Uncategorized

Comparing this housing market recession to 2008

The housing market recession we’ve seen this year is significantly different than 2008. Here’s what you should pay attention to.

As we close out 2022, it’s time to reflect on a historic year for the housing market, which was even crazier than the COVID-19 year of 2020. There are similarities and significant differences between the housing recession we’ve seen this year versus 2008, and looking at specific factors in both timeframes gives us an idea of what to expect in 2023.

First, we must define what we mean by recession. Our general economy is not yet in a recession, but housing has been in one since the summer. For me, it’s straightforward: it’s when we see these four things happen in any sector of our economy:

1. Sales fall. Housing demand has fallen noticeably this year.

2. Production falls. Housing permits and starts are falling now, even with the backlog of homes in the system.

3. Jobs are being lost. The housing sector — especially real estate and mortgage — has seen significant layoffs, while the general economy will create more than 4 million jobs in 2022.

4. Incomes go down. With less transaction volume, general incomes in the housing sector are falling.

A few months ago, I was asked to go on CNBC and talk about why I call this a housing recession and why this year reminds me a lot of 2018, but much worse on the four items above.

It is crazy to think we are seeing these four things happen in the housing market considering that even in March of this year we were seeing bidding wars accelerate before mortgage rates rose. That is how fast things changed — a by-product of a sector where the prices of homes were getting out of control after 2020.

Then we had the biggest mortgage rate shock in recent history and yet even with that, we will have over 5 million total home sales this year. Sometimes this discussion gets off the rails because people tell me home prices are up in 2022 so housing can’t be in a recession.

That is precisely the wrong way to look at housing economics: higher home prices have nothing to do with housing being in a recession, as I showed above. Housing went into recession in 2006 and prices weren’t collapsing that year either.

Let’s look at the recessionary factors we see now versus 2008.

Home sales

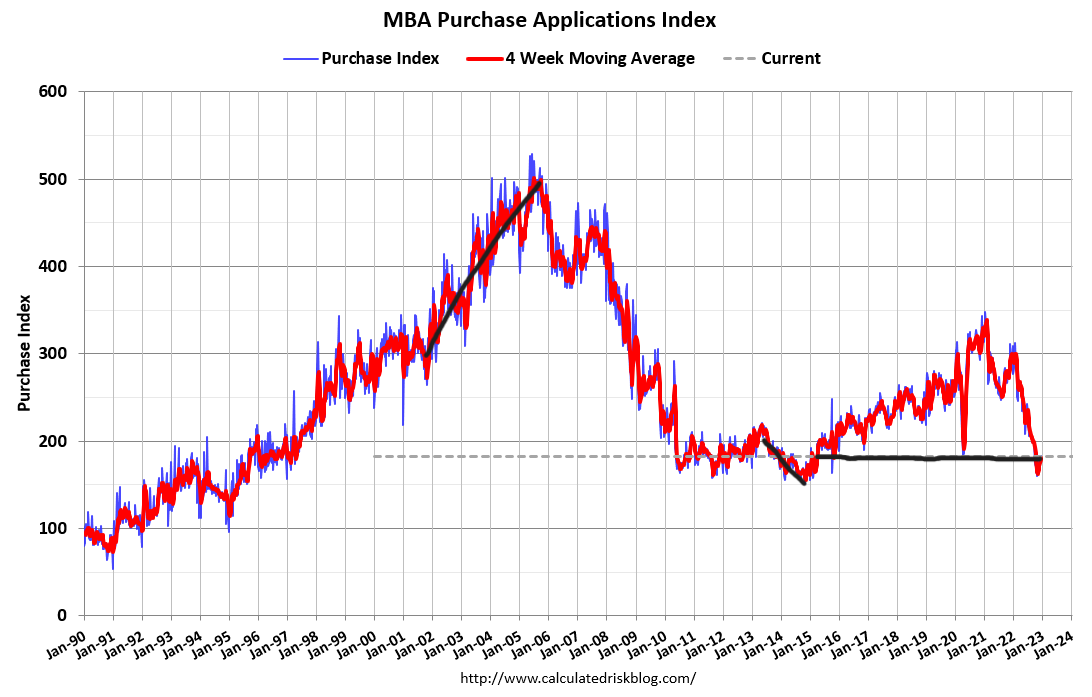

The housing market of 2002-2005 had four years of sales growth facilitated by credit. As we can see below, the purchase application data had four years of growth, peaking in 2005 and then collapsing. In our current market, purchase application data recently fell below the 2008 level.

However, what isn’t identical is that we have not had a massive sales boom like we saw from 2002-2005. We only had one year of growth in the purchase application data from 2020-2021. The COVID-19 pause and rebound meant that the end of the year in 2020 was artificially high, so I can make the case that we had decent two years of growth, but that’s all. This is significantly different than the period from 2002-2005 when credit expansion was booming.

Existing home sales has seen a waterfall dive in demand, but this has happened in less than a year. During the housing bubble years, home sales peaked in 2005 and it took two years to get back to the sales levels we are trending at today. As we can see below, we had times in the previous expansion when rates rose and sales trends headed to under 5 million. Now, with one more report left in the year, we might break under 4 million.

Outside of COVID-19, we have yet to see pending home sales hit levels that low level this century. Part of the issue is that mortgage rates moved up so fast that many sellers quit this year as well.

Key thing to remember: A traditional seller is also usually a buyer . This common-sense reality has been lost in the discussion of housing market economics for a long time because people kept pushing the false narrative of supply spikes — which means people would sell their homes to be homeless. In fact, when traditional primary resident homeowners list their homes, they typically buy another home.

When mortgage rates spiked up as much as they did this year, it wasn’t financially appealing to some sellers to purchase their homes at rates of 6.25%-7.37%. This has led to many people not listing their homes to sell and facilitated a more considerable decline in home sales than we would traditionally see. This now goes into a subject matter that is a striking difference between 2022 versus 2008: Inventory and Credit.

Housing inventory

This aspect of the housing market is where we see the biggest divergence between 2008 and today. Total housing inventory today — using the NAR data — stands at 1.14 million. We have a good probability over the next two existing home sales reports to break under 1 million total active listings, which would mean that we will start 2023 with the secon-lowest level listings ever in history.

As I have explained, this started in the year 2000, when total active listings grew from 2 million to 2.5 million in 2005. Except we had many years of a credit sales boom on debt structures that weren’t sustainable. So, when housing peaked in 2005, we had a flood of inventory from home sellers who couldn’t buy a home, and that flood allowed the list to spike to over 4 million in 2007.

As you can see below, today — a few days away from 2023 —with existing home sales trending at 2007 sales levels, it is strikingly different.

The housing economy is built on housing construction, and the recession that started in June meant housing permits were going to fall, which they have. The issue is that when housingw as in a recession in 2007, we had a massive spike in supply. That isn’t the case now and housing permits have legs to keep going lower as long as mortgage rates stay high.

One saving grace is right now is that the builders still have a massive backlog of homes to build, especially two-unit rental units that amount to nearly 1 million added supply coming online next year. This is a big plus in fighting inflation.

Key thing to remember: The best way to fight inflation is more supply. If you’re trying to fight inflation by destroying demand, it’s not the most effective measure and can ruin future production. Depending on how the next two years go, this will be a topic of conversation if housing permits fall over the next two years.

The good news for 2023 is that we still have supply coming, and we all should be rooting for housing completion data to improve next year. As you can see from the chart below of housing completion data, sales are falling, but completions have gone nowhere for some time now. This is because we didn’t have the credit sales boom from 2020-2022 that we saw from 2002-2005.

Housing credit

The most significant difference between the recession today and 2008 is housing credit. In 2008, the rise of foreclosures and bankruptcy were waving red flags before the job-loss recession even happened. Today, it’s the complete opposite story: the 2005 bankruptcy reform laws and the 2010 Qualified Mortgage laws laid the foundation for the best housing credit profiles recorded in U.S. history.

From 2005 to 2008, we saw a rise in foreclosures, all before the job-loss recession happened. That isn’t what residential housing credit risk is supposed to look like.

We now have real credit risk, as prices are falling from the peak in some areas; late-cycle lending risk is always traditional. People who buy homes late in an expansion and lose their jobs with no selling equity will likely lead to a foreclosure, most likely those with FHA loans. This means that the scale of defaults when the next job -oss recession happens will be small compared to 2008.

A foreclosure takes a lot of time, traditionally nine to 12 months. As we can see, once the recession started in 2008, the 90 days late + foreclosure data line took off. However, this all actually began in 2005 with the rise of new foreclosure and bankruptcy data heading toward the recession of 2008.

From Fannie Mae: The conventional single-family serious delinquency rate decreased by three basis points to 0.64% in November.

The housing reforms made housing credit boring again, and boring is sexy! Housing is the cost of the shelter to your capacity to own the debt. So, someone buys a home, their debt payment is fixed, and their wages rise every year, making their cost of shelter go down while their income grows. This has created one of the most impressive data lines for homeowners.

Mortgage debt service payments as a percent of disposable personal income have collapsed as people stayed in their homes longer and longer. With three refinancing waves since 2010, their housing debt cost versus their total wages fell. As you can see below, there is a massive difference at the end of 2022 versus 2008.

FICO score trends have been steady for 12 years. Now, we have seen people speculate that the recent rise in FICO scores for owners is credit score inflation, but the trends have stayed the same for a long time. It’s just the fact that, as a country, we originated a lot more loans during COVID-19 due to the massive wave of refinancing. People assume that was credit score inflation but in reality, the trend stayed the same.

As you can see in the chart below, the credit quality is much better now and we have no more exotic loan debt structures in the system post-2010.

On top of homeowners’ credit looking excellent, we have a lot of nested equity, and over 40% of homes in America don’t have a mortgage. So, on the credit and debt side of the equation, the housing market looks a lot different in this recession.

Housing debt adjusting to inflation isn’t even above the housing bubble peak. This is a by-product of having the weakest housing recovery in the previous expansion. I wrote about this before we got into the critical timeframe of 2020-2024, and we weren’t in a housing bubble in 2019 as so many people claimed.

So is housing in a recession? Yes, it is. Is it like 2008? Not even close.

What I’ve showed here can explain why some data look the same, and some look very different. This time around we have taken a much more aggressive hit in existing home sales in a faster amount of time. We didn’t see similar inventory spikes as we did from 2005 to 2008, nor has the housing credit market crashed.

However, we are in the early stages of housing permits getting hit, and many housing jobs were lost in 2022 due to the decline in demand for homes. The question now is, what about 2023?

Next week I will be providing my 2023 forecast, which will be written in a way I have never done before because the chaos in today’s housing market data is truly savagely unhealthy, while some of the core foundations of housing are very well intact. Happy New Year’s!

recession bankruptcy foreclosure covid-19 home sales mortgage rates real estate housing market recession recoveryUncategorized

February Employment Situation

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000…

By Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert

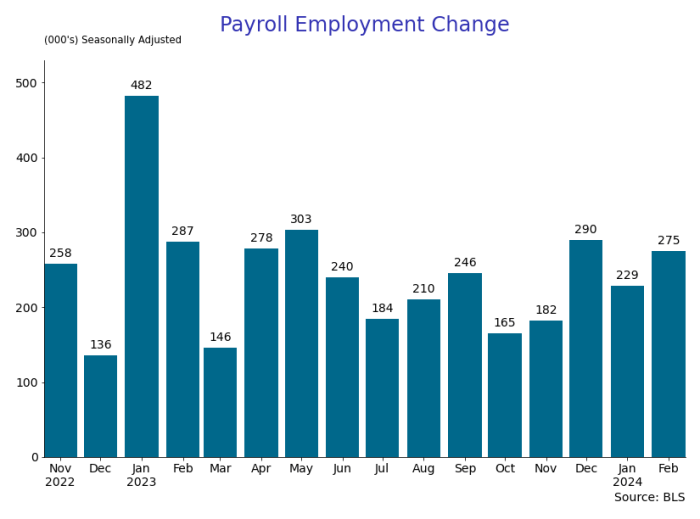

The establishment data from the BLS showed a 275,000 increase in payroll employment for February, outpacing the 230,000 average over the previous 12 months. The payroll data for January and December were revised down by a total of 167,000. The private sector added 223,000 new jobs, the largest gain since May of last year.

Temporary help services employment continues a steep decline after a sharp post-pandemic rise.

Average hours of work increased from 34.2 to 34.3. The increase, along with the 223,000 private employment increase led to a hefty increase in total hours of 5.6% at an annualized rate, also the largest increase since May of last year.

The establishment report, once again, beat “expectations;” the WSJ survey of economists was 198,000. Other than the downward revisions, mentioned above, another bit of negative news was a smallish increase in wage growth, from $34.52 to $34.57.

The household survey shows that the labor force increased 150,000, a drop in employment of 184,000 and an increase in the number of unemployed persons of 334,000. The labor force participation rate held steady at 62.5, the employment to population ratio decreased from 60.2 to 60.1 and the unemployment rate increased from 3.66 to 3.86. Remember that the unemployment rate is the number of unemployed relative to the labor force (the number employed plus the number unemployed). Consequently, the unemployment rate can go up if the number of unemployed rises holding fixed the labor force, or if the labor force shrinks holding the number unemployed unchanged. An increase in the unemployment rate is not necessarily a bad thing: it may reflect a strong labor market drawing “marginally attached” individuals from outside the labor force. Indeed, there was a 96,000 decline in those workers.

Earlier in the week, the BLS announced JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) data for January. There isn’t much to report here as the job openings changed little at 8.9 million, the number of hires and total separations were little changed at 5.7 million and 5.3 million, respectively.

As has been the case for the last couple of years, the number of job openings remains higher than the number of unemployed persons.

Also earlier in the week the BLS announced that productivity increased 3.2% in the 4th quarter with output rising 3.5% and hours of work rising 0.3%.

The bottom line is that the labor market continues its surprisingly (to some) strong performance, once again proving stronger than many had expected. This strength makes it difficult to justify any interest rate cuts soon, particularly given the recent inflation spike.

unemployment pandemic unemploymentUncategorized

Mortgage rates fall as labor market normalizes

Jobless claims show an expanding economy. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

Everyone was waiting to see if this week’s jobs report would send mortgage rates higher, which is what happened last month. Instead, the 10-year yield had a muted response after the headline number beat estimates, but we have negative job revisions from previous months. The Federal Reserve’s fear of wage growth spiraling out of control hasn’t materialized for over two years now and the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.9%. For now, we can say the labor market isn’t tight anymore, but it’s also not breaking.

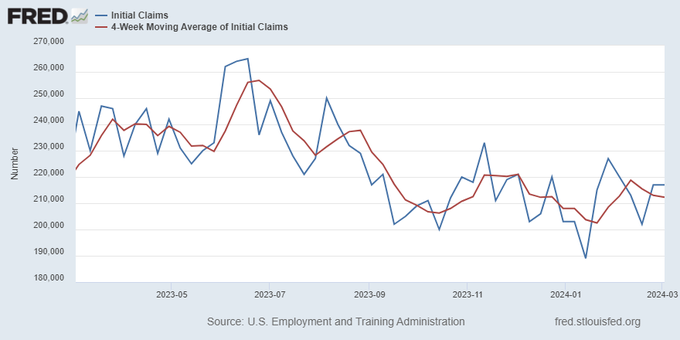

The key labor data line in this expansion is the weekly jobless claims report. Jobless claims show an expanding economy that has not lost jobs yet. We will only be in a recession once jobless claims exceed 323,000 on a four-week moving average.

From the Fed: In the week ended March 2, initial claims for unemployment insurance benefits were flat, at 217,000. The four-week moving average declined slightly by 750, to 212,250

Below is an explanation of how we got here with the labor market, which all started during COVID-19.

1. I wrote the COVID-19 recovery model on April 7, 2020, and retired it on Dec. 9, 2020. By that time, the upfront recovery phase was done, and I needed to model out when we would get the jobs lost back.

2. Early in the labor market recovery, when we saw weaker job reports, I doubled and tripled down on my assertion that job openings would get to 10 million in this recovery. Job openings rose as high as to 12 million and are currently over 9 million. Even with the massive miss on a job report in May 2021, I didn’t waver.

Currently, the jobs openings, quit percentage and hires data are below pre-COVID-19 levels, which means the labor market isn’t as tight as it once was, and this is why the employment cost index has been slowing data to move along the quits percentage.

3. I wrote that we should get back all the jobs lost to COVID-19 by September of 2022. At the time this would be a speedy labor market recovery, and it happened on schedule, too

Total employment data

4. This is the key one for right now: If COVID-19 hadn’t happened, we would have between 157 million and 159 million jobs today, which would have been in line with the job growth rate in February 2020. Today, we are at 157,808,000. This is important because job growth should be cooling down now. We are more in line with where the labor market should be when averaging 140K-165K monthly. So for now, the fact that we aren’t trending between 140K-165K means we still have a bit more recovery kick left before we get down to those levels.

From BLS: Total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 275,000 in February, and the unemployment rate increased to 3.9 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Job gains occurred in health care, in government, in food services and drinking places, in social assistance, and in transportation and warehousing.

Here are the jobs that were created and lost in the previous month:

In this jobs report, the unemployment rate for education levels looks like this:

- Less than a high school diploma: 6.1%

- High school graduate and no college: 4.2%

- Some college or associate degree: 3.1%

- Bachelor’s degree or higher: 2.2%

Today’s report has continued the trend of the labor data beating my expectations, only because I am looking for the jobs data to slow down to a level of 140K-165K, which hasn’t happened yet. I wouldn’t categorize the labor market as being tight anymore because of the quits ratio and the hires data in the job openings report. This also shows itself in the employment cost index as well. These are key data lines for the Fed and the reason we are going to see three rate cuts this year.

recession unemployment covid-19 fed federal reserve mortgage rates recession recovery unemploymentUncategorized

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Inside The Most Ridiculous Jobs Report In History: Record 1.2 Million Immigrant Jobs Added In One Month

Last month we though that the January…

Last month we though that the January jobs report was the "most ridiculous in recent history" but, boy, were we wrong because this morning the Biden department of goalseeked propaganda (aka BLS) published the February jobs report, and holy crap was that something else. Even Goebbels would blush.

What happened? Let's take a closer look.

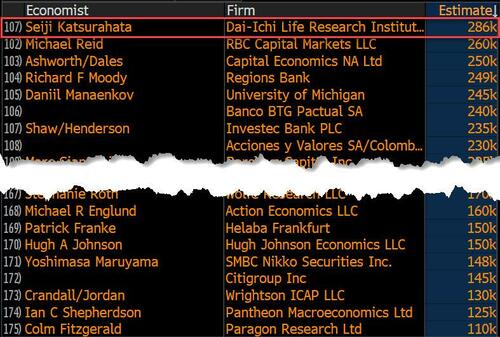

On the surface, it was (almost) another blockbuster jobs report, certainly one which nobody expected, or rather just one bank out of 76 expected. Starting at the top, the BLS reported that in February the US unexpectedly added 275K jobs, with just one research analyst (from Dai-Ichi Research) expecting a higher number.

Some context: after last month's record 4-sigma beat, today's print was "only" 3 sigma higher than estimates. Needless to say, two multiple sigma beats in a row used to only happen in the USSR... and now in the US, apparently.

Before we go any further, a quick note on what last month we said was "the most ridiculous jobs report in recent history": it appears the BLS read our comments and decided to stop beclowing itself. It did that by slashing last month's ridiculous print by over a third, and revising what was originally reported as a massive 353K beat to just 229K, a 124K revision, which was the biggest one-month negative revision in two years!

Of course, that does not mean that this month's jobs print won't be revised lower: it will be, and not just that month but every other month until the November election because that's the only tool left in the Biden admin's box: pretend the economic and jobs are strong, then revise them sharply lower the next month, something we pointed out first last summer and which has not failed to disappoint once.

In the past month the Biden department of goalseeking stuff higher before revising it lower, has revised the following data sharply lower:

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) August 30, 2023

- Jobs

- JOLTS

- New Home sales

- Housing Starts and Permits

- Industrial Production

- PCE and core PCE

To be fair, not every aspect of the jobs report was stellar (after all, the BLS had to give it some vague credibility). Take the unemployment rate, after flatlining between 3.4% and 3.8% for two years - and thus denying expectations from Sahm's Rule that a recession may have already started - in February the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 3.9%, the highest since February 2022 (with Black unemployment spiking by 0.3% to 5.6%, an indicator which the Biden admin will quickly slam as widespread economic racism or something).

And then there were average hourly earnings, which after surging 0.6% MoM in January (since revised to 0.5%) and spooking markets that wage growth is so hot, the Fed will have no choice but to delay cuts, in February the number tumbled to just 0.1%, the lowest in two years...

... for one simple reason: last month's average wage surge had nothing to do with actual wages, and everything to do with the BLS estimate of hours worked (which is the denominator in the average wage calculation) which last month tumbled to just 34.1 (we were led to believe) the lowest since the covid pandemic...

... but has since been revised higher while the February print rose even more, to 34.3, hence why the latest average wage data was once again a product not of wages going up, but of how long Americans worked in any weekly period, in this case higher from 34.1 to 34.3, an increase which has a major impact on the average calculation.

While the above data points were examples of some latent weakness in the latest report, perhaps meant to give it a sheen of veracity, it was everything else in the report that was a problem starting with the BLS's latest choice of seasonal adjustments (after last month's wholesale revision), which have gone from merely laughable to full clownshow, as the following comparison between the monthly change in BLS and ADP payrolls shows. The trend is clear: the Biden admin numbers are now clearly rising even as the impartial ADP (which directly logs employment numbers at the company level and is far more accurate), shows an accelerating slowdown.

But it's more than just the Biden admin hanging its "success" on seasonal adjustments: when one digs deeper inside the jobs report, all sorts of ugly things emerge... such as the growing unprecedented divergence between the Establishment (payrolls) survey and much more accurate Household (actual employment) survey. To wit, while in January the BLS claims 275K payrolls were added, the Household survey found that the number of actually employed workers dropped for the third straight month (and 4 in the past 5), this time by 184K (from 161.152K to 160.968K).

This means that while the Payrolls series hits new all time highs every month since December 2020 (when according to the BLS the US had its last month of payrolls losses), the level of Employment has not budged in the past year. Worse, as shown in the chart below, such a gaping divergence has opened between the two series in the past 4 years, that the number of Employed workers would need to soar by 9 million (!) to catch up to what Payrolls claims is the employment situation.

There's more: shifting from a quantitative to a qualitative assessment, reveals just how ugly the composition of "new jobs" has been. Consider this: the BLS reports that in February 2024, the US had 132.9 million full-time jobs and 27.9 million part-time jobs. Well, that's great... until you look back one year and find that in February 2023 the US had 133.2 million full-time jobs, or more than it does one year later! And yes, all the job growth since then has been in part-time jobs, which have increased by 921K since February 2023 (from 27.020 million to 27.941 million).

Here is a summary of the labor composition in the past year: all the new jobs have been part-time jobs!

But wait there's even more, because now that the primary season is over and we enter the heart of election season and political talking points will be thrown around left and right, especially in the context of the immigration crisis created intentionally by the Biden administration which is hoping to import millions of new Democratic voters (maybe the US can hold the presidential election in Honduras or Guatemala, after all it is their citizens that will be illegally casting the key votes in November), what we find is that in February, the number of native-born workers tumbled again, sliding by a massive 560K to just 129.807 million. Add to this the December data, and we get a near-record 2.4 million plunge in native-born workers in just the past 3 months (only the covid crash was worse)!

The offset? A record 1.2 million foreign-born (read immigrants, both legal and illegal but mostly illegal) workers added in February!

Said otherwise, not only has all job creation in the past 6 years has been exclusively for foreign-born workers...

... but there has been zero job-creation for native born workers since June 2018!

This is a huge issue - especially at a time of an illegal alien flood at the southwest border...

... and is about to become a huge political scandal, because once the inevitable recession finally hits, there will be millions of furious unemployed Americans demanding a more accurate explanation for what happened - i.e., the illegal immigration floodgates that were opened by the Biden admin.

Which is also why Biden's handlers will do everything in their power to insure there is no official recession before November... and why after the election is over, all economic hell will finally break loose. Until then, however, expect the jobs numbers to get even more ridiculous.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex