Uncategorized

Are We Living The Impact Of Mixing Business And Medicine?

Are We Living The Impact Of Mixing Business And Medicine?

Healthcare is starting to cost an arm and a leg, with U.S. spending reaching over 18% of GDP and rising. Maybe you’re thinking that doesn’t sound so high? That’s almost 10% more than healthcare spending for countries in the OECD. Healthcare has become so oppressively expensive that many are opting to abstain from care even when they need treatment, minorities and other vulnerable groups make up the majority of those affected. Now amid the Coronavirus crisis healthcare will be not only expensive but difficult to acquire because of quarantining measures and scarcity of supplies.

Q1 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Business or Medicine?

In recent years Americans have witnessed on average a 20% increase in their health spending, and that is only counting people with insurance. Those without may be spending even more, or worse, avoiding care completely. We have already seen such attempts to avoid or adapt treatment.

From 2009 to 2016 the cost of Epipens, a device that delivers a dose of epinephrine to manage the life-threatening effects of anaphylactic shock, grew from $100 to $600 causing some to hold on to old prescriptions past the point of expiration, or stop obtaining the life-saving drug altogether.

For those who face death without medicine, the costs are soaring. From 2012 to 2016 insulin prices caused diabetics to spend $2,841 more each year for treatment. There doesn’t seem to be relief in sight, with healthcare spending projected to reach $6 trillion a year by 2027.

Costs Less Known

The social costs of healthcare having a business bent are much higher than financial strains. Each year delaying or avoiding care leads to 125,000 avoidable deaths, with 26,000 dying due to lack of health insurance. The more vulnerable among the population suffer more deaths, making healthcare exceedingly more businesslike in ideology and approach, reducing people to probabilities and numbers. Nearly 9 in 10 of the uninsured are nonelderly adults, with minorities making up more than half of all uninsured.

The situation was dire for many before the onset of COVID-19, but now as the pandemic spreads, hospitals are dealing with critical shortages in equipment. Nearly 1 in 4 hospitals have fewer than 100 N95 masks on hand 1 in 5 hospitals report an immediate need for more ventilators In Feb. the FDA reported drug shortages related to Coronavirus. The strategic stockpile of N95 masks maintained by the federal government is also insufficient, with just 10.5 million of the estimated 300 million the country will need.

Healthcare has been under-serving some, now with difficulty abounding due to the Coronavirus, the system will have a hard time serving most.

Learn more about the social costs of mixing business and medicine below.

The post Are We Living The Impact Of Mixing Business And Medicine? appeared first on ValueWalk.

Uncategorized

Shipping company files surprise Chapter 7 bankruptcy, liquidation

While demand for trucking has increased, so have costs and competition, which have forced a number of players to close.

The U.S. economy is built on trucks.

As a nation we have relatively limited train assets, and while in recent years planes have played an expanded role in moving goods, trucks still represent the backbone of how everything — food, gasoline, commodities, and pretty much anything else — moves around the country.

Related: Fast-food chain closes more stores after Chapter 11 bankruptcy

"Trucks moved 61.1% of the tonnage and 64.9% of the value of these shipments. The average shipment by truck was 63 miles compared to an average of 640 miles by rail," according to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics 2023 numbers.

But running a trucking company has been tricky because the largest players have economies of scale that smaller operators don't. That puts any trucking company that's not a massive player very sensitive to increases in gas prices or drops in freight rates.

And that in turn has led a number of trucking companies, including Yellow Freight, the third-largest less-than-truckload operator; J.J. & Sons Logistics, Meadow Lark, and Boateng Logistics, to close while freight brokerage Convoy shut down in October.

Aside from Convoy, none of these brands are household names. but with the demand for trucking increasing, every company that goes out of business puts more pressure on those that remain, which contributes to increased prices.

Image source: Shutterstock

Another freight company closes and plans to liquidate

Not every bankruptcy filing explains why a company has gone out of business. In the trucking industry, multiple recent Chapter 7 bankruptcies have been tied to lawsuits that pushed otherwise successful companies into insolvency.

In the case of TBL Logistics, a Virginia-based national freight company, its Feb. 29 bankruptcy filing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Virginia appears to be death by too much debt.

"In its filing, TBL Logistics listed its assets and liabilities as between $1 million and $10 million. The company stated that it has up to 49 creditors and maintains that no funds will be available for unsecured creditors once it pays administrative fees," Freightwaves reported.

The company's owners, Christopher and Melinda Bradner, did not respond to the website's request for comment.

Before it closed, TBL Logistics specialized in refrigerated and oversized loads. The company described its business on its website.

"TBL Logistics is a non-asset-based third-party logistics freight broker company providing reliable and efficient transportation solutions, management, and storage for businesses of all sizes. With our extensive network of carriers and industry expertise, we streamline the shipping process, ensuring your goods reach their destination safely and on time."

The world has a truck-driver shortage

The covid pandemic forced companies to consider their supply chain in ways they never had to before. Increased demand showed the weakness in the trucking industry and drew attention to how difficult life for truck drivers can be.

That was an issue HBO's John Oliver highlighted on his "Last Week Tonight" show in October 2022. In the episode, the host suggested that the U.S. would basically start to starve if the trucking industry shut down for three days.

"Sorry, three days, every produce department in America would go from a fully stocked market to an all-you-can-eat raccoon buffet," he said. "So it’s no wonder trucking’s a huge industry, with more than 3.5 million people in America working as drivers, from port truckers who bring goods off ships to railyards and warehouses, to long-haul truckers who move them across the country, to 'last-mile' drivers, who take care of local delivery."

The show highlighted how many truck drivers face low pay, difficult working conditions and, in many cases, crushing debt.

"Hundreds of thousands of people become truck drivers every year. But hundreds of thousands also quit. Job turnover for truckers averages over 100%, and at some companies it’s as high as 300%, meaning they’re hiring three people for a single job over the course of a year. And when a field this important has a level of job satisfaction that low, it sure seems like there’s a huge problem," Oliver shared.

The truck-driver shortage is not just a U.S. problem; it's a global issue, according to IRU.org.

"IRU’s 2023 driver shortage report has found that over three million truck driver jobs are unfilled, or 7% of total positions, in 36 countries studied," the global transportation trade association reported.

"With the huge gap between young and old drivers growing, it will get much worse over the next five years without significant action."

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

bankruptcy bankruptcies pandemic stocks commoditiesUncategorized

Wendy’s has a new deal for daylight savings time haters

The Daylight Savings Time promotion slashes prices on breakfast.

Daylight Savings Time, or the practice of advancing clocks an hour in the spring to maximize natural daylight, is a controversial practice because of the way it leaves many feeling off-sync and tired on the second Sunday in March when the change is made and one has one less hour to sleep in.

Despite annual "Abolish Daylight Savings Time" think pieces and online arguments that crop up with unwavering regularity, Daylight Savings in North America begins on March 10 this year.

Related: Coca-Cola has a new soda for Diet Coke fans

Tapping into some people's very vocal dislike of Daylight Savings Time, fast-food chain Wendy's (WEN) is launching a daylight savings promotion that is jokingly designed to make losing an hour of sleep less painful and encourage fans to order breakfast anyway.

Image source: Wendy's.

Promotion wants you to compensate for lost sleep with cheaper breakfast

As it is also meant to drive traffic to the Wendy's app, the promotion allows anyone who makes a purchase of $3 or more through the platform to get a free hot coffee, cold coffee or Frosty Cream Cold Brew.

More Food + Dining:

- Taco Bell menu tries new take on an American classic

- McDonald's menu goes big, brings back fan favorites (with a catch)

- The 10 best food stocks to buy now

Available during the Wendy's breakfast hours of 6 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. (which, naturally, will feel even earlier due to Daylight Savings), the deal also allows customers to buy any of its breakfast sandwiches for $3. Items like the Sausage, Egg and Cheese Biscuit, Breakfast Baconator and Maple Bacon Chicken Croissant normally range in price between $4.50 and $7.

The choice of the latter is quite wide since, in the years following the pandemic, Wendy's has made a concerted effort to expand its breakfast menu with a range of new sandwiches with egg in them and sweet items such as the French Toast Sticks. The goal was both to stand out from competitors with a wider breakfast menu and increase traffic to its stores during early-morning hours.

Wendy's deal comes after controversy over 'dynamic pricing'

But last month, the chain known for the square shape of its burger patties ignited controversy after saying that it wanted to introduce "dynamic pricing" in which the cost of many of the items on its menu will vary depending on the time of day. In an earnings call, chief executive Kirk Tanner said that electronic billboards would allow restaurants to display various deals and promotions during slower times in the early morning and late at night.

Outcry was swift and Wendy's ended up walking back its plans with words that they were "misconstrued" as an intent to surge prices during its most popular periods.

While the company issued a statement saying that any changes were meant as "discounts and value offers" during quiet periods rather than raised prices during busy ones, the reputational damage was already done since many saw the clarification as another way to obfuscate its pricing model.

"We said these menuboards would give us more flexibility to change the display of featured items," Wendy's said in its statement. "This was misconstrued in some media reports as an intent to raise prices when demand is highest at our restaurants."

The Daylight Savings Time promotion, in turn, is also a way to demonstrate the kinds of deals Wendy's wants to promote in its stores without putting up full-sized advertising or posters for what is only relevant for a few days.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024

stocks pandemicUncategorized

Comments on February Employment Report

The headline jobs number in the February employment report was above expectations; however, December and January payrolls were revised down by 167,000 combined. The participation rate was unchanged, the employment population ratio decreased, and the …

Prime (25 to 54 Years Old) Participation

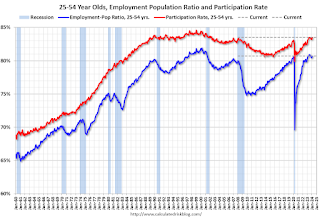

Since the overall participation rate is impacted by both cyclical (recession) and demographic (aging population, younger people staying in school) reasons, here is the employment-population ratio for the key working age group: 25 to 54 years old.

The 25 to 54 years old participation rate increased in February to 83.5% from 83.3% in January, and the 25 to 54 employment population ratio increased to 80.7% from 80.6% the previous month.

Average Hourly Wages

The graph shows the nominal year-over-year change in "Average Hourly Earnings" for all private employees from the Current Employment Statistics (CES).

The graph shows the nominal year-over-year change in "Average Hourly Earnings" for all private employees from the Current Employment Statistics (CES). Wage growth has trended down after peaking at 5.9% YoY in March 2022 and was at 4.3% YoY in February.

Part Time for Economic Reasons

From the BLS report:

From the BLS report:"The number of people employed part time for economic reasons, at 4.4 million, changed little in February. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been reduced or they were unable to find full-time jobs."The number of persons working part time for economic reasons decreased in February to 4.36 million from 4.42 million in February. This is slightly above pre-pandemic levels.

These workers are included in the alternate measure of labor underutilization (U-6) that increased to 7.3% from 7.2% in the previous month. This is down from the record high in April 2020 of 23.0% and up from the lowest level on record (seasonally adjusted) in December 2022 (6.5%). (This series started in 1994). This measure is above the 7.0% level in February 2020 (pre-pandemic).

Unemployed over 26 Weeks

This graph shows the number of workers unemployed for 27 weeks or more.

This graph shows the number of workers unemployed for 27 weeks or more. According to the BLS, there are 1.203 million workers who have been unemployed for more than 26 weeks and still want a job, down from 1.277 million the previous month.

This is close to pre-pandemic levels.

Job Streak

| Headline Jobs, Top 10 Streaks | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year Ended | Streak, Months | |

| 1 | 2019 | 100 |

| 2 | 1990 | 48 |

| 3 | 2007 | 46 |

| 4 | 1979 | 45 |

| 5 | 20241 | 38 |

| 6 tie | 1943 | 33 |

| 6 tie | 1986 | 33 |

| 6 tie | 2000 | 33 |

| 9 | 1967 | 29 |

| 10 | 1995 | 25 |

| 1Currrent Streak | ||

Summary:

The headline monthly jobs number was above consensus expectations; however, December and January payrolls were revised down by 167,000 combined. The participation rate was unchanged, the employment population ratio decreased, and the unemployment rate was increased to 3.9%. Another solid report.

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoAll Of The Elements Are In Place For An Economic Crisis Of Staggering Proportions

-

Uncategorized1 month ago

Uncategorized1 month agoCathie Wood sells a major tech stock (again)

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoCalifornia Counties Could Be Forced To Pay $300 Million To Cover COVID-Era Program

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoApparel Retailer Express Moving Toward Bankruptcy

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoIndustrial Production Decreased 0.1% in January

-

International3 hours ago

International3 hours agoWalmart launches clever answer to Target’s new membership program

-

Government1 month ago

Government1 month agoWar Delirium

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoRFK Jr: The Wuhan Cover-Up & The Rise Of The Biowarfare-Industrial Complex