International

Follies in the History of Economic Thought

A Book Review of Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom through the Ages, by Michael Keen and Joel Slemrod.1

Introduction

What do you…

- A Book Review of Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom through the Ages, by Michael Keen and Joel Slemrod.1

Introduction

Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom through the Ages by Michael Keen and Joel Slemrod delivers a book on taxation that is part history, part primer, and full of surprises—even for those familiar with both topics. The few missteps don’t detract too much from their larger success, although this reviewer certainly hopes they are corrected in future work.

The Window Tax

I’ll start, as the authors do, with the “window tax.” For the many of you already familiar with this, feel free to skip the rest of this paragraph. It’s a well-known and often used example in writings about strange taxes. Even today, you can find pictures of homes with boarded up windows in London, a century and half after the tax was ended.

The window tax existed in Britain from 1697 to 1851. It is exactly what it sounds like: a tax on property based on the number of windows that it had (though with different rates depending on the number of windows, see below).

Keen and Slemrod use this example to illustrate the conflict and tradeoff between different tax principles like fairness, ease of administration, and their favorite, the excess burden (the non-revenue costs of the tax, when people change their behavior in ways that make them worse off).

Fairness: From a fairness perspective, the window tax seems like a good one. In general, richer people will have bigger houses, which will have more windows, so the window tax could be a way of implementing a progressive tax, consistent with the ability-to-pay principle (which says that those with a great ability to pay taxes should pay more). This fact may not always hold though, as Adam Smith keenly observed (see below).

Ease of Administration: Prior to the window tax, Britain had a tax on fireplaces (the “hearth tax”), which was in place from 1662 to 1689. Compared with the later window tax, the hearth tax was difficult to administer, since the number of fireplaces in a house could not be easily observed from outside the home. You had to enter the home, which, not surprisingly, many Brits found intrusive. Relatively speaking, the window tax was easier to administer, as it could be observed without entering the home (and without trying to assess the market value of the home, as with a property tax). The tax assessor can just count the windows, and move on to the next house.

Excess Burden: But there is also the potential for a huge excess burden from the tax. If households respond to the tax by boarding up windows, or if new homes built have fewer windows, people are worse off. They don’t have to pay the tax, true, but they also miss out on the benefits of the sunshine that would otherwise stream through their windows. Economists call this loss of benefits a “deadweight loss,” or more precisely in the context of taxation, what we call the “excess burden.”

Adam Smith, Prominent “Window Tax” Critic: As Keen and Slemrod note, Adam Smith complained about the window tax in the Wealth of Nations.2 Specifically, Smith said it was unfair, even though progressivity was one of the goals. Smith gives the example of a poor person living in the country, compared with a rich person in an urban area. The poor person might actually have a house with more windows, given how cheap land is in rural areas, and thus will shoulder a larger burden of the tax. Perhaps it wasn’t such a fair tax after all.

But What Happened? Here is where this book really shines. The authors not only know the history of taxes, they are also well-versed in the best current research on taxes.

On the window tax, they do an excellent job of summarizing research published in 2015 that examined microdata on the window tax.3 Initially, the window tax didn’t apply to dwellings with fewer than ten windows. Guess what the microdata Oates and Schwab examined shows? Lots of houses with exactly nine windows. Whether this means new houses were built with exactly nine windows, or whether houses with ten or eleven windows boarded up a few, we can’t say from the data. Moreover, when the threshold for taxation was lowered to eight windows in 1761, suddenly there were a lot of houses with exactly seven windows.

The “excess burden” of the tax is implicit in the shrinking number of windows in these houses. The authors found that for every dollar of taxes collected from the tax, there was an excess burden of 23 cents, a very inefficient tax. And for those who reduced their number of windows below the exemption threshold, all their behavior is excess burden, since the tax raises no revenue on those with nine windows (in the original version of the tax).

The story Keen and Slemrod tell of the window tax is well done in that it takes a familiar tale of tax lore, talks clearly about the incentives to change behavior under the tax, and then shows us what the best current research says about this tax, which we can then use to compare with other taxes.

Follies in the History of Economic Thought

The authors gave their book the subtitle “tax follies and wisdom throughout the ages,” but they do commit a few follis of their own. These follies do not detract from the book overall, but they are so glaring that they need to be briefly corrected.

Keen and Slemrod’s discussion of the history of economic thought goes astray when they say that Thomas Robert Malthus’s “views of population dynamics prompted Thomas Carlyle to label economics as the ‘dismal science'” (page 155). This is the standard story, often repeated by critics of economics, but economists should know their own history better. As David Levy and Sandra Peart have carefully explained, Carlyle called economics “the dismal science” because “economics assumed that people were basically all the same, and thus all entitled to liberty.”4 Carlyle and other progressives argued in favor of a racial hierarchy and questioned the abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

The authors also do an injustice to more recent history of economic thought in their discussion of Geoffrey Brennan and James Buchanan’s work on taxation. According to Keen and Slemrod, Brennan and Buchanan “thought of government as a ‘leviathan’ (a biblical sea monster) concerned not with citizens’ welfare but only with maximizing its own size.” In this context, Leviathan is clearly a reference to Hobbes, and surely the authors know this. Most uncharitably, for a reader interested in learning about Brennan and Buchanan’s theory, the authors give no references to the relevant papers in the Journal of Public Economics and later book The Power to Tax.5 After quickly dismissing the leviathan model, Keen and Slemrod go on in the next paragraph to say, “An alternative way to limit government size… is through constitutional restrictions.” But this is exactly what Brennan and Buchanan propose, as would be clear by just reading the title of their 1977 paper “Towards a tax constitution for Leviathan.”6

What’s Next for Taxes?

In the final chapter of the book, Keen and Slemrod look to the future. Given all the history they have shared with us, what might future tax changes look like? What should they look like?

As the authors acknowledge, good tax reform is hard. They quote United States Treasury Secretary William Simons saying in the late 1970s that the United States “should have a tax system which looks like someone designed it on purpose.” This sentiment is nice, but it’s not realistic. Even major tax reforms in the United States, such as in 1986, didn’t truly start over from scratch and design a tax system of which economists would approve. Instead, tax reforms usually try to chip away at bad tax policy, often add new (hopefully better, by some criteria) revenue raising devices, but most tax changes take place at the margin. A rate adjustment here, and an exemption added or subtracted there. Taxes are the outcome of an outgoing political debate and negotiation, not some that is designed fresh from whole cloth.

For example, it’s widely acknowledged in tax policy discussions that the United States is a tax outlier in two clear ways compared to other developed countries. First, we don’t have a value-added tax, a fairly new taxing device in the history of taxation, but one that is now universally adopted in the developed world, and much of the developing world too. In brief, a value-added tax (VAT) is a tax on consumption, but it works very differently from a sales tax, with taxes collected at each stage in the production process (only on the “value added” at each stage, hence the name). Second, the United States generally has much lower taxes as a percent of our national economy than our peers. These two facts are related: with a VAT, the United States would be much closer to, say, the average level of taxation in Europe.

Will the United States have a VAT in the near future? The authors do think it’s plausible, especially since recent Republican (Ron Paul and Ted Cruz in 2016) and Democratic (Andrew Yang in 2020) presidential candidates have proposed VAT-like taxes, even if they didn’t always call it that. But whether it will be a replacement for an existing tax (the Republicans’ preferred path) or a new revenue stream to fund new programs (the Democratic preference), it will inevitably be messy and uniquely American. For example, how would the VAT interact with our existing large consumption tax in the United States: the state and local retail sales tax? Would it tax the same “base” of consumer goods (warning: every state has a different tax base for its retail sales tax)? Would the retail sales tax be applied on top of the federal VAT, since the VAT is baked into the price of the goods on the shelf?

The possibility of a VAT in the United States demonstrates that reform is possible, but it is almost always likely to be more incremental than revolutionary. And major expansions of taxation in the United States and elsewhere usually require a war or some other crisis. For example, while the United States federal income tax was established during peacetime, the rates were lower until a few years later when the United States entered World War I, and it only became a tax that applied to most households during World War II. Similarly, the payroll tax in the United States was established to fund the Social Security program during the crisis of the Great Depression. The fact that we’ve mostly gotten through the COVID pandemic without any new major tax instruments at the federal level suggests that the moment for a major new tax may have passed in the United States.

To Conclude, a Personal Anecdote

Twenty years ago as an undergraduate student, I saw Joel Slemrod give two public lectures at my university. These two lectures nicely encapsulated two of the main objectives of Slemrod’s recent book with Michael Keen, titled Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue. First, how do taxes impact people’s behavior and, second, how can taxes be made simpler, fairer, and more efficient?

The first talk by Slemrod was based on his paper with Wojciech Kopczuk, which investigated whether or not people responded to changes in estate tax rates by dying earlier or later (for example, the United States estate tax was temporarily repealed in 2010).7 In the case of estate taxes, they do find some adjustment of behavior—the alteration of death dates close to the end of the year. That’s the first lesson of their book: taxes change people’s behavior, they don’t just raise revenue.

The second of Slemrod’s talks I witnessed was “Which is the Simplest Federal Tax System of Them All?” In that talk Slemrod discussed various options for tax reform, such as consumption taxes, a flat income tax, and others. Here we have the second major theme of the book: how can we reform the tax system, including ways to make it simpler, but also ways to make it “fairer” (and what that means exactly), and finally how to make the tax system more efficient.

For more on these topics, see

- Taxation, by Joseph J. Minarik. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

- Fiscal Policy, by David N. Weil. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

- Tammy Frisby on Tax Reform. EconTalk.

- Vanessa Williamson on Taxes and Read My Lips. EconTalk.

The authors are humble throughout the book, as they never try to claim they have “the” answer to how to fix our tax system. As one of the section titles in the last chapter of the book puts it: “Fair Taxation, Whatever That Is, Is Hard to Achieve.” This stance is a refreshing one, since most authors that set out to write a 400-page book on taxes would usually have One Big Idea about how to fix the tax system. Not Keen and Slemrod. They are content to give us an interesting history, connect it to principles of taxation, and offer some suggestions, but they leave it up to the reader to make use of all this information in shaping their own ideas about the future of taxes in the modern world.

Footnotes

[1] Michael Keen and Joel Slemrod, Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom through the Ages. Princeton University Press, 2021.

[2] Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Book V, Chapter 2, “Of the Source of the General or Public Revenue of the Society.” Library of Economics and Liberty

[3] Wallace E. Oates and Robert M. Schwab, “The Window Tax: A Case Study in Excess Burden.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(1), 2015.

[4] David Levy and Sandra Peart, “The Secret History of the Dismal Science: Economics, Religion, and Race in the 19th Century.” Library of Economics and Liberty, January 22, 2001.

[5] Geoffrey Brennan and James Buchanan, The Power to Tax. Library of Economics and Liberty.

[6] Geoffrey Brennan and James Buchanan, “Towards a tax constitution for Leviathan.” Journal of Public Economics. 8(3), 1977.

[7] Wojciech Kopczuk and Joel Slemrod, “Dying to Save Taxes: Evidence from Estate Tax Returns on the Death Elasticity.” The Review of Economics and Statistics. 85(2), 2003.

*Jeremy Horpedahl is Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Central Arkansas. He blogs at Economist Writing Every Day.

As an Amazon Associate, Econlib earns from qualifying purchases.

Government

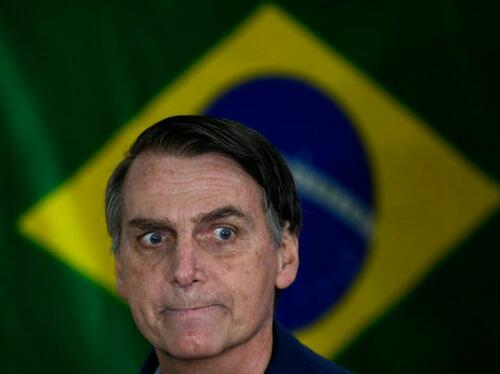

Bolsonaro Indicted By Brazilian Police For Falsifying Covid-19 Vaccine Records

Bolsonaro Indicted By Brazilian Police For Falsifying Covid-19 Vaccine Records

Federal police in Brazil have indicted former President Jair…

Federal police in Brazil have indicted former President Jair Bolsonaro for falsifying his Covid-19 vaccine card in order to travel to the United States and elsewhere during the pandemic.

Federal prosecutors will review the indictment and decide whether to pursue the case - which would be the first time the former president has faced criminal charges.

According to the indictment, Bolsonaro ordered a top deputy to obtain falsified Covid-19 vaccine records of himself and his 13-year-old daughter in late 2022, right before he flew to Florida for a three-month stay following his election loss.

Brazilian police are also waiting to hear back from the US DOJ on whether Bolsonaro used said cards to enter the United States, which would open him up to further criminal charges, the NY Times reports.

Bolsonaro has repeatedly claimed not to have received the Covid-19 vaccine, but denies any involvement in a plan to falsify his vaccination records. A previous investigation by Brazil's comptroller general concluded that Bolsonaro's vaccination records were false.

The records show that Bolsonaro, a COVID-19 skeptic who publicly opposed the vaccine, received a dose of the immunizer in a public healthcare center in Sao Paulo in July 2021. [ZH: hilarious, Reuters calling the vaccine an 'immunizer.']

The investigation concluded, however, that the former president had left the city the previous day and didn't leave Brasilia until three days later, according to a statement.

The nurse listed in the records as having applied the vaccine on Bolsonaro denied doing so and was no longer working at the center. The listed vaccine lot was also not available on that date, the comptroller general's office said. -Reuters

"It's a selective investigation. I'm calm, I don't owe anything," Bolsonaro told Reuters. "The world knows that I didn't take the vaccine."

During the pandemic, Bolsonaro panned the vaccine - and instead insisted on alternative treatments such as Ivermectin, which has antiviral properties against Covid-19. For this, he was investigated by Brazil's congress, which recommended that the former president be charged with "crimes against humanity," among other things, for his actions during the pandemic.

In May, Brazilian police raided Bolsonaro's home, confiscating his cell phone and arresting one of his closest aides and two of his security cards in connection to the vaccine record investigation.

Brazil's electoral court ruled that Bolsonaro can't run for public office until 2030 after he suggested that the country's voting system was rigged. For that, he has to sit out the 2026 election.

International

This gambling tech stock is future-proofing the world’s casinos

Supported by the universal thrill of a quick payout and the need for leisure, gambling stocks make a compelling case for long-term returns.

The post This…

Supported by the universal human thrill of a quick payout, and the need for leisure and entertainment to bring enjoyment to adult life, casinos will remain essential spaces for people to dream and play for the foreseeable future, making gambling stocks a prospective space to look for long-term returns.

According to Research and Markets, the global casino industry was valued at US$157.5 billion in 2022, and it will grow to US$224.1 billion by 2030 at a compound annual growth rate of 4.5 per cent. This trend includes:

Approximately 100 million gamblers in the United States, who generated US$66.5 billion in revenue in 2023, a 10 per cent gain from 2022, which itself was a record year A little fewer than 20 million gamblers in Canada, who generated about C$15 billion in revenue in 2023 A global addressable market of thousands of casinos, and more than 4.2 billion people who gamble at least once every year, according to a 2016 study by Casino.orgThe main challenge with attracting these billions through casino doors is they sway heavily toward middle age. The mean age of U.S. casino visitors has hovered around 50 for the past decade, with a similar trend across the world, forcing casinos to attract younger, tech-savvy customers, many with less gambling experience, to continue growing profits for their stakeholders over the long term.

Investors seeking exposure to a leadership position in building the bridge between casinos and the next generation of gamblers should evaluate Jackpot Digital (TSXV:JJ). The Vancouver-based company is a manufacturer of dealerless electronic table games that deliver immersive experiences tailored to the digital age, while earning casinos attractive returns on investment.

The gambling technology stock benefits from no direct competition in the dealerless poker space, with orders spanning North America, Europe, Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, a long-established presence with major cruise ship brands, such as Carnival, Princess Cruises and Holland America, and a growing land-based presence with orders or ongoing installations across 12 U.S. states. Its highlight partnership to date is a master services agreement with Penn Entertainment, the country’s largest regional gaming operator with 43 properties across 20 states.

Jackpot Digital’s differentiated technology and well-rounded management team are at the heart of its success in landing several blue-chip casino gaming companies as customers.

Jackpot BlitzThe gambling technology stock’s flagship product, Jackpot Blitz, is a dealerless poker table featuring three of the world’s most popular variations – Texas Hold’ em, Omaha, and Five-Card-Omaha – brought to life through slick 4k graphics on a 75-inch touchscreen, and offered in three formats – pot-limit, no-limit and fixed-limit – designed to attract a diversity of revenue from casual to experienced players.

Spokesperson and NFL championship-winning coach Jimmy Johnson explains the benefits of the Jackpot Blitz. Source: Jackpot Digital.The table also comes equipped with house-banked mini-games, including blackjack, baccarat and video poker, as well as side bets on the main poker game, such as Bet the Flop, all of which keep players engaged and entertained between, and even during, poker hands. The stunning Jackpot Blitz machine also offers multi-venue “Bad Beat” jackpot functionality, allowing casinos to offer a “Poker Powerball” with massive Jackpots, further enhancing the attractiveness of Jackpot Blitz to new players.

It’s by striking a balance between the needs of the modern gambler, and efficiency and profitability that in-person operators couldn’t hope to match – unless they ordered the machine for themselves – that Jackpot Digital has earned itself the top spot in dealerless poker.

Player benefitsWhen a veteran or novice gambler takes a seat at the Jackpot Blitz, his or her experience begins with an easy-to-use interface, laid out in a modern and stylish design, programmed to respond to hand gestures that bring real casino play into the digital age, including card bending and chip jingling.

Source: Jackpot Digital.The table’s intuitive controls, combined with instant payouts and its dealerless nature, translate into faster game play, which maximizes playing time and player excitement, while minimizing human error and the intimidation new gamblers might feel about approaching an analog poker table. The gambling technology stock’s in-house development team is also constantly working on new games to keep content fresh, with a special focus on bringing international games and regional versions of poker to casino audiences in Asia, South America and the Indian subcontinent.

As hands are laid down and pots pile up, players can also track game stats in real time, which inform future strategy and enhance the thrill of the moment with an added element of competition.

Operator benefitsFrom an operator’s perspective, a floor of automated gaming tables can meaningfully and instantly reduce casino staff expenditures and management pain points, while avoiding wage inflation, labour shortages and supply costs.

The Blitz is no slouch on revenue either, dealing more hands per hour, resulting in higher revenue and higher profitability, which is further enhanced by onboard side bets and mini-games that can be played while players are engaged in a poker hand.

The Jackpot Blitz’s economics are attractive to operators thanks to its ability to accommodate non-stop play, while monetizing downtime through side games and bets. While a human dealer must spend time shuffling, interacting with players, and consulting with colleagues, the Jackpot Blitz can accept wagers 100 per cent of the time, making sure gamblers get the action they came for and operators see a return on their investment.

Source: Jackpot Digital.

Source: Jackpot Digital.

Beyond gaming revenue, casinos are further incentivized to onboard the Jackpot Blitz because of its fully customizable advertising functions, including logos, card backs, chips and felt colors, all of which bolster casino culture and enable the pursuit of revenue from third-party advertising partners.

The Blitz ties its value proposition together by generating automatic reports – including demographics and consumer behaviour through a rewards card system – and plugging directly into most back-end management systems, saving casinos the hassle of manual tracking, while also minimizing tampering, money-laundering and theft through the use of isolated servers.

Whether it’s streamlining the player experience or putting automation at the service of operators’ bottom lines, Jackpot Digital’s flagship product is positioned to create value, and plenty of it.

Jackpot Digital’s path to profitabilityAfter existing as an exclusively cruise-ship-based operation since 2015, Jackpot Digital suffered a steep decline in revenue during the COVID pandemic, falling from C$2.18 million in 2019 to C$0.42 million in 2021.

Management quickly pivoted in the face of uncertainty, redesigning the Blitz to execute on a land-based expansion strategy – backed by Gaming Labs International certification in fall 2023 – which is bringing about a successful turnaround after the re-emergence of the casino business. Revenue more than tripled to C$1.43 million in 2022, and reached C$1.57 million through three quarters of 2023, with the company expecting to ramp up significant recurring revenue after it installs several dozen machines currently in its backlog.

The Jackpot Blitz electronic gaming table in action. Source: Jackpot Digital.

The Jackpot Blitz electronic gaming table in action. Source: Jackpot Digital.

The first installation of land-ready Jackpot Blitz machines is now completed at the Jackson Rancheria Casino in California, as the company announced today. The three-machine installation marks a new era of growth for the company, having announced 25 Blitz deals since November 2021 (slide 12), with many more across Canada and the United States in the works, in addition to a strong pipeline in Asia and Europe.

“Jackpot Digital could be a profitable company right now if it only focused on care and maintenance of the revenues it currently generates. But that’s not why we’re here,” Mathieu McDonald, Vice President of Corporate Development at Jackpot Digital, said in a recent interview with Stockhouse. “We intend to scale up to many multiples of the tables we have out right now, with the potential for up to 2,000 tables over the next three to five years.”

According to McDonald, the company is fielding three to five inquiries per week about the Blitz from casinos around the world that recognize the machines’ first-mover advantage in dealerless poker and potential expansion into other games in need of automation.

Jackpot Digital’s ambitious plan of action is supported by a management team of proven gambling, finance, advertising and legal professionals, many of which have been serving Jackpot stakeholders for more than two decades.

A long-tenured management teamThe management team behind Jackpot Digital is led by Jake Kalpakian, who has served as president and chief executive officer since 1999, including under the gambling technology stock’s former incarnation as Las Vegas From Home.com Entertainment Inc. Kalpakian brings more than 30 years of experience managing small-cap publicly listed companies, granting him a steady hand when it comes to maneuvering through the volatility of the economic cycle.

Kalpakian’s efforts are supported by three directors whose well-rounded expertise positions Jackpot Digital for long-term sustainable growth:

Gregory T. McFarlane, a director at Jackpot Digital since 1999, previously ran an independent advertising firm and holds a degree in mathematics from the University of Toronto. McFarlane is also a co-founder of the popular Control Your Cash personal finance website. Chief financial officer Neil Spellman, a director at the company since 2002, boasts an almost two-decade track record as vice president at Wall Street firm Smith Barney, where he developed a multi-industry understanding of the journey to profitability. Finally, Alan Artunian, a director since 2017, currently serves as CEO of Nice Guy Holdings, a corporate and legal consulting company advising clients across a diversity of sectors.Guided by a strategic management team, and benefiting from a macro-trend toward casino automation, Jackpot Digital is on course to ride a wave of millions of gamblers looking for an elegant, tech-informed alternative to traditional in-person play.

A multi-bagger opportunityThe Jackpot Digital opportunity sets up savvy investors who recognize the soundness of the company’s value proposition. The tremendous risk/reward value of Jackpot Digital gives investors the opportunity to ride the macro-trend toward casino automation, as deals for the Blitz keep pouring in, the company adds games to its portfolio, and the global casino industry adds hundreds of billions in revenue through this decade.

Join the discussion: Find out what everybody’s saying about this gambling technology stock on the Jackpot Digital Bullboard.

This is sponsored content issued on behalf of Jackpot Digital, please see full disclaimer here.

The post This gambling tech stock is future-proofing the world’s casinos appeared first on The Market Online Canada.

stocks pandemic small-cap africa south america canada europeInternational

Gates-backed PhIII study tuberculosis vaccine study gets underway

A large study of an experimental vaccine for the world’s biggest infectious disease has finally kicked off in South Africa.

The Bill & Melinda Gates…

A large study of an experimental vaccine for the world’s biggest infectious disease has finally kicked off in South Africa.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute (MRI) will test a tuberculosis vaccine’s ability to prevent latent infections from causing potentially deadly lung disease. Last summer the nonprofit said it would foot $400 million of the estimated $550 million cost of running the 20,000-person Phase III trial.

It’s a pivotal moment for a vaccine whose origins date back 25 years when scientists identified two proteins that triggered strong immunity to the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. A fusion of those proteins, paired with the tree bark-derived adjuvant that helps power GSK’s shingles shot, comprise the so-called M72 vaccine.

After decades of failures in the field, the vaccine impressed scientists in 2018 when GSK found that it was 54% efficacious at preventing lung disease in a 3,600-person Phase IIb study.

But the Big Pharma decided that a full-blown trial was too expensive to conduct on its own. Gates MRI stepped in to license the vaccine in early 2020, right before the Covid pandemic shifted global vaccine priorities towards the coronavirus, further stalling the tuberculosis shot.

“There’s been frustration that it’s taken so long to get this trial up and running,” Thomas Scriba, deputy director of immunology for the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative, told Endpoints News last summer.

At last, the vaccine is getting a chance to prove itself in a bigger study. If successful, it could lead to the first new shot for tuberculosis in over a century.

Emilio Emini, CEO of the Gates MRI, told Endpoints that the initial results may come in roughly four to six years. “Hopefully this will galvanize a refocus on TB,” he said. “It’s been ignored for many, many years. We can’t ignore it anymore.”

A substantial impact

Even though an existing vaccine helps protect babies and children against severe tuberculosis, the bacterium responsible for the disease still causes roughly 10 million new cases and 500,000 deaths each year.

Emilio Emini

Emilio EminiBy vaccinating adolescents and adults who test positive for infections but don’t have symptoms of lung disease, the Gates MRI hopes the shot will help prevent mild infections from becoming severe ones, curtail transmission of the bug, which is predominantly driven by people with lung disease, and reduce deaths.

“The impact would be substantial,” Emini said. But he cautioned that the biology behind mild and severe diseases is still mysterious. “The reality is that no one really knows what keeps it under control.”

The study, which will take place at 60 sites across seven countries, will include some people who are not infected with tuberculosis to ensure that the vaccine is safe in that broader population.

“Having to pre-test everybody is not going to make the vaccine easy to deliver,” Emini said. If the vaccine is ultimately approved, it will likely be used in targeted communities with high tuberculosis, rather than across a whole country, he added. “In practice, you would immunize everybody in those populations.”

Emini described the Gates MRI’s rights to the vaccine as “close to a worldwide license.” GSK retained rights to commercialize the vaccine in certain countries but declined to specify which ones.

A spokesperson for GSK said that the company “has around 30 assets under development specifically for global health … none of which are expected to generate significant return on investment.”

“It is not sustainable or practical in the longer term for GSK to deliver all of these alone. So we continue to work on M72, but in partnership with others,” the spokesperson added.

If the shot works, Emini said that the Gates MRI will sublicense it to a manufacturer that will be responsible for making and marketing the vaccine. The details are still being worked out, he noted.

vaccine pandemic coronavirus deaths new cases transmission africa-

Spread & Containment7 days ago

Spread & Containment7 days agoIFM’s Hat Trick and Reflections On Option-To-Buy M&A

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International2 weeks ago

International2 weeks agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex