and so many other academic Nobel prize-winners who created entire pipelines that are still filling up with new drugs.

This time we’re sticking with industry executives.

Here’s our list. Hope you enjoy — Kyle Blankenship

- David Altshuler

- Patrick Baeuerle

- Jay Bradner

- David Chang

- Stanley Crooke

- Frank Fan

- Carole Ho

- Kathrin Jansen

- Katalin Karikó

- Cynthia Kenyon

- John Leonard

- John Maraganore

- Frank McCormick

- Richard Mulligan

- Roger Perlmutter

- Aviv Regev

- Jude Samulski

- Richard Scheller

- David Schenkein

- George Yancopoulos

- Highlights Co-founder of the Broad Institute, academic behind series of projects to interpret the human genome, architect of Vertex’s post-CF R&D strategy

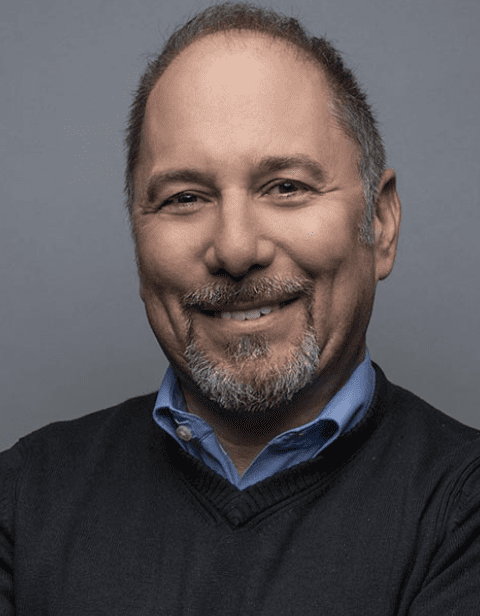

David Altshuler

In 2011, Harvard geneticist David Altshuler got a call from Jeff Leiden, asking if he would join the board of Vertex, the troubled company the longtime academic and executive had agreed to run. Leiden being a friend — and board seats being the low-risk endeavors they are — Altshuler agreed.

By 2014, the famed professor had agreed to take over R&D for what would soon become one of the most financially and scientifically successful biotechs in the world. Altshuler can take some credit for that: Trikafta, the drug that ultimately changed the lives of most cystic fibrosis medicines, was synthesized and developed under his leadership. But his legacy may ultimately have to do with what comes next and the scientific blueprint Altshuler has in some sense been building since his earliest days as a scientist.

Altshuler made his name believing in and proselytizing the power of genetics — and specifically the power of big teams mining large amounts of genetic data — to explain human disease at a time when not everyone believed it would. Now that that work has become mainstream, informing work at every pharma and biotech, he’s trying to apply it in a way to making drugs in a way no one else has.

As an undergraduate at MIT in the 1980s, Altshuler worked with Richard Mulligan on the earliest attempts at curing sickle cell disease with gene therapy, before moving on to Doug Melton’s lab at Harvard to try to restore neurons in the brain and retina.

“So I’ve been thinking about, for literally 30 years, how do you get to the underlying cause of disease?” Altshuler said in an interview. “And then, how do you address that underlying cause rather than treat symptoms?”

So in 1997, after wrapping his MD-PhD, he joined Eric Lander on the Human Genome Project. Although sequencing the genome was, for many, the clear way of getting at the roots of human health, not every scientist thought it was a good career move. The grand project felt like number crunching, a kind of industrialized science removed from the creative genius of the lone investigator.

“They all said, ‘You’re crazy, you’re going to destroy your career, that’s a factory project, that’s blue collar work,’” he told GV earlier this year. “There’s no questions; it’s just a bunch of machines.”

Altshuler would spend a decade-and-a-half proving them wrong. He led a series of projects — the SNP consortium, HapMap, and the 1000 Genomes Project — that used the data and the technologies unleashed by the genome project to show the complex combination of genes that undergirded and raised the risk for common diseases such as heart disease, stroke and depression, or governed how well someone responded to a drug. In 2003, he co-founded the Broad Institute, providing a home for new, large collaborative projects and, ultimately, luminaries such as Aviv Regev, Feng Zhang and David Liu.

It also gave Altshuler a rare thing for an academic: experience running large projects with lots of moving parts.

By 2014, the scientific landscape had changed. In part thanks to his projects, there had been numerous genomic discoveries with applications for medicine, including rare variations that pointed directly to therapies: patients genetically endowed with high risk of heart attack, for example, or with virtually unlimited pain tolerance.

“And I became more interested in how we would use [these discoveries] to develop therapies than in cataloging more,” Altshuler said.

As a board member, he also fell in love with the science-centric organization Leiden was building, one that invested almost everything in research and was in the process of dramatically altering one of the most common fatal genetic diseases. As CSO, his job was to come up with a scientific strategy that could match the corporate strategy — one that could produce innovation after innovation.

A few months after taking over, in the summer of 2014, Altshuler stood up in front of every Vertex employee and revealed a new plan: The company would no longer work on just any disease, as they had been doing. Instead, they would focus on diseases where they deeply understood the underlying cause — no Alzheimer’s work, for example — and had a reasonable chance at correcting it. And they would buy whatever tool they needed to make it happen.

It was a hard pivot from how Vertex and most companies had viewed biotech: developing a tool and then finding a use for it. And some staff scientists were sad to part with potent molecules they had developed for years and hoped to find a use for.

Yet it laid the basis for the pipeline Vertex is now developing, including the CRISPR therapy that has already seemingly cured a handful of patients with sickle cell disease. It helped lead to their clinical programs tackling AATD and genetically defined kidney disease, as well as their acquisitions of a CRISPR therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy and cell therapy for diabetes.

The verdict on the approach is still out: Key programs, such as AATD, have fallen behind. But if the company can manage to execute on even a portion of those diseases, the impact could be as profound, if not more so, as the impact Vertex has already had on CF.

— Jason Mast

- Highlights Former CSO of Micromet, former VP of research at Amgen, current executive partner at MPM Capital where he’s helped launch six companies

Patrick Baeuerle

While most kids hope to find mountains of toys under the Christmas tree, it was chemistry kits and microscope sets that got a young Patrick Baeuerle excited.

Baeuerle took that passion all the way to the University of Konstanz in Germany, where he studied biology, and later to the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, where he earned his PhD. He conducted postdoc research with Nobel laureate David Baltimore at MIT’s Whitehead Institute, one of the world’s top research institutions for molecular biology and genetics.

Now, he’s lauded as a pioneer in the bispecific space, where he nabbed the industry’s first FDA approval for the emerging class of antibodies.

But before all that, Baeuerle took a job teaching biochemistry at the University of Freiburg in 1994. The scientist spent a couple of years in his 30s unraveling the principles of biology at Freiburg. Then he realized he wanted to make more of an impact.

“I had a deep look into the academic world, and then it was clear to me that I’d rather go into biotech,” Baeuerle told Endpoints News. “And ever since, I have (had) an enormous pleasure in developing novel therapeutics, particularly cancer therapeutics.”

The professor packed his bags for California to head small molecule drug discovery at a young biotech called Tularik. The company was focused on cell signaling and how to control gene expression to treat cancer, inflammation and metabolic diseases. Baeuerle left after a short two years, and in 2004, the company was snapped up by Amgen for over $1 billion.

While he was still working at Tularik, Baeuerle was approached by a cancer drug developer called Micromet, which was based in Maryland but had an R&D hub in Germany. They asked Baeuerle if he was interested in running the company’s research as CSO.

“I was ready to go,” Baeuerle said, adding that he wanted to be closer to his father in Europe, and the prospect of more responsibility was exciting.

Over the next 13 years, Baeuerle helped Micromet become a pioneer in the development of T cell-engaging bispecific antibodies, or antibodies that enable T cells to detect and destroy cancer cells that are hard to recognize. He eventually led the company’s candidate blinatumomab to a swift FDA approval for patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 2014 (that drug is now marketed as Blincyto), marking the industry’s first approved bispecific antibody.

Since then, the space has erupted, with the FDA counting about 100 candidates in or near the clinic as of May. Blincyto brought in $380 million last year — and everybody wants a piece of the market. AbbVie fronted $90 million to get a BCMA bispecific from Teneobio back in 2019, a small biotech that Amgen put down $900 million to acquire last month. Regeneron has spent millions developing bispecific antibodies, and last summer demonstrated that combining a bispecific with a PD-1 therapy could help clear solid tumors in mice. And at the end of last year, Genentech’s bispecific cleared two Phase III studies for diabetic macular edema, where it went head-to-head with Regeneron’s Eylea.

In 2012, familiar patron Amgen set its sights on Micromet, striking a $1.16 billion deal to buy out the company and its cancer drugs.

“This has been a pretty long campaign,” then Amgen R&D chief Roger Perlmutter told Endpoints News editor John Carroll in 2012. “I’ve been carrying a torch for (CSO) Patrick Baeuerle at Micromet for a long time. I believe they have found a better way to kill tumor cells.”

Baeuerle stayed on the team until 2015, then left for his current position at MPM Capital.

As executive partner at MPM, the scientist has helped launch six new companies: Harpoon Therapeutics, iOmx Therapeutics, Maverick Therapeutics (which was acquired by Millennium Pharmaceuticals), TCR² Therapeutics, Werewolf Therapeutics and Cullinan Oncology.

“I think it’s important not to plan too far ahead,” he said. “You cannot plan to be a professor in 10 years, or be a CEO in 15 years. You should look at the next step, and wherever you are right now, do the very best there, and then create opportunities.”

— Nicole DeFeudis

- Highlights Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research president, co-founded C4 Therapeutics, leader in the protein degradation space

Jay Bradner

Novartis research head and serial entrepreneur Jay Bradner has said his interest in drug discovery traces back to his time treating patients at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

“After I was trained as a medical doctor, I was struck by the inadequacy of our medicines for cancers,” Bradner told the Boston Globe back in 2015.

“For sure, witnessing the impossible challenge of cancer and other severe illnesses on the wards in medical school galvanized a committed interest in chemical biology, to imagine new types of medicines,” he told Endpoints News in an email.

Since taking the helm at the esteemed Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, Bradner now leads a dogged team of researchers aiming after the “highest hanging fruit in drug discovery,” and he’s become an influential leader in protein degradation, a new approach to destorying so-called “undruggable” targets — i.e. those that can’t be hit with conventional antibodies or small molecules.

“My least favorite term in our field is ‘undruggable target,’” he said.

The Illinois native got his bachelor’s in biochemistry from Harvard University in 1994, then completed his medical degree at the University of Chicago before joining Dana-Farber as a physician-scientist. He left for Novartis in January 2016, and within a few short months, took over as the second president of the NIBR.

Bradner has inked some big deals for Novartis, including a pact with the Gates Foundation to find an in vivo approach to curing sickle cell disease, and a collaboration with UC Berkeley back in 2017 on protein degraders.

The entrepreneur has also co-founded five companies, including C4 Therapeutics, which recently hopped onto Nasdaq in a $180 million-plus public debut. The biotech was one of the first companies in the industry to enter the clinic with a protein degrader. Last March, Novartis joined up with Orionis to discover new protein degraders and other small molecule drugs aimed at “historically elusive targets,” according to Bradner.

The scientist has long been a proponent of open science, and when his lab at Dana-Farber discovered JQ1 — a small molecule that blocks the epigenetic enzyme bromodomain 4 — he decided to share it with other researchers with no restrictions. Other researchers have since found a smattering of potential applications, including most recently as a way to boost CAR-T therapy.

“We can move faster to deliver definitive therapeutic responses if we work more openly together,” Bradner wrote in an email. “Yet there are powerful incentives to work more privately, in industry but also in academia where priority is exaggerated and biotechs now arise in advance of scholarly publication (so-called ‘stealth-mode’).”

When asked about his proudest accomplishment, Bradner cited his children, who he was on vacation with at the time.

“Jennifer and I have wonderful children, and we are both very proud of our family life,” he said, adding: “Drug hunting is humbling work, and I am surely just getting started.”

— Nicole DeFeudis

- Highlights Guru behind Kite’s Yescarta, pioneer of allogeneic CAR-T

David Chang

When Novartis’ Kymriah first crossed the finish line in 2017, it appeared that science fiction was now established medicine.

Using attenuated virus transports to genetically engineer human T cells into specialized tumor killers, CAR-T therapies represented a massive breakthrough for the most dire patients with blood cancers — a potentially curative option for patients at the absolute end of the treatment spectrum.

After Novartis’ success came a quick second CAR-T therapy — a groundbreaker in non-Hodgkin lymphoma — Yescarta from Gilead’s Kite. That feat tied in no small part to Kite’s CMO and head of R&D, David Chang, a respected researcher in his own right with a track record of success at Amgen and in academia before that.

Now, three years into his stint as CEO at Allogene Therapeutics, Chang is trying to take lessons from developing an autologous CAR-T — using T cells derived from the patient and engineered ex vivo — into allogeneic, or “off-the-shelf,” CAR-T therapies that could theoretically cut through the significant manufacturing and logistical hurdles the field currently faces.

Earning his bachelor’s at MIT and his MD and PhD at Stanford, Chang cut his teeth in academia as an associate professor of medicine and of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA after clinical stints at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a fellowship in medical oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at Harvard.

In 2002, Chang made his big jump to industry, kickstarting a 12-year stint at Amgen, including in the roles of global head of development and head of hematology-oncology, which would eventually dovetail nicely with his work at Kite.

While there, Chang worked on developing personalized therapy strategies for Vectibix as well as leading development of Blincyto, a bispecific T cell engager antibody for acute lymphocytic leukemia. Chang’s time at Amgen also put him in contact with another influential on our list — Roger Perlmutter, who would go on to head the Keytruda launch at Merck.

On top of his current role at Allogene, a company co-founded by serial biotech entrepreneur and the man with the golden touch, Arie Belldegrun, Chang serves as a director at A2 Biotherapeutics and Peloton Biotherapeutics, and as a venture partner at Vida Ventures.

— Kyle Blankenship

- Highlights Pioneer and unyielding defender of antisense, founder and longtime CEO of Ionis, founder and CEO of N-Lorem, a non-profit to build N-of-1 antisense therapies for patients with ultra-rare diseases

Stanley Crooke

A little over 30 years ago, Stanley Crooke, a wunderkind executive at SmithKline, decided that he was sick of the way pharma companies developed drugs.

They created, he noted, baroque commercial bureaucracies that weighed down the company and detracted from research. And the way they did research was grossly inefficient, random almost. You took molecules from the soil or some other source, threw them at tissues or cells in a lab and looked at what stuck.

He decided that he would build a company that focused only on R&D, passing off the molecule to a larger pharma for commercialization and even late-stage development. And he would find a way to rid himself of randomness, to create drugs rationally, to design them.

Had Crooke had this revelation a decade or two later, he may have settled on any of a few methods to achieve that goal. But at the time, the technologies future generations of scientists would use to rationally design drugs — billion-dollar, disease-changing breakthroughs such as CRISPR and small interfering RNAs — had scarcely been discovered in nature, let alone turned into something bio-engineers could use. So Crooke settled on antisense, a nascent method of utilizing strands of RNA to control protein production.

The decision would send him down an over three decade-long campaign, as he defended and developed a field that the rest of the industry abandoned, leading his company to develop a landmark drug, other scientists to found their own companies aimed at a wide swath of disorders and the rise of one of the most unexpected and potentially transformational new eras of medicine.

Crooke acknowledged from the outset how difficult it could be, telling investors it would take 20 years and $2 billion to prove the technology as he pitched them on Isis Pharmaceuticals. (It was renamed Ionis in 2015 for obvious reasons.)

Fortunately, Crooke was tenacious. Born in poverty and raised at times by his grandmother, mother and stepfather, he was the first in his family to graduate high school. He drifted through college until an administrator recommended he consider grad school. He picked Baylor, where he found a mentor who could match him. Soon, he was soaring the ranks in pharma, running oncology for Bristol and tasked with repeating SmithKline’s Zantac success.

It was all an appetizer for what he would endure at Isis. As the 1990s progressed, skepticism around antisense grew. It was impossible to get the RNA strands into the right cells. The field’s pioneering papers turned out to be plain wrong. Other antisense companies, most notably Gilead, pivoted to other fields. “Antisense,” a common refrain went at the time, “was nonsense.”

And yet Crooke, intense, sometimes even imposing and yet fiercely charismatic — deputies followed him from SmithKline to Isis and stayed for decades — stuck to the technology, turning himself into a walking antisense encyclopedia (the company never hired a CSO, Crooke serving as a de facto one alongside his CEO duties), and enduring repeated trial blowups and layoffs to get the first antisense drugs approved in 1999 and 2013.

Neither were major successes, but in 2016 came Spinraza, the first drug ever approved for the devastating genetic disease spinal muscular atrophy. The era of antisense was at hand. Quickly, other startups popped, riffing on the progress Crooke and his team made to go after muscular dystrophies, neurodegeneration, cystic fibrosis and other devastating diseases.

Now, in addition to Ionis’ extensive pipeline of therapies, scientists are using antisense to do what had long seemed impossible: building custom therapies for patients with ultra-ultra-rare diseases, by identifying the mutation and designing a matching antisense strand to silence it.

It’s also where Crooke has decided to devote the rest of his career. He retired from Ionis last year and now runs n-Lorem, a nonprofit dedicated to trying to make these so-called “n-of-1” therapies available to as many patients as possible.

— Jason Mast

- Highlights Inventor of China’s first major CAR-T, now on the cusp of FDA approval

Frank Fan

Frank Fan almost missed the deadline for submitting the ASCO abstract that would make him famous virtually overnight.

Becoming famous, to be sure, was not exactly part of the plan — much less to make a statement for Chinese biotech as an industry or blaze a trail for others to come. For the three or so years leading up to that spring day in 2017, Fan and his small team at Nanjing Legend Biotech had been keeping their heads down, collecting clinical data on one of the first CAR-Ts directed against BCMA — then still an emerging target for multiple myeloma. But as they started seeing impressive patient responses, the scientists began to wonder about bringing their cell therapy to the US. To do that, they needed at least some investigators to be willing to help them.

So Fan had his eyes set on ASCO, the largest meeting of American clinical oncologists, even though he didn’t even have a membership. Borrowing a university friend’s login, he scrambled to submit his abstract at the very last minute.

The abstract, detailing results from Legend’s first trial, was accepted as a late breaker and scheduled for presentation in a large seminar room. Among 35 relapsed, drug-resistant patients treated with what was then known as LCAR-B38M, the overall response rate was 100%, with as many as 74% qualifying for a stringent complete response. “It’s rare to see such high response rates,” commented one expert.

Yet coming from an unknown Chinese company, the initial reaction was a mix of amazement and skepticism, recalled Ying Huang, who sat in the room as a biotech analyst. “Most people in the audience basically thought that it’s hard to believe,” Huang, now Legend’s CEO, said.

J&J took a leap of faith and surprised the industry again months later, throwing its weight (and $350 million in cash) behind the candidate, which was eventually christened cilta-cel.

In retrospect, Legend’s rise to fame almost looked meteoric. But Fan remembers those early days when he was tasked with starting an R&D group within the CRO GenScript, given some money and assigned one employee to help. As he recruited more and purchased equipment, he managed to convince management to clear out a storage room for him to build a lab and office.

While he was initially instructed to also research nanobodies — and his team did generate some candidates — Fan was much more intrigued by CAR-T. Trained as a transplantation surgeon and well versed in B cell immunity, he became fascinated when Emily Whitehead’s story took the scientific community by storm around 2014.

At that point in China, cell therapy was a minimally regulated medical procedure and, more than anything, an easy moneymaker. Almost every renowned hospital had a dedicated department, and a number of startups were formed to capitalize on what some saw as a $10 billion market.

But he was uninterested in that path, nor was he eager to join the CD19 gold rush. Rather, Fan picked out BCMA, or B cell maturation protein, before learning about anyone else working on that target, and held a high standard for the design of Legend’s first clinical study, an investigator-initiated trial. Then he knocked on doors to look for doctors who would help test the drug.

“I remember one local hospital, I visited five times and eventually their ethical committee just ignored us because we were nobody,” he said, adding that the generally conservative attitude toward new therapeutic approaches might have also been in play.

Once they secured the first site through an old friend, though, referrals began pouring in, paving the way for them to land the first IND certificate for a CAR-T therapy in China history. Those data from 74 patients — an unusually large size for an IIT — also led Legend straight to a Phase Ib stateside with the FDA’s blessing. It is now poised to become the second-ever BCMA CAR-T to be approved in the US, lining up right after Bristol Myers Squibb’s Abecma.

“So I think that’s really the beginning of a new era here” in China, Huang said, “because we’re starting to show that these companies can do good science, can innovate and can generate high quality clinical data.”

— Amber Tong

- Highlights Genentech veteran, CMO of Denali Therapeutics

Carole Ho

Carole Ho spent a lot of time at prestigious institutions before making her way to Denali Therapeutics where she’s helping lead the charge to solve the blood-brain barrier puzzle.

The Denali R&D chief and CMO got started as an undergrad at Harvard University, studying biochemical sciences and graduating magna cum laude. Then, she went to med school at Cornell University and followed that up with a postdoc at Stanford University in neurobiology. Ho topped it all off by returning to Harvard for her residency in neurology, ultimately climbing the ranks to chief resident.

While she didn’t start out her post-residency career in biotech, Ho eventually made her way to Genentech as a vice president of early clinical development in 2007. Also at Genentech at that time were Denali co-founders Marc Tessier-Lavigne, Ryan Watts and Alex Schuth.

About a month after Denali’s launch in 2015, Ho joined the company and has held the CMO role ever since. It’s been under her stewardship that Denali has advanced a whole slate of preclinical and clinical candidates attempting to break past the blood-brain barrier and deliver reliable therapeutics.

It’s an area where many have tried and failed thus far, and Ho’s research at Denali is being closely watched by both the market and Big Pharma. The company had built up considerable hype for its pipeline since launching with the biggest biotech Series A at the time, and Ho has helped steer potential therapeutics for tough-to-crack diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as rarer conditions like Pompe disease and Hunter syndrome.

The candidate for Hunter syndrome released a new cut of data in July, which showed positive signs affecting biomarkers specifically related to the disease. But many analysts had keyed more on neurofilament, an exploratory biomarker thought to be implicated in a wide range of neurodegenerative diseases. An outside consensus had emerged that, if the Hunter syndrome program trended toward decreasing neurofilament, it would bode well for Denali’s other candidates and the neuro field as a whole.

Instead, patients saw their average neurofilament levels increase, disappointing investors and sending Denali’s stock down 15% in a day.

The Denali technology itself that Ho helped bring forward relies on what’s known as the transferrin receptor. Using the body’s natural iron transporters — which can get past the barrier and get needed nutrients into the brain — Ho and her team aim to attach drugs to the receptors in a piggyback fashion.

It’s not just one kind of therapeutic that Denali can attach, either. Ho and the company have been working on product candidates that use antibodies, enzymes, proteins and oligonucleotides.

What’s next for Denali? Ho will almost certainly be at the forefront of any new developments, continuing the necessary work in trying to solve the blood-brain barrier puzzle, a riddle that could prove the key to treating a raft of disorders.

— Max Gelman

- Highlights Pioneer behind HPV Vaccine, Prevnar 13 and leader of Pfizer’s Covid-19 vaccine effort

Kathrin Jansen

Before the pandemic, few in pharma cared much about vaccines: With rare exception, infectious diseases felt like a developing world problem, many of them snuffed out by inoculations scientists made decades, if not a century, ago. The money was in cancer, neurology, diabetes — the diseases of the rich world.

So when Covid-19 broke out, few companies could call on someone like Kathrin Jansen, an unflappable and tenacious believer in vaccines who had already led the development of two of the most important vaccines of the last two decades, each scientific feats many doubted were possible. So maybe it was a coincidence, and maybe it wasn’t, that Pfizer, the company that did, was also the first to get its Covid-19 vaccine past the finish line.

The daughter of an East German doctor who snuck his family across the border shortly before the Berlin Wall went up in 1961, Jansen earned a PhD at Philipps-University in Marburg and then bounced between post-grad jobs at Cornell, MGH and the Glaxo Institute for Molecular Biology in Geneva before an old colleague invited her to interview for a job at Merck, the legendary company that had developed the vaccines for measles, mumps, and hepatitis B.

But Merck, rumors at the time went, was considering leaving vaccines, and Jansen was first assigned to a project on diabetes. She promptly showed it had no chance of success. “We couldn’t reproduce a single thing that was described,” Jansen told STAT last year.

Quickly, Jansen fell in love with a different project: a vaccine for human papillomavirus, or HPV, the virus that causes cervical cancer. She pushed the company to abandon its current method of trying to display the vaccine in insect cells and instead use yeast, like it had with the HBV vaccine. She showed the method could produce HPV proteins that formed into “virus-like particles,” making it ultra-visible to the immune system.

But that was only one hurdle. Merck executives were wary after suffering the failure of their herpes vaccines. And unlike other viruses, Merck couldn’t culture HPV in the lab, meaning it couldn’t study it directly and, worse, couldn’t test to see if the vaccine induced antibodies in volunteers. Jansen promised she would develop proper efficacy tests and then again had to convince them that new tests would work.

“As so often with new technologies or approaches, the efforts to do the work and to convince scientists both internally and externally that the approach was justified were significant,” she recalled in a 2010 perspective. “Many scientists strongly believed that this would be difficult if not impossible to do.”

Sure enough, when the data came back, the vaccine showed 100% protection against HPV. It is now estimated to have saved potentially millions of lives around the world.

Edward Scolnick, Merck’s longtime R&D chief, said Jansen should have been put in charge of their vaccines division, but she wasn’t, and she left for biotech — only to be pulled back in 2006, when Wyeth needed someone with elite scientific expertise. At the time, the company was trying to develop a follow-on to pneumococcal vaccine Prevnar 7, one that could guard against more than just seven strains of bacteria.

It was a delicate task of engineering, intricately assembling proteins from 13 bacteria onto a sugary backbone and then figuring out a way to make sure you had actually done it right. But, under Jansen’s direction, it worked, leading to the blockbuster Prevnar 13.

Pfizer reaped the benefits of that work after it bought out Wyeth in 2009. Jansen continued on for the storied pharma, developing the follow-up Prevnar 20 and going after big, intractable targets, such as RSV and drug-resistant bacteria.

Some of those efforts fell short, but in 2018, Jansen, always keeping her eye on the next big thing, brokered a $120 million deal to team with BioNTech on flu vaccines made from mRNA. Three years later, she led 650 scientists from the two companies as they pivoted the project to coronavirus and overtook Moderna in a race to build the fastest vaccine. In November, it proved not only the first but also one of the most potent vaccines ever: 95% effective.

“This is a historical moment,” Jansen told The New York Times when the news broke. “This was a devastating situation, a pandemic, and we have embarked on a path and a goal that nobody ever has achieved — to come up with a vaccine within a year.”

Now it seems every biotech and investor is interested in vaccines. And Jansen will have her hands full: Pfizer has announced plans to continue with mRNA, building new vaccines on their own, no BioNTech involved.

— Jason Mast

- Highlights Pioneered modified mRNA technology used in BioNTech and Moderna Covid-19 vaccines

Katalin Karikó

Growing up in Hungary, Katalin Karikó developed fast an interest in biology, ever since she watched her father — a butcher — prepare various meats for his customers. It sparked a curiosity that ultimately led her to invent one of the key aspects of the messenger RNA technology used in two lifesaving Covid-19 vaccines.

Karikó made her way to the US in the 1980s after immigrating with just $1,200 cash sewed into her daughter’s teddy bear. She soon found a job at the University of Pennsylvania and began research into synthetic mRNA, though without much support at first.

She applied for grant after grant and faced rejection after rejection. Most — if not all — who reviewed her research described mRNA as an interesting field to explore but were scared off by the violent immune responses mRNA triggered in animal models.

Eventually, her bosses at UPenn demoted her, but Karikó remained convinced of mRNA’s potential. She ended up teaming with her colleague Drew Weissman to try to get around the immune response issue, and the pair came up with a solution: By modifying one of the nucleosides that make up mRNA, the molecule could potentially sneak past the body’s natural defenses.

The theory worked and she set out with Weissman to launch a biotech in 2006. But after UPenn licensed out her patent in 2012 and she was forced out of business, Karikó decided she was done with academia and took a role at BioNTech as a senior vice president.

It’s there where the modified nucleoside proved key. The research that Karikó had worked on for decades ended up as the basis for both BioNTech’s Covid-19 vaccine as well as Moderna’s; the latter also licensed her earlier patent.

As the pandemic and vaccine trials dragged on, more and more people took notice of Karikó’s work. She’s garnered significant media attention from publications ranging from the New York Times to the New York Post. And Moderna founder Derrick Rossi has called for Karikó to win the Nobel Prize for her research.

Prominent investors and big pharmas are now pouring money into mRNA, hope to get a piece of the technology Karikó pioneered. In terms of the future, the scientist has said she envisions mRNA to be the basis for continued therapeutic use, and not just in infectious diseases. One potential application could come in the form of a Neosporin-like spray, where individuals can spritz the drug on open wounds and help induce quicker healing.

— Max Gelman

- Highlights Godmother and semi-savior of anti-aging research, VP of aging research at stealthy Google anti-aging behemoth Calico

Cynthia Kenyon

When Cynthia Kenyon started her lab, she wouldn’t let her colleagues or graduate students even write down what they were working on. The field was so taboo, so fraught with failure and denuded with snake-oil salesmen that just mentioning it on a grant application could get your reviewer laughing and send your file straight into the trash.

The secret work? Aging research.

Over nearly three decades, Kenyon rescued the anti-aging field from the clutches of tonic-peddling con men and turned it into a broadly respectable discipline, paving the way not only for a generation of academics whose work has helped elucidate the basic biology of aging but also a wave of biotechs dedicated to turning those insights into therapies to enhance longevity or just curb aging-related diseases.

“People thought it would be the end of your career if you went into this field,” Laura Deming, founder and partner of Longevity Fund, a VC focused on anti-aging companies, said last year. “And she started it anew.”

Kenyon, a bright college valedictorian who got her PhD under Nobel laureate Sydney Brenner, was herself discouraged from pursuing the field. “One [colleague] told me that I would fall off the edge of the earth if I studied aging,” she recalled.

She struggled to even find graduate students willing to touch her work. But eventually one did, and the results were profound. They showed that manipulating one gene, called DAF-2, could double the lifespan of nematode worms, a common model organism for studying various features of developmental biology.

Longevity hadn’t been taboo simply because of its association with snake-oil salesmen. Many biologists also felt it was uncrackable, that it was a deeply complex process incorporating too many moving parts to track, or that it is a pristine, simple process beyond the reach of casual genetics: Bodies grow old and then they break. No more mysterious or remediable than the wear on a broken-down 30-year-old minivan.

But Kenyon had just shown a single gene could dramatically alter lifespan, which meant there were probably similar genes in mammals that could do the same. The hunt was on. MIT’s Leonard Guarente soon discovered another gene, SIR2, could do similar things in yeast. In 1999, Kenyon and Guarente teamed to found the first major anti-aging startup, Elixir Pharmaceuticals, eventually winning backing from Bob Nelsen and other top flight investors.

Elixir ultimately fell apart — the science was too early, Nelsen later explained — but it provided an onramp for a wave of biotechs that have the potential to make greater progress. Most notable among them is Google’s anti-aging behemoth Calico, a biotech that Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page endowed with enough cash and latitude to burrow at the basic biology of aging until it comes up with answers that could lead to therapies.

Among the first hires? Kenyon, who was named vice president of aging research. Since then Kenyon, who had been the field’s kindest and most unashamed communicator, has largely curtailed her public activities. And yet she has kept publishing, particularly in the last few years as Calico starts to yield results.

Her influence can be felt across the industry. Calico recently re-upped its collaboration with AbbVie, with the partners committing another $1 billion to hunt for aging and cancer medicines. And longevity startups now seem to crop up like dandelions: Unity, BioAge, Epirium, Gordian. Meanwhile, large and rigorous clinical trials are finally underway, testing for the first time whether repurposed medicines such as metformin can actually slow aging.

“This is the decade,” Deming said. “That’s something that’s never been done before, that’s truly the difference between any time in history.”

If they prove effective — or even if they don’t but another biotech with a new approach does — they may owe much of their success to a young academic who refused to listen to what other scientists told her.

— Jason Mast

- Highlights Former SVP of global pharmaceutical R&D at AbbVie, CEO of Intellia Therapeutics

John Leonard

An entrepreneurial spirit is a must for any chief executive. But how many leading scientists can also say they’ve also built a ranch in Bolivia or started their own cidery?

John Leonard’s path to helming Intellia Therapeutics was not a straight one. After getting his medical degree from Johns Hopkins University, he enrolled in Stanford’s residency program and took a post-doc gig with the NIH studying HIV genetics.

“When I decided to leave the NIH and enter industry, making medicines seemed a logical extension of being a doctor,” he told Life Science Leader back in 2019.

Now, he’s helping lead one of the first CRISPR companies, co-founded by recent Nobel Prize winner and pioneer Jennifer Doudna. And in a landmark study readout in June, the company successfully used CRISPR to edit DNA in humans, using the molecular scissors to cut a gene out of the liver cells of patients with ATTR amyloidosis. It was the first time the long-hailed tool had been used directly in humans.

“This is the result that the field has been waiting for to really scale up,” said Fyodor Urnov, a gene editing expert at UC Berkeley who was not affiliated with the work, told Endpoints at the time.

Leonard’s debut in drug discovery was at Abbott Laboratories, where he was known for his work on HIV drugs Norvir and Kaletra, and the blockbuster Humira, which turned into the world’s top-earning drug. When Abbott spun out AbbVie, Leonard stayed on as SVP of global pharmaceutical R&D.

During his 22-year tenure at Abbott/AbbVie, he also started a ranch in Bolivia with a New York bond trader, and launched Virtue Cider — a craft cider company that was later bought by Anheuser-Busch — along with Greg Hall and Stephen Schmakel, Life Science Leader reported. By the time he retired from AbbVie, he was itching to be part of something new again.

Then he met Nessan Bermingham, a venture partner at Atlas Ventures who had big plans to launch a CRISPR/Cas9 company called Intellia. Leonard agreed to come on as R&D chief. The biotech, co-founded by Doudna, jumped out with a quick and successful IPO in early 2016. A year later, Leonard was tapped as CEO.

Bermingham told Endpoints News at the time:

“At this stage, Intellia requires a CEO with a track record of successful drug development. John was the first to join me in starting Intellia, and was an ideal partner because of his unmatched R&D expertise and biopharmaceutical leadership experience. As I return to my roots in biotech venture capital, I am confident that Intellia, the science and our employees are in great hands.”

As R&D chief and CEO, Leonard steered Intellia’s development of lipid nanoparticles — the microscopic bubbles of fat that are used to deliver mRNA Covid-19 vaccines — for gene editing. It’s what allowed the company to beat rivals to the first in vivo trials and is quickly emerging as the go-to delivery technology for CRISPR and related tools.

“It’s an exciting day, it’s an exciting milestone,” Rodolphe Barrangou, an early CRISPR researcher and a co-founder of Intellia, said at the time. “But we have a ways to go.”

— Nicole DeFeudis

- Highlights Alnylam CEO, guided first approval for RNAi drug patisiran

John Maraganore

Three years removed from its first FDA approval and with three of its trademark RNA interference drugs in the portfolio, it can be easy to forget that Alnylam was once a black sheep in the biotech world, working on tech that just didn’t appear feasible.

But Alnylam’s team, headed by tenacious CEO John Maraganore, eventually crossed the finish line with patisiran in 2018, proving for the first time that siRNA could be delivered effectively to human cells, silencing a gene that caused polyneuropathy in patients with a rare disorder known as hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis.

For Maraganore, it was a win nearly two decades in the making. Founded way back in 2002, Alnylam has been under Maraganore’s steady hand through the highs and lows of the RNAi field, watching as big-name drugmakers splashed in and made a series of ignominious exits out.

In 2011, as the field hit its nadir, Maraganore saw the silver lining that would eventually surround his company’s triumphant commercial turn, telling the New York Times: “A lot of people think it’s winter out there for RNAi. But I think it’s springtime.”

And what a spring it’s been. After the approval of patisiran — marketed as Onpattro — Alnylam followed the approval up with two more RNAi drugs, givosiran and lumasiran, the fruits of Maraganore’s “5×15” plan he launched at the beginning of the past decade.

But, it turns out, Maraganore’s vision didn’t stop at taking three drugs to market, and the future could prove even brighter. Early this year, in anticipation of JPM21, he outlined a plan to make Alnylam into a “top 5” biotech by 2025 by taking six drugs onto market and vastly expanding the company’s clinical trial program to reach a target of four INDs per year.

It’s a lofty goal by any company’s standard, but one undergirded by Maraganore’s steadfast belief in the science and the strength of a team he has spent the bulk of his professional life preparing for primetime.

“Successful and influential R&D leaders need to have the perseverance it takes to follow the science and deliver on the prospects of great ideas,” Maraganore told me over email. “RNAi was just an idea when we got started in 2002. We needed to pioneer through uncertainty, address technology challenges often thought to be unsolvable, and survive multiple near death moments. We needed to take appropriate risks to move the science forward, and we needed to have resolve to succeed.”

— Kyle Blankenship

- Highlights Founded Onyx Pharmaceuticals, named scientific project leader of the National Cancer Institute’s RAS program, UCSF professor

Frank McCormick

Frank McCormick loves a good race — whether it’s against cancer, or in a Pro Formula Mazda.

The 71-year-old English scientist is perhaps best known for his years spent studying RAS-mutated cancers. But at the age of 45, he picked up a new hobby: race car driving. The San Francisco Chronicle reported in 2010 that when McCormick wasn’t in the lab, you’d find him whipping around a track at 140 miles per hour. All the while, he steered efforts to treat various forms of cancer — some of which have proved very successful.

McCormick got his bachelor’s degree in biochemistry from the University of Birmingham in 1972, where he took an interest in understanding cancer on the cellular level. He got his PhD from the University of Cambridge in 1975, and eventually honed in on RAS, a family of proteins that regulate cell growth and survival.

RAS proteins localize to the cell membrane and essentially function as on/off switches. In cancer cells with RAS mutations, the on-state is locked, causing cells to proliferate even in the absence of growth factors. That uncontrolled growth ultimately leads to cancer.

In 1992, McCormick founded Onyx Pharmaceuticals, where he led discovery efforts as CSO that resulted in the approval of Nexavar (sorafenib) for renal cell and liver cancer. The drug is also now approved for thyroid cancer. In 2013, Amgen struck a deal to buy out Onyx for $125 per share. And earlier this year, the big biotech won the industry’s first approval for a KRAS inhibitor with its drug Lumakras.

A slate of other drugmakers is hitting the gas on KRAS, including Mirati, which nabbed breakthrough designation for its candidate adagrasib at the end of June. Eli Lilly jumped into the hunt back in March, and said it planned to put a new small molecule in Phase I later this year. And back in October 2019, Boehringer Ingelheim advanced its pan-KRAS inhibitor into the clinic.

McCormick went on to co-found the small molecule-focused Wellspring Biosciences, and the umbrella biotech BridgeBio, which hit Wall Street back in 2019 with a massive $348.5 million IPO. He’s now a professor at the University of California, San Francisco’s Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. He was also named scientific project leader of the National Cancer Institute’s RAS program.

“For the first time ever, I think I can now see a strategy for eliminating cancer … in the next generation’s lifetime. I don’t think we could’ve said that truthfully even five or 10 years ago,” McCormick told the Washington Examiner back in 2009. “I was pessimistic [about] having a real impact other than just extending life two months here and there. Now I can see a way forward, so I feel much more optimistic.”

— Nicole DeFeudis

- Highlights Gene therapy pioneer, MacArthur “genius” grant winner at 27

Richard Mulligan

Back in 1981, just a year after receiving his PhD in biochemistry from Stanford at the age of 27, the molecular biologist Richard Mulligan won a “genius” grant from the MacArthur Foundation, which is a lucrative, no-strings-attached grant reserved for those with “extraordinary originality and dedication” to their fields.

“More than anything, I think I was just a bit bewildered by the attention given to me as a result of the prize,” Mulligan told Endpoints News.

The grant followed his years of work with his mentor and thesis adviser Paul Berg, the Stanford professor and Nobel Prize winner in chemistry in 1980. Those years shaped him:

“Paul Berg was a truly spectacular mentor and greatly facilitated my development as a scientist. In his laboratory, he conveyed a terrific sense of enthusiasm about the projects undertaken in his laboratory, and made us all feel we were doing the most important work in the world. He was quite unique in this respect. He taught us all how to think crisply about a scientific problem, how to design the ideal experiments to address that problem, and how to communicate our work through seminars and publications in a clear and simple way that even non-experts could understand. These lessons of scientific leadership were invaluable to me as I developed as an independent investigator and grew the size and scope of my laboratory,”

He also said he was “uniquely blessed” by one outstanding mentor after another, from Alexander Rich, to David Baltimore, to Phil Sharp, and outside the scientific world, to Carl Icahn.

Mulligan’s research since then has primarily focused on the development of methods for introducing genes into mammalian cells and the application of gene transfer technology to study basic biology and gene therapies. His early work at MIT led to the development of both retroviral and lentiviral vectors and to the development of general strategies for the production of helper-free stocks of recombinant viruses.

In 1983, as a Searle Scholar at MIT, Mulligan spelled out the details of how promising immunotherapies might be (and he was correct), noting that the basic premise of his early research was focused on genetically modifying either tumor cells or antigen-presenting cells to manipulate immune responses that might lead to more effective immunotherapies for cancer and infectious disease, and perhaps even to new immunosuppressive therapies.

“When my MIT lab was involved in efforts with Drew Pardoll and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins to develop genetically engineered tumor cell-based vaccines, there was considerable skepticism among the chemotherapy-focused old guard as to the promise of immunotherapy,” Mulligan said. “We were able to show in animal models that there could be powerful anti-tumor effects of enhancing the immune recognition of tumors, and I do think such studies by us and many others began to wear down the resistance of the immunotherapy naysayers. So perhaps we contributed in some small way to stimulating interest in immunotherapeutic approaches.”

Since then, Mulligan has proven his genius as a legendary professor and gene therapy pioneer. He’s taught genetics and molecular biology at both Harvard and MIT, in addition to his work at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, among other, more recent industry roles, such as on the board at Biogen, as a portfolio manager at Icahn Capital, and a member of the executive team at Sana Biotechnology.

Mulligan has been recognized over the years as a pioneer in transferring genes into mammalian cells, and his lab has worked to genetically engineer animal viruses into gene transfer vectors.

Scientists have harnessed these specialized tools created in his lab to unravel basic questions about human biology and development, and to develop new gene therapies for the treatment of both inherited diseases and acquired diseases.

— Zachary Brennan

- Highlights Keytruda mastermind, pioneer in immune checkpoint inhibitors

Roger Perlmutter

Roger Perlmutter had a long and illustrious career spanning academia and industry before ever getting his hands on an unproven molecule named pembrolizumab back in 2013, but his legacy — and rightfully so — might always be linked to that blockbuster, now one of the most successful drugs in Big Pharma history.

Starting at Washington University in St. Louis, Perlmutter spent more than 25 years in academia, jumping to posts at Caltech, where he worked alongside famed immunologist Leroy Hood, and then the Howard Hughes Medical Institute before making the fated jump to Merck — for the first time — in 1997.

That start at Merck, where he served as the VP of basic and preclinical research, would start a new career arc that would see Perlmutter become one of the most influential R&D figures in pharma at one of the industry’s largest companies. After just four years at Merck, Perlmutter left for a more-than-decade stint at Amgen and then returned to Merck as president — a role he had been previously passed on during his first tenure — in 2013.

Once there, Perlmutter was immediately handed the keys to pembrolizumab, which later became Keytruda. The drug by that point had shown late-stage promise as an immune checkpoint inhibitor, a drug class with huge promise but limited results, with only Bristol Myers Squibb’s CTLA4 inhibitor ipilimumab (Yervoy) approved on the market.

But in 2013, Keytruda scored its first FDA approval in melanoma, and the race was on. Perlmutter spearheaded an R&D program for Keytruda as both a monotherapy and in combination with a range of targeted immunotherapies that have been breathtaking in terms of return on investment for Merck as well as its influence on the entire oncology field. Keytruda is today the second-bestselling drug in the world behind AbbVie’s aging immunology drug Humira and continues to soak up sales as also-rans from a range of drugmakers look to challenge its mostly unrivaled dominance in PD-(L)1.

Meanwhile, cracking open PD-(L)1 changed the narrative from Yervoy, which still has raised questions on its efficacy profile even alongside Bristol Myers’ own PD-1 drug Opdivo. Now, a range of drugmakers — Merck included — have looked to break into other immune checkpoint classes, including TIGIT, LAG-3 and more to try to replicate (somewhat) Keytruda’s success.

With his crowning achievement and reputation firmly set, Perlmutter made the decision to walk away from Merck this year, but his love of discovery apparently still very much drives him.

In May, Perlmutter was announced as the newest CEO at Eikon Therapeutics, a biotech looking to change the drug discovery game through Nobel-winning next-gen microscopy tech developed at UC-Berkeley. What that challenge holds is still anybody’s guess, but it appears Perlmutter is still very ready to handle the challenge so late in his career.

— Kyle Blankenship

- Highlights Pioneer in machine learning in biology, founder of Human Cell Atlas, head of Genentech early-stage R&D

Aviv Regev

Aviv Regev is an unusual choice for most influential R&D leader for the simple reason that the 50-year-old biologist has worked in biopharma for just a blip compared to some of her peers.

And yet Regev’s appointment last year to run Genentech’s storied, $10 billion early R&D wing represented an acknowledgment of just how much Regev has already changed drug development as an academic and a bet on precisely how Genentech would need to change to stay on top of an industry it founded.

Regev, quick-witted and effusive, with as firm a grasp on machine learning as cancer cell signaling, is at the front of a wave of researchers trying to use new computational tools and methods to make human biology more understandable and, ultimately, more predictable. It’s a broad field where buzzy terms such as machine learning can sometimes get tossed around without a thought, and companies with little background in biology claim they can algorithm their way to billion-dollar drugs.

And yet behind the hype, the world’s biggest drugmakers are recognizing that these tools will be essential for unlocking the next generation of therapies if not remaking the industry altogether.

Regev has been pushing biology in that direction since the earliest days of her career. As an undergraduate at Tel Aviv University, she tried to use natural-language processing— the same technique that lets computers “read” documents or “speak” in a chatbot— to model the circuits that govern how cells function. But she quickly ran into a problem: Biologists didn’t know nearly enough about these circuits to even begin to construct a model.

So, at the direction of a friend, she tried a different tack: allowing the computer to study the system and devise the model for her. Paradoxically, this computer-first approach is how she found herself as the rare computationalist with a wet lab: To prove whether the algorithm’s predictions were correct, she had to perturb the system and see.

Regev went on to run a lab at the Broad Institute, wherein the early 2010s, she says, three innovations changed her work: CRISPR arose, allowing researchers to perturb systems with unprecedented felicity; single-cell sequencing — Regev’s specialty — allowed researchers to generate copious, detailed data; and machine learning, reaching an inflection point, could interpret those data.

In a groundbreaking 2013 paper, she used those systems to individually sequence 18 immune cells, revealing surprising differences between seemingly similar cells. The next year, asked by NIH to pitch an idea for an ambitious but realistic project, she proposed building an atlas of all human cells.

“It was a completely crazy, crazy idea,” geneticist Sarah Teichmann told Endpoints last year. Regev was proposing going from 13 cells to the 37.2 trillion in the human body. “It was completely crazy at that time to think about something like this or anything at this scale.”

And yet two years later, with Teichmann’s help, the project was off the ground. Since then, Regev has helped direct researchers at dozens of labs around the world, while her own work has helped has uncovered hidden secrets about how cystic fibrosis works, how cancer resistance arises, and the basic mechanisms of how all animals develop.

So why leave? “Because,” she told Endpoints last year, “I actually believe the things I say.”

For two decades, Regev argued that more data and more computational power could change how we developed drugs. Now those tools are available and being put to use generating unprecedented insights into human genetics and biology. There were few better places to put them to work than Genentech.

Now, she plans to use machine learning to imagine how drugs are made, from molecule design to clinical trials. She wants to use these tools to predict what happens not if you change one or two genes, as researchers now examine, but if you change three or four — a feat too costly to do by experiment. And she’s already begun enacting that vision, bringing in computational-focused biotech such as Genesis Therapeutics and Dyno Therapeutics.

It’s all part of a brand new vision for how to change human health.

“I wholeheartedly think the inflection point is upon us,” Regev said. “We are not exactly inflected yet, though, and I want to make that inflection happen.”

— Jason Mast

- Highlights AAV vector pioneer, founder of AskBio

Jude Samulski

As one of the pioneers of adeno-associated virus vector research, Jude Samulski has had a decades-long career that has helped spark a boom in the field.

He finished his studies in 1982, getting a PhD from the University of Florida after doing his undergrad work at Clemson University. The use of AAV vectors to deliver a gene stems from a project Samulski worked on as a graduate student after cloning viral DNA into bacterial plasmids.

Samulski now works as the director of the University of North Carolina’s Gene Therapy Center and has founded multiple biotechs over the course of his career. But he’s gained much more prominence recently with his company Asklepios BioPharmaceutical, more commonly known as AskBio, that he launched in tandem with Xiao Xiao, credited with developing the first mini-dystrophin gene.

Though AskBio got started by teaming up on development with Novartis and Pfizer, it burst into a new light with a $235 million megaround back in 2019. The funding came from selling a minority stake in the company to TPG and Vida Ventures for $225 million, as the founders themselves chipped in another $10 million.

The raise came at a time when Big Pharma was taking a closer look at gene therapy technology from the biotech world, following decades of trial and error in the lab. Big companies like Roche, Novartis and Pfizer have been snapping them up over the last few years, and Samulski saw Bayer swoop in for a $4 billion acquisition of AskBio back in late 2020.

That deal included $2 billion in cash and another $2 billion in biobucks, should every milestone be reached. It also left Samulski in charge with seeing that work through to completion, with plenty of industry players watching every step. Bayer’s acquisition came four years after Samulski sold another one of his biotechs — Bamboo Therapeutics — to Pfizer, in a buyout worth up to $645 million. Some of Samulski’s tech work also went into Zolgensma, Novartis’ gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy.

What does the future hold in store for Samulski and AskBio? Perhaps a convergence of gene therapy and neurodegeneration, as the biotech brought over the team from Brain Neurotherapy Bio this past January with a goal to tackle Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. AskBio also hired Spark Therapeutics co-founder Kathy High that same month, helping Bayer continue to push out its gene therapy efforts.

— Max Gelman

- Highlights Former Stanford University professor, Genentech R&D legend, built therapeutic unit at 23andMe

Richard Scheller

When Genentech R&D legend Richard Scheller announced he was retiring back in 2014, 23andMe co-founder Anne Wojcicki reached out within five minutes. Scheller invited her over for a cup of tea — and before the water was boiling, they decided they were going to build a therapeutic unit at 23andMe.

“My background was largely as a molecular biologist or biochemist, and I wanted to learn about human genetics,” Scheller said. “My therapeutic group was sort of like a little biotech company within 23andMe, exclusively using the genetic data that (was) generated by the consumer product.”

Scheller says he can’t remember a time before he wanted to be a scientist. As the curious child of a social worker and hospital administrator, and a stay-at-home mom, Scheller would play with microscopes and chemistry sets. He followed his passion to the University of Wisconsin, where he studied biochemistry. And after graduating in 1975, he went on to pursue a PhD in chemistry at the California Institute of Technology.

In 1981, Scheller set out for the East Coast to study the genes responsible for behavior at Columbia University with Eric Kandel and Richard Axel, both of whom went on to win Nobel Prizes. Scheller had essentially no experience in neuroscience, but he wasn’t going to let that stop him.

“Eric taught me neurobiology, and I taught him molecular biology, which was tremendous fun,” Scheller recalled.

A year later, it was back to the West Coast, where Scheller spent the next 19 years teaching at Stanford. He worked with brilliant students and postdocs, some of whom he still keeps in touch with today. In the late 1980s, Scheller identified several proteins in the synaptic fusion complex (a structure that mediates communication between neurons), and worked with Stanford neuroscientist Thomas Südhof and Yale cell biologist James Rothman to unravel the mechanics of neurotransmission. The work won the trio a 2010 Kavli Prize.

But by 2001, it was time to try something new. He was approached by Genentech, and after meeting with former CEO Art Levinson, he decided the company was as close as he would get to an industry job that felt like academia.

“It was not an easy decision to give up a tenured professorship at Stanford, but I did it,” Scheller said with a chuckle.

He stayed at Genentech for 14 years, serving a five-year stint as CSO and eventually ending as executive vice president of research and early development. At one point, he had around 2,000 people reporting to him. But the most challenging part was his first year or two on the job, because, as he puts it: “I really didn’t know anything about drug discovery, and all of a sudden that’s what I was in charge of doing.”

When Scheller joined 23andMe in 2015, he promised Wojcicki he’d stay four years — and that’s exactly what he did. In that time, the therapeutic unit grew from one to 100, and the team started a handful of projects, one of which is now headed to the clinic in a collaboration with GlaxoSmithKline, where Hal Barron was only too glad to team with a longtime colleague breaking a path in genetics that others are following.

Scheller left the company in 2019 to advise several companies, including 23andMe, Google Ventures, Alector and BridgeBio. He’s also a trustee at Caltech, and the fine art museums of San Francisco.

“I’ve never really felt like I wasn’t working,” the scientist said. “I’ve always felt like I was just doing things that I wanted to do, because they were interesting, and they were fun.”

— Nicole DeFeudis

- Highlights: Longtime Agios CEO, GV partner, developer of two approved cancer drugs

David Schenkein

David Schenkein’s father was a wholesale diamond dealer in New York City, who came to America after fleeing Holland during the Holocaust. That’s where he credits his entrepreneurial streak, he told The Boston Globe in 2018, as his career has gone from helping one patient at a time to thousands, in his transition away from his work as a physician toward pharma.

Right now, Schenkein heads the life-science investment team at GV, in addition to his role as an adjunct professor at Tufts Medical Center, and he has been a hematologist and medical oncologist for the last 30 years. But his claim to fame was growing Agios into a high profile, publicly-traded biotech with 500 employees, two approved drugs and a pipeline filled with potential.

“We’ve gone literally from a blank piece of paper when the company was started, to now having a drug that the FDA has accepted to review the application,” Schenkein told the Boston Business Journal in 2017, when cancer pill enasidenib — now marketed as Idhifa — was accepted for review by the FDA. “That’s obviously very fast.”

A native of Queens, NY, Schenkein graduated from Manhattan’s Stuyvesant High School, then went to Wesleyan University for undergrad, where he majored in chemistry. Then came medical school at the State University of New York’s Upstate Medical University.

Before spending 12 years as a clinical professor of medicine at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, there were stops at Genentech and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. He spent nearly 10 years as the CEO of Agios Pharmaceuticals, where he now sits on the board. In early 2019, he announced that he would leave the company at which he took the helm with just 10 employees in the hands of Jackie Fouse, an ex-Celgene exec.

“It was important to us to make sure we would select someone that would continue the vision,” he said in an interview with Endpoints at the time.

Now, in his VC role at GV, Schenkein backs companies like Encoded Therapeutics, a gene therapy 2.0 focused on breaking through the boundaries of AAV gene therapy in beating Dravet syndrome. He saw the science-heavy approach as a potential game-changer and has morphed into a mentor for the Kartik Ramamoorthi operation.

— Josh Sullivan

- Highlights Built Regeneron from the ground up

George Yancopoulos

The billionaire co-founder of Regeneron has become the LeBron James of the biopharma world, although Yancopoulos’ $130 million pay package in 2020 dwarfed even LeBron’s.

For more than three decades, Yancopoulos has shaped Regeneron into the much-admired industry leader it is today. As CSO, he’s worked at the forefront of all of the company’s groundbreaking science, serving as one of the principal inventors of all eight of its FDA-approved drugs and foundational technologies that have accelerated drug development.

The son of Greek immigrants, Yancopoulos showed promise from an early age as valedictorian of the Bronx High School of Science and as he also won the Westinghouse Science Talent Search, which Regeneron now sponsors. He was valedictorian during his undergrad at Columbia College, where he received his MD and PhD.

While pursuing a career in academia, in 1985, he and his mentor at Columbia, Fred Alt, first proposed making mouse models with genetically human immune systems. Four years later, he and Regeneron co-founder Len Schleifer jumpstarted their company with similar ideas around breeding mice with immune systems that respond just as a human’s would.

It’s had an enormous impact on drug development.

Since then, he has authored more than 300 papers, holds more than 100 patents, and was among the 10 most highly cited scientific authors in the world during the 1990s, and the only one in industry on the list.

He was also elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2004, inducted into the Biotech Hall of Fame in 2014, and was named Ernst & Young’s Entrepreneur of the Year in 2016 (along with Schleifer), among other awards and honors.

When people in the industry today set out to become “the next Regeneron,” it’s the tough-talking Yancopoulos — perhaps the best paid R&D chief in biopharma history — they would most like to be in life.

— Zachary Brennan

depression pandemic coronavirus covid-19 nasdaq stocks vaccine treatment testing fda clinical trials preclinical genome genetic antibodies therapy rna dna gold oil europe germany hungary chinaGovernment

When Military Rule Supplants Democracy

When Military Rule Supplants Democracy

Authored by Robert Malone via The Brownstone Institute,

If you wish to understand how democracy ended…

Authored by Robert Malone via The Brownstone Institute,

If you wish to understand how democracy ended in the United States and the European Union, please watch this interview with Tucker Carlson and Mike Benz. It is full of the most stunning revelations that I have heard in a very long time.

The national security state is the main driver of censorship and election interference in the United States.

“What I’m describing is military rule,” says Mike Benz.

“It’s the inversion of democracy.”

Please watch below...

Ep. 75 The national security state is the main driver of censorship and election interference in the United States. "What I’m describing is military rule," says Mike Benz. "It’s the inversion of democracy." pic.twitter.com/hDTEjAf89T

— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) February 16, 2024

I have also included a transcript of the above interview. In the interests of time – this is AI generated. So, there still could be little glitches – I will continue to clean up the text over the next day or two.

Note: Tucker (who I consider a friend) has given me permission to directly upload the video above and transcript below – he wrote this morning in response to my request:

Oh gosh, I hope you will. It’s important.

Honestly, it is critical that this video be seen by as many people as possible. So, please share this video interview and transcript.

Five points to consider that you might overlook;

First– the Aspen Institute planning which is described herein reminds me of the Event 201 planning for COVID.

Second– reading the comments to Tucker’s original post on “X” with this interview, I am struck by the parallels between the efforts to delegitimize me and the new efforts to delegitimize Mike Benz. People should be aware that this type of delegitimization tactic is a common response by those behind the propaganda to anyone who reveals their tactics and strategies. The core of this tactic is to cast doubt about whether the person in question is unreliable or a sort of double agent (controlled opposition).

Third– Mike Benz mostly focuses on the censorship aspect of all of this, and does not really dive deeply into the active propaganda promotion (PsyWar) aspect.

Fourth– Mike speaks of the influence mapping and natural language processing tools being deployed, but does not describe the “Behavior Matrix” tool kit involving extraction and mapping of emotion. If you want to dive in a bit further into this, I covered this latter part October 2022 in a substack essay titled “Twitter is a weapon, not a business”.

Fifth– what Mike Benz is describing is functionally a silent coup by the US Military and the Deep State. And yes, Barack Obama’s fingerprints are all over this.

Yet another “conspiracy theory” is now being validated.

Transcript of the video:

Tucker Carlson:

The defining fact of the United States is freedom of speech. To the extent this country is actually exceptional, it’s because we have the first amendment in the Bill of Rights. We have freedom of conscience. We can say what we really think.

There’s no hate speech exception to that just because you hate what somebody else thinks. You cannot force that person to be quiet because we’re citizens, not slaves. But that right, that foundational right that makes this country what it is, that right from which all of the rights flow is going away at high speed in the face of censorship. Now, modern censorship, there’s no resemblance to previous censorship regimes in previous countries and previous eras. Our censorship is affected on the basis of fights against disinformation and malformation. And the key thing to know about this is that they’re everywhere. And of course, this censorship has no reference at all to whether what you’re saying is true or not.

In other words, you can say something that is factually accurate and consistent with your own conscience. And in previous versions of America, you had an absolute right to say those things. but now – because someone doesn’t like them or because they’re inconvenient to whatever plan the people in power have, they can be denounced as disinformation and you could be stripped of your right to express them either in person or online. In fact, expressing these things can become a criminal act and is it’s important to know, by the way, that this is not just the private sector doing this.

These efforts are being directed by the US government, which you pay for and at least theoretically owned. It’s your government, but they’re stripping your rights at very high speed. Most people understand this intuitively, but they don’t know how it happens. How does censorship happen? What are the mechanics of it?

Mike Benz is, we can say with some confidence, the expert in the world on how this happens. Mike Benz had the cyber portfolio at the State Department. He’s now executive director of Foundation for Freedom Online, and we’re going to have a conversation with him about a very specific kind of censorship. By the way, we can’t recommend strongly enough, if you want to know how this happens, Mike Benz is the man to read.

But today we just want to talk about a specific kind of censorship and that censorship that emanates from the fabled military industrial complex, from our defense industry and the foreign policy establishment in Washington. That’s significant now because we’re on the cusp of a global war, and so you can expect censorship to increase dramatically. And so with that, here is Mike Benz, executive director of Foundation for Freedom online. Mike, thanks so much for joining us and I just can’t overstate to our audience how exhaustive and comprehensive your knowledge is on this topic. It’s almost unbelievable. And so if you could just walk us through how the foreign policy establishment and defense contractors and DOD and just the whole cluster, the constellation of defense related publicly funded institutions, stripped from us,

Mike Benz: