Government

Fed’s Waller Drops Bombshell: ‘Climate Change Risks Not Material To US’

Fed’s Waller Drops Bombshell: ‘Climate Change Risks Not Material To US’

This will not go down well with the climate alarmists and ESG grifters…

No…

This will not go down well with the climate alarmists and ESG grifters...

No lesser mortal than Fed Governor Christopher Waller has dared to proclaim that climate change does not pose such "significantly unique or material" financial stability risks that the Federal Reserve should treat it separately in its supervision of the financial system.

"Climate change is real, but I do not believe it poses a serious risk to the safety and soundness of large banks or the financial stability of the United States," Waller said in remarks prepared for delivery to an economic conference in Spain.

"Risks are risks ... My job is to make sure that the financial system is resilient to a range of risks. And I believe risks posed by climate change are not sufficiently unique or material to merit special treatment."

His comments echo Chair Powell's more conservative attitude towards The Fed's responsibility for climate issues than its counterparts in Europe, who previously said that the U.S. central bank was not a climate policymaker and would not steer capital or investment away from the fossil fuel industry, for example.

So presumably this means The Fed does not believe the world will end within a decade in a devastating flood and fireball?

Read Waller's full (carefully and diplomatically worded) statement below: (emphasis ours)

Climate change is real, but I do not believe it poses a serious risk to the safety and soundness of large banks or the financial stability of the United States. Risks are risks. There is no need for us to focus on one set of risks in a way that crowds out our focus on others. My job is to make sure that the financial system is resilient to a range of risks. And I believe risks posed by climate change are not sufficiently unique or material to merit special treatment relative to others. Nevertheless, I think it's important to continue doing high-quality academic research regarding the role that climate plays in economic outcomes, such as the work presented at today's conference.

In what follows, I want to be careful not to conflate my views on climate change itself with my views on how we should deal with financial risks associated with climate change. I believe the scientific community has rigorously established that our climate is changing. But my role is not to be a climate policymaker. Consistent with the Fed's mandates, I must focus on financial risks, and the questions I'm exploring today are about whether the financial risks associated with climate change are different enough from other financial stability risks to merit special treatment. But before getting to those questions, I'd like to briefly explain how we think about financial stability at the Federal Reserve.

Financial stability is at the core of the Federal Reserve and our mission. The Federal Reserve was created in 1913, following the Banking Panic of 1907, with the goal of promoting financial stability and avoiding banking panics. Responsibilities have evolved over the years. In the aftermath of the 2007-09 financial crisis, Congress assigned the Fed additional responsibilities related to promoting financial stability, and the Board of Governors significantly increased the resources dedicated to that purpose. Events in recent years, including the pandemic, emerging geopolitical risks, and recent stress in the banking sector have only highlighted the important role central banks have in understanding and addressing financial stability risks. The Federal Reserve's goal in financial stability is to help ensure that financial institutions and financial markets remain able to provide critical services to households and businesses so that they can continue to support a well-functioning economy through the business cycle.

Much of how we think about and monitor financial stability at the Federal Reserve is informed by our understanding of how shocks can propagate across financial markets and affect the economy. Economists have studied the role of debt in the macroeconomy dating all the way back to Irving Fisher in the 1930s, and in the past 40 years it has been well established that financial disruptions can reduce the efficiency of credit allocation and have real effects on the broader economy. When borrowers' financial conditions deteriorate, lenders tend to charge higher rates on loans. That, in turn, can lead to less overall lending and negatively affect the broader economy. And in the wake of the 2007-09 financial crisis, we've learned more about the important roles credit growth and asset price growth play in "boom-bust" cycles.

Fundamentally, financial stress emerges when someone is owed something and doesn't get paid back or becomes worried they won't be paid back. If I take out a loan from you and can't repay it, you take a loss. Similarly, if I take out a mortgage from a bank and I can't repay it, the bank could take a loss. And if the bank hasn't built sufficient ability to absorb those losses, it may not be able to pay its depositors back. These dynamics can have knock-on effects on asset prices. For example, when people default on their home mortgage loans, banks foreclose and seek to sell the homes, often at steep discounts. Those foreclosure sales can have contagion effects on nearby house prices. When a lot of households and businesses take such losses around the same time, it can have real effects on the economy as consumption and investment spending take a hit and overall trust in financial institutions wanes. The same process works when market participants fear they won't be paid back or be able to sell their assets. Those fears themselves can drive instability.

The implication is that risks to financial stability have a couple of features. First, the risks must have relatively near-term effects, such that the risk manifesting could result in outstanding contracts being breached. Second, the risks must be material enough to create losses large enough to affect the real economy.

These insights about vulnerabilities across the financial system inform how we think about monitoring financial stability at the Federal Reserve. We identify risks and prioritize resources around those that are most threatening to the U.S. financial system. We distinguish between shocks, which are inherently difficult to predict, and vulnerabilities of the financial system, which can be monitored through the ebb and flow of the economic cycle. If you think about it, there is a huge set of shocks that could hit at any given time. Some of those shocks do hit, but most do not. Our approach promotes general resiliency, recognizing that we can't predict, prioritize, and tailor specific policy around each and every shock that could occur.

Instead, we focus on monitoring broad groups of vulnerabilities, such as overvalued assets, liquidity risk in the financial system, and the amount of debt held by households and businesses, including banks. This approach implies that we are somewhat agnostic to the particular sources of shocks that may hit the economy at any point in time. Risks are risks, and from a policymaking perspective, the source of a particular shock isn't as important as building a financial system that is resilient to the range of risks we face. For example, it is plausible that shocks could stem from things ranging from increasing dependence on computer systems and digital technologies to a shrinking labor force to geopolitical risk. Our focus on fundamental vulnerabilities like asset overvaluation, excessive leverage, and liquidity risk in part reflects our humility about our ability to identify the probabilities of each and every potential shock to our system in real time.

Let me provide a tangible example from our capital stress test for the largest banks. We use that stress test to ensure banks have sufficient capital to withstand the types of severe credit-driven recessions we've experienced in the United States since World War II. We use a design framework for the hypothetical scenarios that results in sharp declines in asset prices coupled with a steep rise in the unemployment rate, but we don't detail the specific shocks that cause the recession because it isn't necessary. What is important is that banks have enough capital to absorb losses associated with those highly adverse conditions. And the losses implied by a scenario like that are huge: last year's scenario resulted in hypothetical losses of more than $600 billion for the largest banks. This resulted in a decline in their aggregate common equity capital ratio from 12.4 percent to 9.7 percent, which is still more than double the minimum requirement.

That brings us back to my original question: Are the financial risks stemming from climate change somehow different or more material such that we should give them special treatment? Or should our focus remain on monitoring and mitigating general financial system vulnerabilities, which can be affected by climate change over the long-term just like any number of other sources of risk? Before I answer, let me offer some definitions to make sure we're all talking about the same things.

Climate-related financial risks are generally separated into two groups: physical risks and transition risks. Physical risks include the potential higher frequency and severity of acute events, such as fires, heatwaves, and hurricanes, as well as slower moving events like rising sea levels. Transition risks refer to those risks associated with an economy and society in transition to one that produces less greenhouse gases. These can owe to government policy changes, changes in consumer preferences, and technology transitions. The question is not whether these risks could result in losses for individuals or companies. The question is whether these risks are unique enough to merit special treatment in our financial stability framework.

Let's start with physical risks. Unfortunately, like every year, it is possible we will experience forest fires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters in the coming months. These events, of course, are devastating to local communities. But they are not material enough to pose an outsized risk to the overall U.S. economy.

Broadly speaking, physical risks could affect the financial system through two related channels. First, physical risks can have a direct impact on property values. Hurricanes, fires, and rising sea levels can all drive down the values of properties. That in turn could put stress on financial institutions that lend against those properties, which could lead them to curb their lending, and suppress economic growth. The losses that individual property owners can realize might be devastating, but evidence I've seen so far suggests that these sorts of events don't have much of an effect on bank performance. That may be in part attributable to banks and other investors effectively pricing physical risks from climate change into loan contracts. For example, recently researchers have found that heat stress—a climate physical risk that is likely to affect the economy—has been priced into bond spreads and stock returns since around 2013. In addition, while it is difficult to isolate the effects of weather events on the broader economy, there is evidence to suggest severe weather events like hurricanes do not likely have an outsized effect on growth rates in countries like the United States.

Over time, it is possible some of these physical risks could contribute to an exodus of people from certain cities or regions. For example, some worry that rising sea levels could significantly change coastal regions. While the cause may be different, the experience of broad property value declines is not a new one. We have had entire American cities that have experienced significant declines in population and property values over time. Take, for example, Detroit. In 1950, Detroit was the fifth largest city in the United States, but now it isn't even in the top 20, after losing two-thirds of its population. I'm thrilled to see that Detroit has made a comeback in recent years, but the relocation of the automobile industry took a serious toll on the city and its people. Yet the decline in Detroit's population, and commensurate decline in property values, did not pose a financial stability risk to the United States. What makes the potential future risk of a population decline in coastal cities different?

Second, and a more compelling concern, is the notion that property value declines could occur more-or-less instantaneously and on a large scale when, say, property insurers leave a region en masse. That sort of rapid decline in property values, which serve as collateral on loans, could certainly result in losses for banks and other financial intermediaries. But there is a growing body of literature that suggests economic agents are already adjusting behavior to account for risks associated with climate change. That should mitigate the risk of these potential "Minsky moments." For the sake of argument though, suppose a great repricing does occur; would those losses be big enough to spill over into the broader financial system? Just as a point of comparison, let's turn back to the stress tests I mentioned earlier. Each year the Federal Reserve stresses the largest banks against a hypothetical severe macroeconomic scenario. The stress tests don't cover all risks, of course, but that scenario typically assumes broad real estate price declines of more than 25 percent across the United States. In last year's stress test, the largest banks were able to absorb nearly $100 billion in losses on loans collateralized by real estate, in addition to another half a trillion dollars of losses on other positions.

What about transition risks? Transition risks are generally neither near-term nor likely to be material given their slow-moving nature and the ability of economic agents to price transition costs into contracts. There seems to be a consensus that orderly transitions will not pose a risk to financial stability. In that case, changes would be gradual and predictable. Households and businesses are generally well prepared to adjust to slow-moving and predicable changes. As are banks. For example, if banks know that certain industries will gradually become less profitable or assets pledged as collateral will become stranded, they will account for that in their loan pricing, loan duration, and risk assessments. And, because assets held by banks in the United States reprice in less than five years on average, there is ample time to adjust to all but the most abrupt of transitions.

But what if the transition is disorderly? One argument is that uncertainty associated with a disorderly transition will make it difficult for households and businesses to plan. It is certainly plausible that there could be swings in policy, and those swings could lead to changes in earnings expectations for companies, property values, and the value of commodities. But policy development is often disorderly and subject to the uncertainty of changing economic realities. In the United States, we have a long history of sweeping policy changes ranging from revisions to the tax code to things like changes in healthcare coverage and environmental policies. While these policy changes can certainly affect the composition of industries, the connection to broader financial stability is far less clear. And when policies are found to have large and damaging consequences, policymakers always have, and frequently make use of, the option to adjust course to limit those disruptions.

There are also concerns that technology development associated with climate change will be disorderly. Much technology development is disorderly. That is why innovators are often referred to as "disruptors." So, what makes climate-related innovations more disruptive or less predictable than other innovations? Like the innovations of the automobile and the cell phone, I'd expect those stemming from the development of cleaner fuels and more efficient machines to be welfare-increasing on net.

So where does that leave us? I don't see a need for special treatment for climate-related risks in our financial stability monitoring and policies. As policymakers, we must balance the broad set of risks we face, and we have a responsibility to prioritize using evidence and analysis. Based on what I've seen so far, I believe that placing an outsized focus on climate-related risks is not needed, and the Federal Reserve should focus on more near-term and material risks in keeping with our mandate.

* * *

And cue the outrage mob...

Government

The Great Replacement Loophole: Illegal Immigrants Score 5-Year Work Benefit While “Waiting” For Deporation, Asylum

The Great Replacement Loophole: Illegal Immigrants Score 5-Year Work Benefit While "Waiting" For Deporation, Asylum

Over the past several…

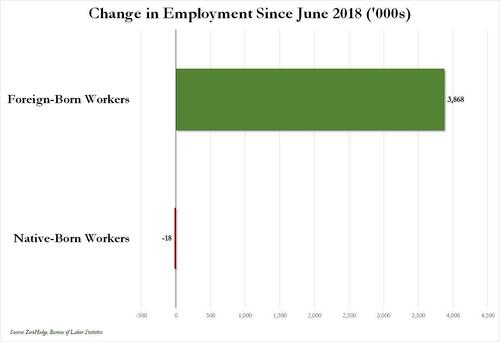

Over the past several months we've pointed out that there has been zero job creation for native-born workers since the summer of 2018...

... and that since Joe Biden was sworn into office, most of the post-pandemic job gains the administration continuously brags about have gone foreign-born (read immigrants, mostly illegal ones) workers.

And while the left might find this data almost as verboten as FBI crime statistics - as it directly supports the so-called "great replacement theory" we're not supposed to discuss - it also coincides with record numbers of illegal crossings into the United States under Biden.

In short, the Biden administration opened the floodgates, 10 million illegal immigrants poured into the country, and most of the post-pandemic "jobs recovery" went to foreign-born workers, of which illegal immigrants represent the largest chunk.

'But Tyler, illegal immigrants can't possibly work in the United States whilst awaiting their asylum hearings,' one might hear from the peanut gallery. On the contrary: ever since Biden reversed a key aspect of Trump's labor policies, all illegal immigrants - even those awaiting deportation proceedings - have been given carte blanche to work while awaiting said proceedings for up to five years...

... something which even Elon Musk was shocked to learn.

Wow, learn something new every day https://t.co/8MDtEEZGam

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 10, 2024

Which leads us to another question: recall that the primary concern for the Biden admin for much of 2022 and 2023 was soaring prices, i.e., relentless inflation in general, and rising wages in particular, which in turn prompted even Goldman to admit two years ago that the diabolical wage-price spiral had been unleashed in the US (diabolical, because nothing absent a major economic shock, read recession or depression, can short-circuit it once it is in place).

Well, there is one other thing that can break the wage-price spiral loop: a flood of ultra-cheap illegal immigrant workers. But don't take our word for it: here is Fed Chair Jerome Powell himself during his February 60 Minutes interview:

PELLEY: Why was immigration important?

POWELL: Because, you know, immigrants come in, and they tend to work at a rate that is at or above that for non-immigrants. Immigrants who come to the country tend to be in the workforce at a slightly higher level than native Americans do. But that's largely because of the age difference. They tend to skew younger.

PELLEY: Why is immigration so important to the economy?

POWELL: Well, first of all, immigration policy is not the Fed's job. The immigration policy of the United States is really important and really much under discussion right now, and that's none of our business. We don't set immigration policy. We don't comment on it.

I will say, over time, though, the U.S. economy has benefited from immigration. And, frankly, just in the last, year a big part of the story of the labor market coming back into better balance is immigration returning to levels that were more typical of the pre-pandemic era.

PELLEY: The country needed the workers.

POWELL: It did. And so, that's what's been happening.

Translation: Immigrants work hard, and Americans are lazy. But much more importantly, since illegal immigrants will work for any pay, and since Biden's Department of Homeland Security, via its Citizenship and Immigration Services Agency, has made it so illegal immigrants can work in the US perfectly legally for up to 5 years (if not more), one can argue that the flood of illegals through the southern border has been the primary reason why inflation - or rather mostly wage inflation, that all too critical component of the wage-price spiral - has moderated in in the past year, when the US labor market suddenly found itself flooded with millions of perfectly eligible workers, who just also happen to be illegal immigrants and thus have zero wage bargaining options.

None of this is to suggest that the relentless flood of immigrants into the US is not also driven by voting and census concerns - something Elon Musk has been pounding the table on in recent weeks, and has gone so far to call it "the biggest corruption of American democracy in the 21st century", but in retrospect, one can also argue that the only modest success the Biden admin has had in the past year - namely bringing inflation down from a torrid 9% annual rate to "only" 3% - has also been due to the millions of illegals he's imported into the country.

We would be remiss if we didn't also note that this so often carries catastrophic short-term consequences for the social fabric of the country (the Laken Riley fiasco being only the latest example), not to mention the far more dire long-term consequences for the future of the US - chief among them the trillions of dollars in debt the US will need to incur to pay for all those new illegal immigrants Democrat voters and low-paid workers. This is on top of the labor revolution that will kick in once AI leads to mass layoffs among high-paying, white-collar jobs, after which all those newly laid off native-born workers hoping to trade down to lower paying (if available) jobs will discover that hardened criminals from Honduras or Guatemala have already taken them, all thanks to Joe Biden.

Spread & Containment

‘I couldn’t stand the pain’: the Turkish holiday resort that’s become an emergency dental centre for Britons who can’t get treated at home

The crisis in NHS dentistry is driving increasing numbers abroad for treatment. Here are some of their stories.

It’s a hot summer day in the Turkish city of Antalya, a Mediterranean resort with golden beaches, deep blue sea and vibrant nightlife. The pool area of the all-inclusive resort is crammed with British people on sun loungers – but they aren’t here for a holiday. This hotel is linked to a dental clinic that organises treatment packages, and most of these guests are here to see a dentist.

From Norwich, two women talk about gums and injections. A man from Wales holds a tissue close to his mouth and spits blood – he has just had two molars extracted.

The dental clinic organises everything for these dental “tourists” throughout their treatment, which typically lasts from three to 15 days. The stories I hear of what has caused them to travel to Turkey are strikingly similar: all have struggled to secure dental treatment at home on the NHS.

“The hotel is nice and some days I go to the beach,” says Susan*, a hairdresser in her mid-30s from Norwich. “But really, we aren’t tourists like in a proper holiday. We come here because we have no choice. I couldn’t stand the pain.”

This is Susan’s second visit to Antalya. She explains that her ordeal started two years earlier:

I went to an NHS dentist who told me I had gum disease … She did some cleaning to my teeth and gums but it got worse. When I ate, my teeth were moving … the gums were bleeding and it was very painful. I called to say I was in pain but the clinic was not accepting NHS patients any more.

The only option the dentist offered Susan was to register as a private patient:

I asked how much. They said £50 for x-rays and then if the gum disease got worse, £300 or so for extraction. Four of them were moving – imagine: £1,200 for losing your teeth! Without teeth I’d lose my clients, but I didn’t have the money. I’m a single mum. I called my mum and cried.

Susan’s mother told her about a friend of hers who had been to Turkey for treatment, then together they found a suitable clinic:

The prices are so much cheaper! Tooth extraction, x-rays, consultations – it all comes included. The flight and hotel for seven days cost the same as losing four teeth in Norwich … I had my lower teeth removed here six months ago, now I’ve got implants … £2,800 for everything – hotel, transfer, treatments. I only paid the flights separately.

In the UK, roughly half the adult population suffers from periodontitis – inflammation of the gums caused by plaque bacteria that can lead to irreversible loss of gums, teeth, and bone. Regular reviews by a dentist or hygienist are required to manage this condition. But nine out of ten dental practices cannot offer NHS appointments to new adult patients, while eight in ten are not accepting new child patients.

Some UK dentists argue that Britons who travel abroad for treatment do so mainly for cosmetic procedures. They warn that dental tourism is dangerous, and that if their treatment goes wrong, dentists in the UK will be unable to help because they don’t want to be responsible for further damage. Susan shrugs this off:

Dentists in England say: ‘If you go to Turkey, we won’t touch you [afterwards].’ But I don’t worry because there are no appointments at home anyway. They couldn’t help in the first place, and this is why we are in Turkey.

‘How can we pay all this money?’

As a social anthropologist, I travelled to Turkey a number of times in 2023 to investigate the crisis of NHS dentistry, and the journeys abroad that UK patients are increasingly making as a result. I have relatives in Istanbul and have been researching migration and trading patterns in Turkey’s largest city since 2016.

In August 2023, I visited the resort in Antalya, nearly 400 miles south of Istanbul. As well as Susan, I met a group from a village in Wales who said there was no provision of NHS dentistry back home. They had organised a two-week trip to Turkey: the 12-strong group included a middle-aged couple with two sons in their early 20s, and two couples who were pensioners. By going together, Anya tells me, they could support each other through their different treatments:

I’ve had many cavities since I was little … Before, you could see a dentist regularly – you didn’t even think about it. If you had pain or wanted a regular visit, you phoned and you went … That was in the 1990s, when I went to the dentist maybe every year.

Anya says that once she had children, her family and work commitments meant she had no time to go to the dentist. Then, years later, she started having serious toothache:

Every time I chewed something, it hurt. I ate soups and soft food, and I also lost weight … Even drinking was painful – tea: pain, cold water: pain. I was taking paracetamol all the time! I went to the dentist to fix all this, but there were no appointments.

Anya was told she would have to wait months, or find a dentist elsewhere:

A private clinic gave me a list of things I needed done. Oh my God, almost £6,000. My husband went too – same story. How can we pay all this money? So we decided to come to Turkey. Some people we know had been here, and others in the village wanted to come too. We’ve brought our sons too – they also need to be checked and fixed. Our whole family could be fixed for less than £6,000.

By the time they travelled, Anya’s dental problems had turned into a dental emergency. She says she could not live with the pain anymore, and was relying on paracetamol.

In 2023, about 6 million adults in the UK experienced protracted pain (lasting more than two weeks) caused by toothache. Unintentional paracetamol overdose due to dental pain is a significant cause of admissions to acute medical units. If left untreated, tooth infections can spread to other parts of the body and cause life-threatening complications – and on rare occasions, death.

In February 2024, police were called to manage hundreds of people queuing outside a newly opened dental clinic in Bristol, all hoping to be registered or seen by an NHS dentist. One in ten Britons have admitted to performing “DIY dentistry”, of which 20% did so because they could not find a timely appointment. This includes people pulling out their teeth with pliers and using superglue to repair their teeth.

In the 1990s, dentistry was almost entirely provided through NHS services, with only around 500 solely private dentists registered. Today, NHS dentist numbers in England are at their lowest level in a decade, with 23,577 dentists registered to perform NHS work in 2022-23, down 695 on the previous year. Furthermore, the precise division of NHS and private work that each dentist provides is not measured.

The COVID pandemic created longer waiting lists for NHS treatment in an already stretched public service. In Bridlington, Yorkshire, people are now reportedly having to wait eight-to-nine years to get an NHS dental appointment with the only remaining NHS dentist in the town.

In his book Patients of the State (2012), Argentine sociologist Javier Auyero describes the “indignities of waiting”. It is the poor who are mostly forced to wait, he writes. Queues for state benefits and public services constitute a tangible form of power over the marginalised. There is an ethnic dimension to this story, too. Data suggests that in the UK, patients less likely to be effective in booking an NHS dental appointment are non-white ethnic groups and Gypsy or Irish travellers, and that it is particularly challenging for refugees and asylum-seekers to access dental care.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

In 2022, I experienced my own dental emergency. An infected tooth was causing me debilitating pain, and needed root canal treatment. I was advised this would cost £71 on the NHS, plus £307 for a follow-up crown – but that I would have to wait months for an appointment. The pain became excruciating – I could not sleep, let alone wait for months. In the same clinic, privately, I was quoted £1,300 for the treatment (more than half my monthly income at the time), or £295 for a tooth extraction.

I did not want to lose my tooth because of lack of money. So I bought a flight to Istanbul immediately for the price of the extraction in the UK, and my tooth was treated with root canal therapy by a private dentist there for £80. Including the costs of travelling, the total was a third of what I was quoted to be treated privately in the UK. Two years on, my treated tooth hasn’t given me any more problems.

A better quality of life

Not everyone is in Antalya for emergency procedures. The pensioners from Wales had contacted numerous clinics they found on the internet, comparing prices, treatments and hotel packages at least a year in advance, in a carefully planned trip to get dental implants – artificial replacements for tooth roots that help support dentures, crowns and bridges.

In Turkey, all the dentists I speak to (most of whom cater mainly for foreigners, including UK nationals) consider implants not a cosmetic or luxurious treatment, but a development in dentistry that gives patients who are able to have the procedure a much better quality of life. This procedure is not available on the NHS for most of the UK population, and the patients I meet in Turkey could not afford implants in private clinics back home.

Paul is in Antalya to replace his dentures, which have become uncomfortable and irritating to his gums, with implants. He says he couldn’t find an appointment to see an NHS dentist. His wife Sonia went through a similar procedure the year before and is very satisfied with the results, telling me: “Why have dentures that you need to put in a glass overnight, in the old style? If you can have implants, I say, you’re better off having them.”

Most of the dental tourists I meet in Antalya are white British: this city, known as the Turkish Riviera, has developed an entire economy catering to English-speaking tourists. In 2023, more than 1.3 million people visited the city from the UK, up almost 15% on the previous year.

Read more: NHS dentistry is in crisis – are overseas dentists the answer?

In contrast, the Britons I meet in Istanbul are predominantly from a non-white ethnic background. Omar, a pensioner of Pakistani origin in his early 70s, has come here after waiting “half a year” for an NHS appointment to fix the dental bridge that is causing him pain. Omar’s son had been previously for a hair transplant, and was offered a free dental checkup by the same clinic, so he suggested it to his father. Having worked as a driver for a manufacturing company for two decades in Birmingham, Omar says he feels disappointed to have contributed to the British economy for so long, only to be “let down” by the NHS:

At home, I must wait and wait and wait to get a bridge – and then I had many problems with it. I couldn’t eat because the bridge was uncomfortable and I was in pain, but there were no appointments on the NHS. I asked a private dentist and they recommended implants, but they are far too expensive [in the UK]. I started losing weight, which is not a bad thing at the beginning, but then I was worrying because I couldn’t chew and eat well and was losing more weight … Here in Istanbul, I got dental implants – US$500 each, problem solved! In England, each implant is maybe £2,000 or £3,000.

In the waiting area of another clinic in Istanbul, I meet Mariam, a British woman of Iraqi background in her late 40s, who is making her second visit to the dentist here. Initially, she needed root canal therapy after experiencing severe pain for weeks. Having been quoted £1,200 in a private clinic in outer London, Mariam decided to fly to Istanbul instead, where she was quoted £150 by a dentist she knew through her large family. Even considering the cost of the flight, Mariam says the decision was obvious:

Dentists in England are so expensive and NHS appointments so difficult to find. It’s awful there, isn’t it? Dentists there blamed me for my rotten teeth. They say it’s my fault: I don’t clean or I ate sugar, or this or that. I grew up in a village in Iraq and didn’t go to the dentist – we were very poor. Then we left because of war, so we didn’t go to a dentist … When I arrived in London more than 20 years ago, I didn’t speak English, so I still didn’t go to the dentist … I think when you move from one place to another, you don’t go to the dentist unless you are in real, real pain.

In Istanbul, Mariam has opted not only for the urgent root canal treatment but also a longer and more complex treatment suggested by her consultant, who she says is a renowned doctor from Syria. This will include several extractions and implants of back and front teeth, and when I ask what she thinks of achieving a “Hollywood smile”, Mariam says:

Who doesn’t want a nice smile? I didn’t come here to be a model. I came because I was in pain, but I know this doctor is the best for implants, and my front teeth were rotten anyway.

Dentists in the UK warn about the risks of “overtreatment” abroad, but Mariam appears confident that this is her opportunity to solve all her oral health problems. Two of her sisters have already been through a similar treatment, so they all trust this doctor.

The UK’s ‘dental deserts’

To get a fuller understanding of the NHS dental crisis, I’ve also conducted 20 interviews in the UK with people who have travelled or were considering travelling abroad for dental treatment.

Joan, a 50-year-old woman from Exeter, tells me she considered going to Turkey and could have afforded it, but that her back and knee problems meant she could not brave the trip. She has lost all her lower front teeth due to gum disease and, when I meet her, has been waiting 13 months for an NHS dental appointment. Joan tells me she is living in “shame”, unable to smile.

In the UK, areas with extremely limited provision of NHS dental services – known as as “dental deserts” – include densely populated urban areas such as Portsmouth and Greater Manchester, as well as many rural and coastal areas.

In Felixstowe, the last dentist taking NHS patients went private in 2023, despite the efforts of the activist group Toothless in Suffolk to secure better access to NHS dentists in the area. It’s a similar story in Ripon, Yorkshire, and in Dumfries & Galloway, Scotland, where nearly 25,000 patients have been de-registered from NHS dentists since 2021.

Data shows that 2 million adults must travel at least 40 miles within the UK to access dental care. Branding travel for dental care as “tourism” carries the risk of disguising the elements of duress under which patients move to restore their oral health – nationally and internationally. It also hides the immobility of those who cannot undertake such journeys.

The 90-year-old woman in Dumfries & Galloway who now faces travelling for hours by bus to see an NHS dentist can hardly be considered “tourism” – nor the Ukrainian war refugees who travelled back from West Sussex and Norwich to Ukraine, rather than face the long wait to see an NHS dentist.

Many people I have spoken to cannot afford the cost of transport to attend dental appointments two hours away – or they have care responsibilities that make it impossible. Instead, they are forced to wait in pain, in the hope of one day securing an appointment closer to home.

‘Your crisis is our business’

The indignities of waiting in the UK are having a big impact on the lives of some local and foreign dentists in Turkey. Some neighbourhoods are rapidly changing as dental and other health clinics, usually in luxurious multi-storey glass buildings, mushroom. In the office of one large Istanbul medical complex with sections for hair transplants and dentistry (plus one linked to a hospital for more extensive cosmetic surgery), its Turkish owner and main investor tells me:

Your crisis is our business, but this is a bazaar. There are good clinics and bad clinics, and unfortunately sometimes foreign patients do not know which one to choose. But for us, the business is very good.

This clinic only caters to foreign patients. The owner, an architect by profession who also developed medical clinics in Brazil, describes how COVID had a major impact on his business:

When in Europe you had COVID lockdowns, Turkey allowed foreigners to come. Many people came for ‘medical tourism’ – we had many patients for cosmetic surgery and hair transplants. And that was when the dental business started, because our patients couldn’t see a dentist in Germany or England. Then more and more patients started to come for dental treatments, especially from the UK and Ireland. For them, it’s very, very cheap here.

The reasons include the value of the Turkish lira relative to the British pound, the low cost of labour, the increasing competition among Turkish clinics, and the sheer motivation of dentists here. While most dentists catering to foreign patients are from Turkey, others have arrived seeking refuge from war and violence in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran and beyond. They work diligently to rebuild their lives, careers and lost wealth.

Regardless of their origin, all dentists in Turkey must be registered and certified. Hamed, a Syrian dentist and co-owner of a new clinic in Istanbul catering to European and North American patients, tells me:

I know that you say ‘Syrian’ and people think ‘migrant’, ‘refugee’, and maybe think ‘how can this dentist be good?’ – but Syria, before the war, had very good doctors and dentists. Many of us came to Turkey and now I have a Turkish passport. I had to pass the exams to practise dentistry here – I study hard. The exams are in Turkish and they are difficult, so you cannot say that Syrian doctors are stupid.

Hamed talks excitedly about the latest technology that is coming to his profession: “There are always new materials and techniques, and we cannot stop learning.” He is about to travel to Paris to an international conference:

I can say my techniques are very advanced … I bet I put more implants and do more bone grafting and surgeries every week than any dentist you know in England. A good dentist is about practice and hand skills and experience. I work hard, very hard, because more and more patients are arriving to my clinic, because in England they don’t find dentists.

While there is no official data about the number of people travelling from the UK to Turkey for dental treatment, investors and dentists I speak to consider that numbers are rocketing. From all over the world, Turkey received 1.2 million visitors for “medical tourism” in 2022, an increase of 308% on the previous year. Of these, about 250,000 patients went for dentistry. One of the most renowned dental clinics in Istanbul had only 15 British patients in 2019, but that number increased to 2,200 in 2023 and is expected to reach 5,500 in 2024.

Like all forms of medical care, dental treatments carry risks. Most clinics in Turkey offer a ten-year guarantee for treatments and a printed clinical history of procedures carried out, so patients can show this to their local dentists and continue their regular annual care in the UK. Dental treatments, checkups and maintaining a good oral health is a life-time process, not a one-off event.

Many UK patients, however, are caught between a rock and a hard place – criticised for going abroad, yet unable to get affordable dental care in the UK before and after their return. The British Dental Association has called for more action to inform these patients about the risks of getting treated overseas – and has warned UK dentists about the legal implications of treating these patients on their return. But this does not address the difficulties faced by British patients who are being forced to go abroad in search of affordable, often urgent dental care.

A global emergency

The World Health Organization states that the explosion of oral disease around the world is a result of the “negligent attitude” that governments, policymakers and insurance companies have towards including oral healthcare under the umbrella of universal healthcare. It as if the health of our teeth and mouth is optional; somehow less important than treatment to the rest of our body. Yet complications from untreated tooth decay can lead to hospitalisation.

The main causes of oral health diseases are untreated tooth decay, severe gum disease, toothlessness, and cancers of the lip and oral cavity. Cases grew during the pandemic, when little or no attention was paid to oral health. Meanwhile, the global cosmetic dentistry market is predicted to continue growing at an annual rate of 13% for the rest of this decade, confirming the strong relationship between socioeconomic status and access to oral healthcare.

In the UK since 2018, there have been more than 218,000 admissions to hospital for rotting teeth, of which more than 100,000 were children. Some 40% of children in the UK have not seen a dentist in the past 12 months. The role of dentists in prevention of tooth decay and its complications, and in the early detection of mouth cancer, is vital. While there is a 90% survival rate for mouth cancer if spotted early, the lack of access to dental appointments is causing cases to go undetected.

The reasons for the crisis in NHS dentistry are complex, but include: the real-term cuts in funding to NHS dentistry; the challenges of recruitment and retention of dentists in rural and coastal areas; pay inequalities facing dental nurses, most of them women, who are being badly hit by the cost of living crisis; and, in England, the 2006 Dental Contract that does not remunerate dentists in a way that encourages them to continue seeing NHS patients.

The UK is suffering a mass exodus of the public dentistry workforce, with workers leaving the profession entirely or shifting to the private sector, where payments and life-work balance are better, bureaucracy is reduced, and prospects for career development look much better. A survey of general dental practitioners found that around half have reduced their NHS work since the pandemic – with 43% saying they were likely to go fully private, and 42% considering a career change or taking early retirement.

Reversing the UK’s dental crisis requires more commitment to substantial reform and funding than the “recovery plan” announced by Victoria Atkins, the secretary of state for health and social care, on February 7.

The stories I have gathered show that people travelling abroad for dental treatment don’t see themselves as “tourists” or vanity-driven consumers of the “Hollywood smile”. Rather, they have been forced by the crisis in NHS dentistry to seek out a service 1,500 miles away in Turkey that should be a basic, affordable right for all, on their own doorstep.

*Names in this article have been changed to protect the anonymity of the interviewees.

For you: more from our Insights series:

GP crisis: how did things go so wrong, and what needs to change?

Insomnia: how chronic sleep problems can lead to a spiralling decline in mental health

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Diana Ibanez Tirado receives funding from the School of Global Studies, University of Sussex.

pound pandemic treatment therapy spread recovery iran brazil european europe uk germany ukraine world health organizationInternational

Beloved mall retailer files Chapter 7 bankruptcy, will liquidate

The struggling chain has given up the fight and will close hundreds of stores around the world.

It has been a brutal period for several popular retailers. The fallout from the covid pandemic and a challenging economic environment have pushed numerous chains into bankruptcy with Tuesday Morning, Christmas Tree Shops, and Bed Bath & Beyond all moving from Chapter 11 to Chapter 7 bankruptcy liquidation.

In all three of those cases, the companies faced clear financial pressures that led to inventory problems and vendors demanding faster, or even upfront payment. That creates a sort of inevitability.

Related: Beloved retailer finds life after bankruptcy, new famous owner

When a retailer faces financial pressure it sets off a cycle where vendors become wary of selling them items. That leads to barren shelves and no ability for the chain to sell its way out of its financial problems.

Once that happens bankruptcy generally becomes the only option. Sometimes that means a Chapter 11 filing which gives the company a chance to negotiate with its creditors. In some cases, deals can be worked out where vendors extend longer terms or even forgive some debts, and banks offer an extension of loan terms.

In other cases, new funding can be secured which assuages vendor concerns or the company might be taken over by its vendors. Sometimes, as was the case with David's Bridal, a new owner steps in, adds new money, and makes deals with creditors in order to give the company a new lease on life.

It's rare that a retailer moves directly into Chapter 7 bankruptcy and decides to liquidate without trying to find a new source of funding.

Image source: Getty Images

The Body Shop has bad news for customers

The Body Shop has been in a very public fight for survival. Fears began when the company closed half of its locations in the United Kingdom. That was followed by a bankruptcy-style filing in Canada and an abrupt closure of its U.S. stores on March 4.

"The Canadian subsidiary of the global beauty and cosmetics brand announced it has started restructuring proceedings by filing a Notice of Intention (NOI) to Make a Proposal pursuant to the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (Canada). In the same release, the company said that, as of March 1, 2024, The Body Shop US Limited has ceased operations," Chain Store Age reported.

A message on the company's U.S. website shared a simple message that does not appear to be the entire story.

"We're currently undergoing planned maintenance, but don't worry we're due to be back online soon."

That same message is still on the company's website, but a new filing makes it clear that the site is not down for maintenance, it's down for good.

The Body Shop files for Chapter 7 bankruptcy

While the future appeared bleak for The Body Shop, fans of the brand held out hope that a savior would step in. That's not going to be the case.

The Body Shop filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in the United States.

"The US arm of the ethical cosmetics group has ceased trading at its 50 outlets. On Saturday (March 9), it filed for Chapter 7 insolvency, under which assets are sold off to clear debts, putting about 400 jobs at risk including those in a distribution center that still holds millions of dollars worth of stock," The Guardian reported.

After its closure in the United States, the survival of the brand remains very much in doubt. About half of the chain's stores in the United Kingdom remain open along with its Australian stores.

The future of those stores remains very much in doubt and the chain has shared that it needs new funding in order for them to continue operating.

The Body Shop did not respond to a request for comment from TheStreet.

bankruptcy pandemic canada-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex