Bitcoin Is Global Money For An Interconnected World

Globalization has occurred to people, products and corporations — but what about our money?

Globalization has occurred to people, products and corporations — but what about our money?

Globalization + What Is Money = Bitcoin

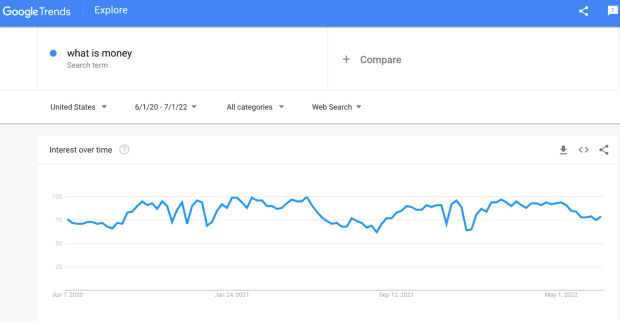

What is money? It's one of the more popular questions of the last few years. Especially in 2020 and 2021, when the grand, new U.S. administration decided to act as if a drunken sailor had taken over the keys to the printing press.

“You get money, you get money, and you get …” CTRL+P … CTRL+P … CTRL+P …

So — what is money?

It’s a question I asked early in my journey that started in the depths of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). I asked this question for years before and after the infamous month of September 2008, when the global financial system ground to a halt.

Bank Runs And Liquidity Crises

A historic day, September 16, 2008, the day of the breaking of the buck … The day when global money market funds were no longer worth a dollar due to a liquidity crunch manufactured by the world's most prominent banks, corporations, hedge funds, elites and global financiers — a crunch precipitated by professionals, not retail.

The systemic plumbing was frozen. Since May, the cryptocurrency ecosystem has been facing its own liquidity crisis.

This new digital asset class consists of many new and naive players, many who’ve never seen what happens when financial plumbing freezes. Pain has been felt and narratives have been shattered as the meltdown and deleveraging moved across the intertwined system. The market is taking no prisoners, much the same way it always does in the traditional financial system. Leverage and greed are a double-edged sword. The two have no mercy on anyone in their path. No player goes unscathed. Neither did bitcoin or traditional markets as the spillover from leverage and degen trading made its way across the globe, one financial participant and asset at a time.

So, we sit here, facing our first real and broad liquidity crisis in Bitcoin.

This is a crisis precipitated by greed, exposed by Terra/LUNA’s algorithm which attempted to codify the behaviors and role of the Federal Reserve Board. Through these mechanisms we learned they provided a facility for ex-Wall Street sharks to target as they swam amongst cryptocurrency liquidity pools, exchanges, and newly-formed cryptocurrency hedge funds.

Some things never change … even if money tries to.

Greed is hard to avoid and hides in plain sight under the names of yield, credit, lending and arbitrage.

We watch headlines one after another as they announce the failure or merger of major “decentralized” cryptocurrency institutions. As they crumble we realize many of these “over-collateralized” lenders and loans may have just been another alias for greed — the very thing Bitcoin and its 21 million impenetrable units are supposed to help fix, but in the end did not.

What we found is that the money might be different, but individuals and institutions are the same.

I guess there really are wolves in sheep’s clothes?

What we found is that education matters. An education on money is still sorely needed before Bitcoin and money are ready for globalization!

Monetary Crises Are Not New

The psychology and behavior of these events are typically the same. Whether it’s 1873, 1893, 1907, 1929-1933, 2000, 2007, or 2020. It always feels much like it does now — the hype, the hysteria, then the disbelief as the dominoes fall.

Some have seen it before and some are finding out for the first time what it really means to be leveraged, experiencing the pain of receiving a margin call.

We are finding that contagion can reach Bitcoin even if it stems from the broader "cryptocurrency" ecosystem, as many believe. We're finding out that boomers and their rocks may be jaded, but may also not be totally wrong. Every narrative is part truth and part marketing. In challenging times, you find out which is which.

Through pain is learning. Through pain there is education. It comes with a degree from the school of hard knocks.

Money made easily, goes easily.

Yield that sounds unreal, is unreal. It’s just a matter of time.

That’s the first grade lesson the community learned. One collateral asset plus a borrowed collateral asset is not equal to to 20% risk-free yield. Some, unfortunately, will repeat first grade. Others will move on.

Preparing To Be Globalized Money

The entire digital asset class is facing its first real test as it prepares to become global money. We globalized people in the early 1900s, we globalized corporations and products in the 1980s and 90s, but we’ve still yet to globalize money. Until the globalization of money happens we can’t efficiently move people, products and money throughout the system.

What we learn from this event, from this bear market in bitcoin, will help lead towards the globalization of money, completing the triangle of people, products and money.

The same tests were taken by corporations, manufacturers and the travel industry as they prepared to move people, products and corporations around the world. So, now it’s time for money to stand up and take these tests as well.

Bitcoin needs to prove it’s ready to be a global money; to prove it’s ready for mass adoption.

This test proved you can’t lose sight of the meaning of having a low time-preference. This test proved you can’t have 100:1 leverage, why rehypothecation is bad and why even getting involved in an innocent attraction to yield can get messy, really quick.

Not your keys, not your coins just became, “Hand over your keys, hand over your coins.”

Given the amount of leverage wiped out, we know there were more wearing the not-your-keys t-shirts than there were practicing what they preached. Today, and for the past month or two, individuals are no longer asking, “What is money?” They are asking:

- Where is my money?

- What about that yield you promised?

- What is rehypothecation?

- Why, why why?

The short answer is greed.

As the 21st century nears being already a quarter behind us, it feels like a good time to reflect on where we are, where we’ve been, and where we’re headed. To do so, it requires reflecting on globalization: what that means, what its impact has been, and what it hasn’t achieved.

The Global Economy Is Integrated, But Money Is Not

This is the opportunity.

When referring to globalization, there’s no time like the present to quote our friends (below) at the World Economic Forum (WEF) on the definition of globalization.

Why? Shouldn’t we be running to the hills away from this group?

Didn’t they cause the destruction?

Didn’t they contribute to the mass psychosis of the last few years?

Aren’t they part of the conspiracy the anons are against?

Frankly … who knows? I’ll let you decide. They know. We don’t.

They’ll have to answer to the man upstairs at the pearly gates. Believers won’t have to answer for them.

All we can do is gather information that matters — to us, our families, our neighbors, our communities and the things that happen within the four walls of our own households. What matters is that money is being globalized as we speak. What matters is that the opportunity at hand is to be part of the globalization of money, to bring it inline with the movement of people and corporate products.

On the other side of this liquidity crisis will be a world that operates for the first time in a truly global nature. One where people, corporations, products and money flow seamlessly across the rails of the internet as needed and when needed.

So, according to the WEF, globalization is

“In simple terms, globalization is the process by which people and goods move easily across borders. Principally, it's an economic concept – the integration of markets, trade and investments with few barriers to slow the flow of products and services between nations. There is also a cultural element, as ideas and traditions are traded and assimilated.

Globalization has brought many benefits to many people. But not to everyone.”

Let’s rewrite this a little. In simple terms, the opportunity is to globalize money so that it can move as easily across borders as people and goods, so that few barriers slow the flow of money between nations, people, products and services. The opportunity is to connect ideas and integrate traditions so that money can be traded and assimilated in manners that match and are globalized in a way that brings benefit to many, but more importantly, to everyone.

This is what the WEF, Bank of International Settlements (BIS), International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and central banks preach but DO NOT practice with their siloed, self-serving non-globalized money. The opportunity is to introduce change.

My thoughts were stirred by Lawrence Lepard’s (@LawrencLepard) comment on a Twitter post by Otavio Costa (@TaviCosta).

The point conveyed is how the global economy is interconnected. An interconnected economic system is a good thing.

However, given the structure of how money flows through the system it doesn’t support the global nature of our people, products and corporations.

After the “COVID-19” meltdown of 2020 and the supply chain disruptions of 2021/22, it’s become apparent as to what the real problem is:

Yes, the global economy is interconnected BUT global money is NOT.

This presents a challenge for the way people want to move about the globe and how they need to pay for things. In the 20th century, we experienced globalization of people, products and corporations. The Bretton Woods (BW) agreement of 1944 initiated this movement, but was not successful in the globalization of money. Bretton Woods was an attempt to move from a fixed-rate gold system to a dollar-pegged fiat system, though it began to falter only a couple of decades after.

Living Out Triffin’s Dilemma

The benefit of Bretton Woods was that it paved the way for globalizing corporate products and business in a manner that matched the flow of people moving around the globe. The downside was that the system didn’t really solve the main problem of providing money that was truly global in nature. Though a new system, it still suffered the same problem of not being global. As such, it succumbed to Triffin’s dilemma.

“... the Bretton Woods system contained an inherent and potentially fatal flaw in its dependence on the dollar. … the volume of trade expanded over time, any fixed exchange rate system would need an increase in usable reserves, in other words, an increase in acceptable international money to finance increased trade and investment.* Future gold production at the established price could not be enough to meet the need, so the source of the international liquidity necessary to lubricate growth within the Bretton Woods system would have to be dollars …

“If the U.S. deficits continued, confidence in the dollar and eventually the system would be undermined, and the result would be instability. But if the U.S. deficits were eliminated, the rest of the world would be deprived of the dollars it needed to build up its reserves and finance economic growth. For countries other than the United States, the question later became stark: hold more dollars in their reserves or turn them in for more gold from the United States. The latter course, probably sooner rather than later, would force the United States to stop selling gold, one of the foundations of the system. The former course of holding an increasing amount of dollars would inexorably undermine confidence as the potential demands on our gold stock came to far exceed the amount available to meet them. Either course contained the seeds of its own disaster.”

Source: Changing Fortunes by Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten

*Personal note: we tried to solve this with eurodollars.

In an attempt to combat this, during the 1960s and 70s, the Group of Five (G5) was created out of meetings by a select few that ultimately built international relationships to determine the pecking order underneath the U.S. hedgemon. They decided who would devalue, who would inflate and who would seek help through loans from the IMF and World Bank. These self-defined committees weren’t originally official in capacity, but are today what we refer to as the Group of Seven (G7), G8 and G10 — the groups that meet but appear to have increasinglyly taken direction from the Bank For International Settlements (BIS), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank as to how the global financial system should and will operate.*

*Interpretation source: Changing Fortunes by Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten

As signs of trouble arose under Bretton Woods, it was determined that lack of reserves was the issue more than lack of money, as reserves would allow an extension of more money than just money itself. So, in 1969 the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) were set up as an international reserve asset. SDRs, in theory, would broaden the burden of one country being the global reserve, removing the nth currency problem. It was considered a digital asset that was a basket of the major global currencies of that time (USD, euro, yen, British pound, and the yuan as of October 2016). SDRs are held by countries and aren’t usable by individuals or private parties. Technically, SDRs were digital money, but they did not function as such because they lacked monetary and communication technology — two critical inputs that are now available in the 21st century.

“... he [secretary Henry Fowler] had succeeded in obtaining agreement on the creation of Special Drawing Rights, or SDRs, at the annual IMF meeting in Rio de Janeiro in September of 1967. Great hopes were placed on the imaginative new instrument, which promptly was labeled “paper gold” but was neither paper nor gold; as one wit at the IMF said, the SDR was “not minted, not printed.” Rather, the SDR could be found only in the blips on an IMF computer, and many restrictions were placed on activating the computer. … The financial markets viewed it as something of a synthetic creation that was not really as good as gold or the dollar.”

Source: “Changing Fortunes” by Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten

In 2022, we are acutely aware and understand the ramifications of globalization without globalized money.

Now, we have the capability and monetary technologies in place. Now, we have true digital currencies. Digital currencies that are more than blips on an IMF computer. Now, we have the Bitcoin network. Now, we have the ability to globalize money.

But, do we have the global leaders to implement it? Are there leaders of countries who are more interested in producing sound money and less interested in battling for power and control during a time when our world order is seemingly up for grabs? Will the New World Order redefine money on a sound basis?

“At one point, my French colleague [Claude Brossolette] drew a little triangle on a piece of paper to illustrate what he considered the three ways of designing a monetary system. One one side of the triangle he wrote ‘Dominant Country’ or ‘Hedgemonic Power’ – I don’t remember the precise phrase. Underneath it he wrote ‘tyrant’. He said, ‘We don’t want that.’ On another side of the triangle he wrote ‘Dispersed Power,’ and underneath that he wrote ‘chaos.’ ‘We don’t want that.’ And that left only the base of the triangle, where he also wrote ‘Dominant Power.” But underneath that he wrote ‘benign.’

“I think he meant the United States had been relatively benign, and the system had worked.”

Source: “Changing Fortunes” by Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten

Through decades of financial trial and error, banking panics, liquidity crises and geopolitical feuds we’ve come to understand that centralized money is a neverending financial war: a war precipitated by a few men and women and a handful of committees and central banks around the world — all centralized and all with their own self-serving interests.

In the United States, these financial battles began in the mid-1800s with wildcat banking and led to the Panic of 1907. This last event gave rise to the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913, which was ultimately the outcome of similar but competing plans from Democrats (the Federal Reserve Act) and Republicans (the Aldrich Plan).

“The presidential campaign of 1912 records one of the more interesting political upsets in American history. The incumbent, Willam Howard Taft, was a popular president, and the Republicans, in a period of general prosperity, were firmly in control of the government through a Republican majority in both houses. The Democratic challenger Woodrow Wilson, Governor of New Jersey, had no national recognition, and was a stiff, austere man who excited little public support. Both parties included a monetary reform bill in their platforms: The Republicans were committed to the Aldrich Plan, which had been denounced as a Wall Street plan, and the Democrats the Federal Reserve Act. Neither party bothered to inform the public that the bills were almost identical except for the names. … since the bankers were financing all three candidates, they would win regardless of the outcome.”

Source: “The Secrets Of The Federal Reserve” by Eustace Mullins

After decades of Federal Reserve rule and improvements under the Bretton Woods system, we did have a broader and more diverse economic system, but also one that isn’t lasting. In short order, the new system (BW) began to falter in the 1960s and 70s and these uncorrected errors defined by the IMF and BIS still plague us today, after five decades of kicking the can down the road.

It is now clear that the lack of technology was the cause of the demise that led to the introduction of the petrodollar and the removal of the gold standard in 1971.

Global finance ministers were well aware because the system was breaking in the 1960s and 70s. They were bound by long plane flights and months of committee meetings — bound in a period when time was of utmost importance as it related to currency market turbulence; a time when the gold standard was removed, because no party was willing to relinquish monetary power at the expense of their country’s currency over another. In those days, the solutions were there but they required more technology than financial markets had access to.

“Organizational and institutional development is not, of course, a substitute for action, and the early Kennedy years saw a lot of technical innovation. For one thing, the United States began intervening in the foreign exchange markets, ending the taboo on such operations that had prevailed for many years. Partly as a means of acquiring resources for intervention, a “swap network” was established. That was a technique for prearranging short-term lines of credit among the major central banks and treasuries, enabling them to borrow each other’s currency almost instantaneously in the time of need.”

Source: “Changing Fortunes” by Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten

Today, both on the monetary and communications front we have solutions for these problems.

They are driven by the power of the internet and new telecommunications towers.

In the past, the creation and maintenance of international relationships required days of travel or months of tireless committee meetings all over the world. The findings had to be brought back to each country and rehashed again. Now, much of that leg work can be replaced by instant global communication via mobile phone, text, email, chat and platforms like Zoom that offer video for more formal meeting purposes. Today’s technology immensely increases the ability to solve monetary problems and create policies quickly with real-time information and data access. Today, we can move in the direction of monetary communication and money that benefits all in a better means than in the past.

On the money front, we now have the Bitcoin network to act as a digital collateral asset, much like SDRs were intended.

As serious troubles within the monetary system arose, in the 60s and 70s countries began playing economic games in currency markets. It was a race to devalue in order to compete, a race that only put more pressure on an illiquid, disjointed, and fragile system.

Focus On The Home Front Or The Frontier?

For the U.S., there was a growing economic struggle to maintain and balance the needs at home with the needs of the world. It was becoming too much for one country. It was proving what Triffin had warned of. Once again, countries were beginning to sour on the benefits to the United States on their behalf. At the time, many international players were more open to a floating rate system as it would allow each to take care of themselves at home, though it may cause issues to the growing globalized economy of products and people. Today’s technology is better suited for exactly these types of globalized floating-rate monetary systems, encompassing networks involving Bitcoin, stablecoins and a host of other monetary technologies that can allow for the globalization of money.

Looking back, the SDR (sometimes called XDR) probably was the best solution conceivable at the time, but it was stymied by the fact that we didn’t have the technology to make it work.

“One reason XDRs may not see much use as foreign exchange reserve assets is that they must be exchanged into a currency before use.[5] This is due in part to the fact private parties do not hold XDRs:[5] they are only used and held by IMF member countries, the IMF itself, and a select few organizations licensed to do so by the IMF … This fact has led the IMF to label the XDR as an "imperfect reserve asset".[22]

“Another reason they may see little use is that the number of XDRs in existence is relatively few … To function well a foreign exchange reserve asset must have sufficient liquidity, but XDRs, because of their small number, may be perceived to be an illiquid asset. The IMF says, "expanding the volume of official XDRs is a prerequisite for them to play a more meaningful role as a substitute reserve asset.[23]”

Mid-to-late 20th century, countries were beginning to awaken to the benefit the United States gained from having the global reserve currency in U.S. dollars.

“On February 4, 1965, de Gaulle [President of France] took the opportunity of one of his staged press conferences to begin an open attack. His basic argument was that the ‘dollar system’ provided the United States with an ‘exorbitant privilege.’ It was able freely to finance itself around the world, because unlike other countries its balance of payments deficits did not lead to loss of reserves but could be settled in dollars without limit. The solution would be to go back to the gold standard, and the language was arresting. The time had come, de Gaulle said, to establish the international system ‘on an unquestionable basis that does not bear the stamp of any one country in particular.’ ”

Source: “Changing Fortunes” by Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten

It was recognized that new agreements were required. In those days, as a means to compete, others began the process of devaluing their currency in an attempt to gain global market share of power. Ultimately, the U.S. was boxed in. The world couldn’t survive if the United States didn’t maintain deficits and the U.S. couldn’t survive if others came requesting gold for their dollar reserves.

“In early 1962, in response to a Treasury initiative, the ten most important financial powers joined together in agreeing to backstop the International Monetary Fund with a credit line of $6 billion … The mechanism was called the General Arrangements to Borrow. [GAB] …

"While there was no clear intention of American draw on the IMF, the new agreements demonstrated that substantial funds could be marshaled to meet a speculative attack on the dollar without forcing the United States to sell large amounts of gold. We also did not want other countries to find themselves suddenly short of liquidity and forced into devaluation, which would undercut our competitive position.”

Source: :Changing Fortunes” by Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten

(Note: I’ve added bold to denote the real desires and competitive advantages that were overlooked by other countries.)

At the time, the internet was non-existent. Today, it connects the globe.

There wasn’t a means to move a digital asset like the SDR around the globe. Today, there is the Bitcoin network, and it offers many more decimals or fractions to help with the prior liquidity limitations of money. Additionally, a modern monetary network like Bitcoin offers the ability to integrate with existing, new and future monetary networks in ways that today’s networks and those of the past could not — all because it’s internet operated and money built for interoperability.

We have the tools and technology to solve the problems that plagued past financial systems. We have digital money and are building out more integrated monetary networks and monetary technologies that provide the seamless requirements so that the globalization of money can happen for the first time.

The Globalization Of Money

As money approaches its day in the spotlight of disruption, its day to become globalized, then we should be able to better achieve the ideals and benefits of floating rate exchange.

The globalization of money should allow each economy to have their own money — a form of money that fits their own needs, but is easily convertible at a cheap rate to a base-layer money a la bitcoin. Then, it can convert into whatever end currency is needed to complete the task at hand. All in a cheap, quick, and instantly settleable nature. These were the ideals of a base currency like SDRs and now we have a proven digital collateral asset like bitcoin that could make it work.

As we’re nearly a quarter of the way through the 21st century, we finally have the technology that allows for globalization of money. So now, we can have a truly global economy:

- Where people have the opportunity to move freely around the globe.

- Where corporations and products have the opportunity to move freely around the globe.

- Where MONEY has the freedom to move freely around the globe.

All in a way that works for all, not for one or a few.

As we move past this recent liquidity crisis caused by the cryptocurrency crash I think we’ll find that through experimentation and adoption the new global digital rails will be better suited to finalize the integration of people, business, and money.

It turns out that what we’ve called globalization, was not that at all.

Just as in the 1970s, if the United States decided not to play ball the economic system would have shut down, penalizing everyone. In 2020 we found that we have a one-way network of goods from primarily a single source, meaning that if China decides to shut down, then the world comes to a grinding halt and prices increase sharply as inflation takes hold. Much the same in 1912, if the Titanic or other ships crashed, the movement of people and goods around the globe was hindered.

Every few decades we’ve had advances in technology that brought forth another leg of support for globalization.

Now, we can finally have all three in place: people, business and money.

After this liquidity crisis, builders will finalize the new internet rails that will allow value to flow seamlessly around the globe, just as information, email, content, news, e-commerce and music currently do. That’s the power of internet money. That’s the power of programmable money.

When people are able to communicate money seamlessly the next wave of internet innovation will continue to drive the globe to new heights.

This is a guest post by Kane McGukin. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.

Opinions expressed in this article are not to be considered investment advice. Past performance is not indicative of future performance as all investments carry risk including potential loss of principle.

cryptocurrency bitcoin btc covid-19 currencies pound euro yuan goldGovernment

Vaccine-skeptical mothers say bad health care experiences made them distrust the medical system

Vaccine skepticism, and the broader medical mistrust and far-reaching anxieties it reflects, is not just a fringe position in the 21st century.

Why would a mother reject safe, potentially lifesaving vaccines for her child?

Popular writing on vaccine skepticism often denigrates white and middle-class mothers who reject some or all recommended vaccines as hysterical, misinformed, zealous or ignorant. Mainstream media and medical providers increasingly dismiss vaccine refusal as a hallmark of American fringe ideology, far-right radicalization or anti-intellectualism.

But vaccine skepticism, and the broader medical mistrust and far-reaching anxieties it reflects, is not just a fringe position.

Pediatric vaccination rates had already fallen sharply before the COVID-19 pandemic, ushering in the return of measles, mumps and chickenpox to the U.S. in 2019. Four years after the pandemic’s onset, a growing number of Americans doubt the safety, efficacy and necessity of routine vaccines. Childhood vaccination rates have declined substantially across the U.S., which public health officials attribute to a “spillover” effect from pandemic-related vaccine skepticism and blame for the recent measles outbreak. Almost half of American mothers rated the risk of side effects from the MMR vaccine as medium or high in a 2023 survey by Pew Research.

Recommended vaccines go through rigorous testing and evaluation, and the most infamous charges of vaccine-induced injury have been thoroughly debunked. How do so many mothers – primary caregivers and health care decision-makers for their families – become wary of U.S. health care and one of its most proven preventive technologies?

I’m a cultural anthropologist who studies the ways feelings and beliefs circulate in American society. To investigate what’s behind mothers’ vaccine skepticism, I interviewed vaccine-skeptical mothers about their perceptions of existing and novel vaccines. What they told me complicates sweeping and overly simplified portrayals of their misgivings by pointing to the U.S. health care system itself. The medical system’s failures and harms against women gave rise to their pervasive vaccine skepticism and generalized medical mistrust.

The seeds of women’s skepticism

I conducted this ethnographic research in Oregon from 2020 to 2021 with predominantly white mothers between the ages of 25 and 60. My findings reveal new insights about the origins of vaccine skepticism among this demographic. These women traced their distrust of vaccines, and of U.S. health care more generally, to ongoing and repeated instances of medical harm they experienced from childhood through childbirth.

As young girls in medical offices, they were touched without consent, yelled at, disbelieved or threatened. One mother, Susan, recalled her pediatrician abruptly lying her down and performing a rectal exam without her consent at the age of 12. Another mother, Luna, shared how a pediatrician once threatened to have her institutionalized when she voiced anxiety at a routine physical.

As women giving birth, they often felt managed, pressured or discounted. One mother, Meryl, told me, “I felt like I was coerced under distress into Pitocin and induction” during labor. Another mother, Hallie, shared, “I really battled with my provider” throughout the childbirth experience.

Together with the convoluted bureaucracy of for-profit health care, experiences of medical harm contributed to “one million little touch points of information,” in one mother’s phrase, that underscored the untrustworthiness and harmful effects of U.S. health care writ large.

A system that doesn’t serve them

Many mothers I interviewed rejected the premise that public health entities such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration had their children’s best interests at heart. Instead, they tied childhood vaccination and the more recent development of COVID-19 vaccines to a bloated pharmaceutical industry and for-profit health care model. As one mother explained, “The FDA is not looking out for our health. They’re looking out for their wealth.”

After ongoing negative medical encounters, the women I interviewed lost trust not only in providers but the medical system. Frustrating experiences prompted them to “do their own research” in the name of bodily autonomy. Such research often included books, articles and podcasts deeply critical of vaccines, public health care and drug companies.

These materials, which have proliferated since 2020, cast light on past vaccine trials gone awry, broader histories of medical harm and abuse, the rapid growth of the recommended vaccine schedule in the late 20th century and the massive profits reaped from drug development and for-profit health care. They confirmed and hardened women’s suspicions about U.S. health care.

The stories these women told me add nuance to existing academic research into vaccine skepticism. Most studies have considered vaccine skepticism among primarily white and middle-class parents to be an outgrowth of today’s neoliberal parenting and intensive mothering. Researchers have theorized vaccine skepticism among white and well-off mothers to be an outcome of consumer health care and its emphasis on individual choice and risk reduction. Other researchers highlight vaccine skepticism as a collective identity that can provide mothers with a sense of belonging.

Seeing medical care as a threat to health

The perceptions mothers shared are far from isolated or fringe, and they are not unreasonable. Rather, they represent a growing population of Americans who hold the pervasive belief that U.S. health care harms more than it helps.

Data suggests that the number of Americans harmed in the course of treatment remains high, with incidents of medical error in the U.S. outnumbering those in peer countries, despite more money being spent per capita on health care. One 2023 study found that diagnostic error, one kind of medical error, accounted for 371,000 deaths and 424,000 permanent disabilities among Americans every year.

Studies reveal particularly high rates of medical error in the treatment of vulnerable communities, including women, people of color, disabled, poor, LGBTQ+ and gender-nonconforming individuals and the elderly. The number of U.S. women who have died because of pregnancy-related causes has increased substantially in recent years, with maternal death rates doubling between 1999 and 2019.

The prevalence of medical harm points to the relevance of philosopher Ivan Illich’s manifesto against the “disease of medical progress.” In his 1982 book “Medical Nemesis,” he insisted that rather than being incidental, harm flows inevitably from the structure of institutionalized and for-profit health care itself. Illich wrote, “The medical establishment has become a major threat to health,” and has created its own “epidemic” of iatrogenic illness – that is, illness caused by a physician or the health care system itself.

Four decades later, medical mistrust among Americans remains alarmingly high. Only 23% of Americans express high confidence in the medical system. The United States ranks 24th out of 29 peer high-income countries for the level of public trust in medical providers.

For people like the mothers I interviewed, who have experienced real or perceived harm at the hands of medical providers; have felt belittled, dismissed or disbelieved in a doctor’s office; or spent countless hours fighting to pay for, understand or use health benefits, skepticism and distrust are rational responses to lived experience. These attitudes do not emerge solely from ignorance, conspiracy thinking, far-right extremism or hysteria, but rather the historical and ongoing harms endemic to the U.S. health care system itself.

Johanna Richlin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

disease control extremism pandemic covid-19 vaccine treatment testing fda deathsGovernment

Is the National Guard a solution to school violence?

School board members in one Massachusetts district have called for the National Guard to address student misbehavior. Does their request have merit? A…

Every now and then, an elected official will suggest bringing in the National Guard to deal with violence that seems out of control.

A city council member in Washington suggested doing so in 2023 to combat the city’s rising violence. So did a Pennsylvania representative concerned about violence in Philadelphia in 2022.

In February 2024, officials in Massachusetts requested the National Guard be deployed to a more unexpected location – to a high school.

Brockton High School has been struggling with student fights, drug use and disrespect toward staff. One school staffer said she was trampled by a crowd rushing to see a fight. Many teachers call in sick to work each day, leaving the school understaffed.

As a researcher who studies school discipline, I know Brockton’s situation is part of a national trend of principals and teachers who have been struggling to deal with perceived increases in student misbehavior since the pandemic.

A review of how the National Guard has been deployed to schools in the past shows the guard can provide service to schools in cases of exceptional need. Yet, doing so does not always end well.

How have schools used the National Guard before?

In 1957, the National Guard blocked nine Black students’ attempts to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. While the governor claimed this was for safety, the National Guard effectively delayed desegregation of the school – as did the mobs of white individuals outside. Ironically, weeks later, the National Guard and the U.S. Army would enforce integration and the safety of the “Little Rock Nine” on orders from President Dwight Eisenhower.

One of the most tragic cases of the National Guard in an educational setting came in 1970 at Kent State University. The National Guard was brought to campus to respond to protests over American involvement in the Vietnam War. The guardsmen fatally shot four students.

In 2012, then-Sen. Barbara Boxer, a Democrat from California, proposed funding to use the National Guard to provide school security in the wake of the Sandy Hook school shooting. The bill was not passed.

More recently, the National Guard filled teacher shortages in New Mexico’s K-12 schools during the quarantines and sickness of the pandemic. While the idea did not catch on nationally, teachers and school personnel in New Mexico generally reported positive experiences.

Can the National Guard address school discipline?

The National Guard’s mission includes responding to domestic emergencies. Members of the guard are part-time service members who maintain civilian lives. Some are students themselves in colleges and universities. Does this mission and training position the National Guard to respond to incidents of student misbehavior and school violence?

On the one hand, New Mexico’s pandemic experience shows the National Guard could be a stopgap to staffing shortages in unusual circumstances. Similarly, the guards’ eventual role in ensuring student safety during school desegregation in Arkansas demonstrates their potential to address exceptional cases in schools, such as racially motivated mob violence. And, of course, many schools have had military personnel teaching and mentoring through Junior ROTC programs for years.

Those seeking to bring the National Guard to Brockton High School have made similar arguments. They note that staffing shortages have contributed to behavior problems.

One school board member stated: “I know that the first thought that comes to mind when you hear ‘National Guard’ is uniform and arms, and that’s not the case. They’re people like us. They’re educated. They’re trained, and we just need their assistance right now. … We need more staff to support our staff and help the students learn (and) have a safe environment.”

Yet, there are reasons to question whether calls for the National Guard are the best way to address school misconduct and behavior. First, the National Guard is a temporary measure that does little to address the underlying causes of student misbehavior and school violence.

Research has shown that students benefit from effective teaching, meaningful and sustained relationships with school personnel and positive school environments. Such educative and supportive environments have been linked to safer schools. National Guard members are not trained as educators or counselors and, as a temporary measure, would not remain in the school to establish durable relationships with students.

What is more, a military presence – particularly if uniformed or armed – may make students feel less welcome at school or escalate situations.

Schools have already seen an increase in militarization. For example, school police departments have gone so far as to acquire grenade launchers and mine-resistant armored vehicles.

Research has found that school police make students more likely to be suspended and to be arrested. Similarly, while a National Guard presence may address misbehavior temporarily, their presence could similarly result in students experiencing punitive or exclusionary responses to behavior.

Students deserve a solution other than the guard

School violence and disruptions are serious problems that can harm students. Unfortunately, schools and educators have increasingly viewed student misbehavior as a problem to be dealt with through suspensions and police involvement.

A number of people – from the NAACP to the local mayor and other members of the school board – have criticized Brockton’s request for the National Guard. Governor Maura Healey has said she will not deploy the guard to the school.

However, the case of Brockton High School points to real needs. Educators there, like in other schools nationally, are facing a tough situation and perceive a lack of support and resources.

Many schools need more teachers and staff. Students need access to mentors and counselors. With these resources, schools can better ensure educators are able to do their jobs without military intervention.

F. Chris Curran has received funding from the US Department of Justice, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, and the American Civil Liberties Union for work on school safety and discipline.

army governor pandemic mexicoGovernment

Chinese migration to US is nothing new – but the reasons for recent surge at Southern border are

A gloomier economic outlook in China and tightening state control have combined with the influence of social media in encouraging migration.

The brief closure of the Darien Gap – a perilous 66-mile jungle journey linking South American and Central America – in February 2024 temporarily halted one of the Western Hemisphere’s busiest migration routes. It also highlighted its importance to a small but growing group of people that depend on that pass to make it to the U.S.: Chinese migrants.

While a record 2.5 million migrants were detained at the United States’ southwestern land border in 2023, only about 37,000 were from China.

I’m a scholar of migration and China. What I find most remarkable in these figures is the speed with which the number of Chinese migrants is growing. Nearly 10 times as many Chinese migrants crossed the southern border in 2023 as in 2022. In December 2023 alone, U.S. Border Patrol officials reported encounters with about 6,000 Chinese migrants, in contrast to the 900 they reported a year earlier in December 2022.

The dramatic uptick is the result of a confluence of factors that range from a slowing Chinese economy and tightening political control by President Xi Jinping to the easy access to online information on Chinese social media about how to make the trip.

Middle-class migrants

Journalists reporting from the border have generalized that Chinese migrants come largely from the self-employed middle class. They are not rich enough to use education or work opportunities as a means of entry, but they can afford to fly across the world.

According to a report from Reuters, in many cases those attempting to make the crossing are small-business owners who saw irreparable damage to their primary or sole source of income due to China’s “zero COVID” policies. The migrants are women, men and, in some cases, children accompanying parents from all over China.

Chinese nationals have long made the journey to the United States seeking economic opportunity or political freedom. Based on recent media interviews with migrants coming by way of South America and the U.S.’s southern border, the increase in numbers seems driven by two factors.

First, the most common path for immigration for Chinese nationals is through a student visa or H1-B visa for skilled workers. But travel restrictions during the early months of the pandemic temporarily stalled migration from China. Immigrant visas are out of reach for many Chinese nationals without family or vocation-based preferences, and tourist visas require a personal interview with a U.S. consulate to gauge the likelihood of the traveler returning to China.

Social media tutorials

Second, with the legal routes for immigration difficult to follow, social media accounts have outlined alternatives for Chinese who feel an urgent need to emigrate. Accounts on Douyin, the TikTok clone available in mainland China, document locations open for visa-free travel by Chinese passport holders. On TikTok itself, migrants could find information on where to cross the border, as well as information about transportation and smugglers, commonly known as “snakeheads,” who are experienced with bringing migrants on the journey north.

With virtual private networks, immigrants can also gather information from U.S. apps such as X, YouTube, Facebook and other sites that are otherwise blocked by Chinese censors.

Inspired by social media posts that both offer practical guides and celebrate the journey, thousands of Chinese migrants have been flying to Ecuador, which allows visa-free travel for Chinese citizens, and then making their way over land to the U.S.-Mexican border.

This journey involves trekking through the Darien Gap, which despite its notoriety as a dangerous crossing has become an increasingly common route for migrants from Venezuela, Colombia and all over the world.

In addition to information about crossing the Darien Gap, these social media posts highlight the best places to cross the border. This has led to a large share of Chinese asylum seekers following the same path to Mexico’s Baja California to cross the border near San Diego.

Chinese migration to US is nothing new

The rapid increase in numbers and the ease of accessing information via social media on their smartphones are new innovations. But there is a longer history of Chinese migration to the U.S. over the southern border – and at the hands of smugglers.

From 1882 to 1943, the United States banned all immigration by male Chinese laborers and most Chinese women. A combination of economic competition and racist concerns about Chinese culture and assimilability ensured that the Chinese would be the first ethnic group to enter the United States illegally.

With legal options for arrival eliminated, some Chinese migrants took advantage of the relative ease of movement between the U.S. and Mexico during those years. While some migrants adopted Mexican names and spoke enough Spanish to pass as migrant workers, others used borrowed identities or paperwork from Chinese people with a right of entry, like U.S.-born citizens. Similarly to what we are seeing today, it was middle- and working-class Chinese who more frequently turned to illegal means. Those with money and education were able to circumvent the law by arriving as students or members of the merchant class, both exceptions to the exclusion law.

Though these Chinese exclusion laws officially ended in 1943, restrictions on migration from Asia continued until Congress revised U.S. immigration law in the Hart-Celler Act in 1965. New priorities for immigrant visas that stressed vocational skills as well as family reunification, alongside then Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s policies of “reform and opening,” helped many Chinese migrants make their way legally to the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s.

Even after the restrictive immigration laws ended, Chinese migrants without the education or family connections often needed for U.S. visas continued to take dangerous routes with the help of “snakeheads.”

One notorious incident occurred in 1993, when a ship called the Golden Venture ran aground near New York, resulting in the drowning deaths of 10 Chinese migrants and the arrest and conviction of the snakeheads attempting to smuggle hundreds of Chinese migrants into the United States.

Existing tensions

Though there is plenty of precedent for Chinese migrants arriving without documentation, Chinese asylum seekers have better odds of success than many of the other migrants making the dangerous journey north.

An estimated 55% of Chinese asylum seekers are successful in making their claims, often citing political oppression and lack of religious freedom in China as motivations. By contrast, only 29% of Venezuelans seeking asylum in the U.S. have their claim granted, and the number is even lower for Colombians, at 19%.

The new halt on the migratory highway from the south has affected thousands of new migrants seeking refuge in the U.S. But the mix of push factors from their home country and encouragement on social media means that Chinese migrants will continue to seek routes to America.

And with both migration and the perceived threat from China likely to be features of the upcoming U.S. election, there is a risk that increased Chinese migration could become politicized, leaning further into existing tensions between Washington and Beijing.

Meredith Oyen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

congress pandemic deaths south america mexico china-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized4 weeks ago

Uncategorized4 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoEyePoint poaches medical chief from Apellis; Sandoz CFO, longtime BioNTech exec to retire

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex